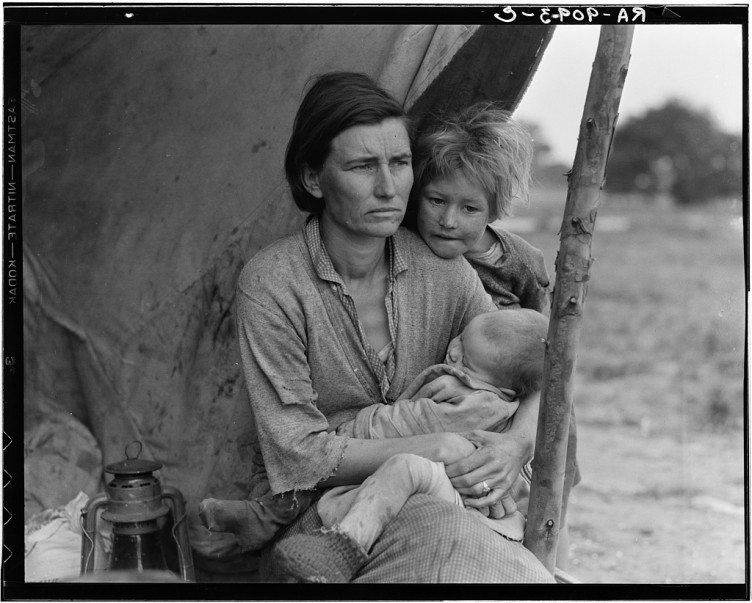

Something appears to have been mixed up here, since the photograph above is not the well-known Migrant Mother photograph by Dorothea Lange. However, it is, unmistakably, the mother from that photograph. What I’m going to do in the following is to try to investigate how portraiture works (at least in part) by using a set of Lange’s photographs, namely the Migrant Mother ones that can be found in the Library of Congress. (For this article, I’m using the scans from the LOC scans, hence the frames and the writing around the image) There are all kinds of reasons for me to pick these images, the most important ones being that everybody knows the most well-known picture, while only few people have ever seen the other ones. In fact most people don’t even seem to be aware of them. I’m going to ignore all background information about these photographs other than what is available in the LOC, since I want to discuss what can be seen in the photos.

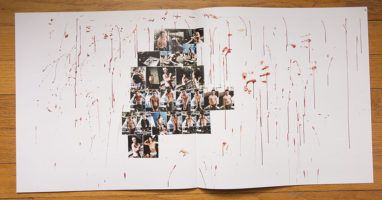

The photograph that everybody is so familiar with is this one:

What do we actually see here? First of all, there obviously is a woman (in the center of the frame) whose gaze does not meet the camera’s lens (and thus the viewer’s eyes). Her face appears worried, there is a bit of a frown in her face, and with her right hand she is holding or possibly slightly pinching the side of her face. Apart from the woman, there are three (yes, three) children visible. Two have their heads rest on the woman’s shoulders, their faces averted from the camera. The third child is a baby whose (sleeping) face is visible at the right edge of the frame, behind that wooden pillar.

For those who like to obsess over Photoshop manipulation “scandals”: The woman is actually holding on to that pillar with her left hand, and the lower right corner of the frame one can faintly see the retouched thumb (to see more images, including a restored one, see this page). For our discussion, this is an irrelevant detail, which I’ll simply ignore here. I’m also not going to touch upon the fact that the image is an iconic photograph. There are repercussions of that, but that’s for another day.

Back to the photograph, while the mother’s pose seems fairly natural, the two larger children’s has always struck me as a bit artificial. Children not familiar with a stranger might show their shyness, but these poses seem maybe a little bit too posed. And posed they are. Lange used a 4×5 view camera for these photographs, a camera that usually requires careful preparation of each photograph. Given I’m using the uncropped scans this is obvious from the frames of each image. But even if one didn’t know that, subconsciously most people I have talked to about this photograph tend to pick up on the posing aspect. Since most portraits are posed there is very little one could infer from the device itself, so beyond noting that I’ve always found the children’s poses a tad contrived I’m not going to add anything else here.

But obviously given we are not dealing with a candid photograph, the subjects were fully aware of the presence of the photographer. In fact, the photographer made them pose – this claim might not convince some people, yet, but once we’ve seen all the other photographs it will be obvious.

Given what we see in the photograph, it seems safe to assume that the children are in fact the woman’s, even though we can’t know for sure. Photographs often contain surprisingly little actual information, yet common sense allows us to come to fairly simple and usually correct conclusions. We know that this photograph is known as Migrant Mother, so assuming that these are in fact not the woman’s children would appear to be quite the stretch.

Here is the full caption of the photograph: “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California” (note that the main page gives “Destitute peapickers in California; a 32 year old mother of seven children. February 1936.”). Knowing the full caption adds a bit of information that is not actually contained in the photograph. Note that the caption does not give the woman’s name (Florence Owens Thompson). For a start, she looks as if she were significantly older than thirty-two. Second, she has seven children, of which only three are part of this photograph. Where are the other ones? We don’t know. But we might start coming up with theories or ideas. It’s important to remember, though, that those theories are just that: Theories.

When looking at photographs, all we have is what is contained inside their frames, plus, possibly, whatever additional information the captions might provide. If we think we know something about a photograph that is not visible in the frame and that is not mentioned in the caption, then it’s not unlikely we have come to a conclusion that is not supported by the photographic facts. When looking at photographs the very first thing is to become aware of what we see – and what we think we see.

Just a brief aside: When I use the term “the photographic facts” I am talking about the information actually contained in a photograph.

Back then to the picture from the very top:

It’s the same woman, plus two of her children. One of them, the one on the left in the famous frame, is gone. The baby is still there, and it is more clearly visible now. The other child – we can identify the hair and the rather ragged, coarse clothing – now rests her head on her mother’s shoulder. As before, both mother and child look away from the camera (the baby is sleeping).

This photograph is framed differently. It’s a horizontal framing, not nearly as close as the previous one. Comparing the way these two images were framed is instructive since it tells us something about both photographs. The original photograph is framed very tightly around the mother who provides a visual anchor (note I’m calling it “the original” since I used it to start this discussion; here and in the following I’ll refer to the images in order in which I discuss them in this article). She supports her children, literally (we are led to believe) and pictorially (they rest their heads on her shoulders). In contrast, while she still is at the center of the second frame, everything seems looser. Two thirds of the frame are occupied by very little – on the left a lamp in the foreground plus a tarp in the background, and on the right a post that holds up the tarp plus an out-of-focus background.

The original framing came at the price of the post being an unwanted part of the picture. This might be the reason why Lange retouched the image, to remove the thumb: The photograph was going to be grounded on the mother, and the mother holding on to something would divert from that photographic device. In the wider, horizontal photograph, the environment plays a much larger role now: It is mostly barren, empty, impoverished (mind you, I’m only talking about the environment that is actually visible in the photograph).

Also note how the woman’s left hand is visible in the second frame. She is wearing what might be a wedding band or engagement ring. This is the hand that is not visible in the famous frame. I have no way of knowing whether Lange intended to hint at this or not, but the ring adds a little piece of information about the woman, which, in turn, might trigger additional conclusions. If there is in fact a man in her life – these children must have a father – where is he? The famous frame, with the left hand invisible (remember, the thumb even got retouched out of the frame), omit this fact and makes the photograph center on motherhood alone: The mother as the anchor, providing the strength the children rely on (again literally and in terms of how they’re posed). The second frame, on contrast, could be read as a wife who is supporting her children but who also is waiting for her husband or partner to come back, to bring back food or money or whatever else.

As before, one needs to be careful about the photographic facts and whatever one might want to infer from that. The ring on the woman’s hand is a photographic fact. Everything else is an assumption.

Here’s the caption of the wider shot: “Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven hungry children. Mother aged thirty-two. Father is a native Californian. Destitute in pea picker’s camp, Nipomo, California, because of the failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tent in order to buy food. Of the twenty-five hundred people in this camp most of them were destitute”. That is a lot more information than before. As before, this information gets our minds going, yet we need to be very careful with what conclusions are going to be ours, and which ones are actually supported by the photograph.

Let’s keep looking. Here’s another frame:

This third frame is close to the second one in terms of the poses. Very little has changed – the older child is now holding on to the post, and the heads have moved a little, possibly to accommodate the different camera position. This frame was shot vertically, and it reduces the little family to an even smaller part of the image, still in the very center, though. There is what looks like a suitcase or trunk in the foreground, somewhat out of focus, upon which a plate rests. There is the lamp again, as are the tarp, the post, the empty backgrounds. Part of the ground is now contained in the frame, in the lower right corner it is in focus: It looks like sand, some sort of soil.

The third frame differs quite a bit from the first, famous one. While I’m happy to argue that the poses look much more natural, the intense focus on the mother is almost completely gone. While she still occupies the center of the frame, the somewhat active pose of the older child has both of them battle for the viewer’s attention. And the group looks almost lost in these desperately poor circumstances – a tent of sorts held up by a post made from a young tree, a single plate, a suitcase (or trunk) as a table.

We might as well step back even further:

Now this is a very different picture than the “original” Migrant Mother, isn’t it? For a start, the mother is not even in focus/the focal point of the picture. Instead, it’s a child sitting in a rocking chair, in front of a makeshift tent. Inside the tent, we can see the mother (holding the baby), plus two other children, both of them younger than the one in the chair, both probably the children from the other frames.

Interestingly, this is the only frame where the subjects are actually engaging with or at least looking at the camera. Most of the posing efforts seem to have been spent on the child in the rocking chair, while the group in the background (in the tent) essentially just make sure they occupy the correct spot in the frame.

Note how this image is constructed photographically. The opening of the shelter provides a photographic frame. The subjects are all placed inside that frame, the group in the background very obviously so (they are in fact inside the shelter), whereas the rocking chair (plus an open suitcase) have been placed in front of the opening of the shelter. They might have been there when the photographer arrived, we can’t know for sure. But visually, there are two worlds: The one of the family, in the center, photographed inside that frame, and the larger world outside, a fairly uninviting, empty place.

Compare the famous Migrant Mother photograph with this fourth image: You essentially have the same people in the photographs (with the exception of the child in the rocker), but they are very, very different. And all of that from working with the distance between the camera and the subjects (and some careful arranging of the frames at each distance). I have no way of knowing which frame actually came first; I want to assume Lange started further away and then moved in, but it could have been the other way around. From the photographs, it’s essentially impossible to tell (and it frankly doesn’t matter anyway).

There is another photograph:

Photographed at a distance roughly between the second and third frame, it shows the mother in the very center of the frame, breastfeeding her baby. Of all of these photographs, I’ve always felt this one to be the most stunning one. Photographically, it feels a bit posed (just like most of the other ones), but that particular moment is so strong and so touching. The mother’s expression, which looks like weary resignation, creates a strong contrast to what she is doing: Feeding her baby. None of the other children are contained in the frame, this one is focused just on a mother nursing her baby.

The photograph that became the iconic Migrant Mother is the one where the camera is closest to Florence Owens Thompson. Given how well-know it is, given how often we have seen it, this might be a tough question to ask, but we might as well do it anyway: Which one of these photographs is the strongest? Personal preference (plus agenda and biases) might have us pick one over the others, but is it going to be the famous one? Is it even going to be possible to disentangle all we know and feel from these photographs?

If we ignore the fact that one of these frames has become iconic, the variety of the photographs – the way they are composed, their distance to the subjects, etc. – gives us an opportunity to see how portraiture operates, how adding or withholding information can contribute to the way a portrait is perceived, how adding or withholding information makes us see and then feel different things.

Of course, there is nothing fundamentally revealing about any of this – it’s photography, after all, and this is what photography does. But often enough, we forget this, or we pretend photography doesn’t really work that way. When talking about photographs, it’s essential to start out from the facts, from what is contained in the frame, from how things are set up, and to then move to whatever one might infer from that.

I often find that people approach photography the other way around, by bringing their own conclusions to the images, to then try to see how the photograph supports them. I don’t think that’s a good approach. With so many photographs around us now, in all likelihood what is going to happen is that instead of us navigating photographs, we are instead being led. Instead of being active, we end up being passive. That can’t be good. How can one make choices if one doesn’t have the tools at one’s disposal that are needed to make these choices?

Portraiture makes the viewer’s task particularly tricky, because it often seduces us to see things that aren’t actually there. A photograph of another person never is that other person. It always “only” is a photograph, made with specific devices and (usually) intent. To understand how portraiture works, one needs to look at the use of the devices, to possibly infer a little about the intent, and to learn a lot about what we bring to the table when looking at a photograph of another person.

Update (22 May 2013): A reader emailed me to say the photographs were taken with a press camera, not a view camera. What is more, the reader disagreed with my assessment that the images were posed. While part of that discussion comes down to semantics, the main idea of this article is not based on whether or not these images were posed. I’m concerned with what we can infer from the pictures, to be precise from trying to rely only on the photographic facts. Obviously, my assumptions and conclusions might differ from yours.

This article is the first in a series, engaging with portraits to see how they work and what they say.