In early 2021, I spoke Karolina Gembara about her work (you can find the long conversation split up into part 1 and part 2). There was one particular aspect of the conversation that I kept coming back to in my head (it’s from part 2): “Recently I completed another project where photography is only a pretext. During the Nowi warszawiacy workshop one girl mentioned her family struggles with finding a flat — landlords reject them because they are refugees. So I dedicated my time to become an agent to find housing. […] The whole process was recorded on video, with images and audio. […] The visual part is just a documentation. The most important part is that the family found a flat. The visual layer is present, but the core of this project isn’t visible in a traditional way.” (my emphasis)

It was the conclusion of this description, the part that I emphasized, that made me think. I remember how initially, I lost interest in the project, given that it wasn’t about pictures (or visuals). But with time, I started to challenge my own assumptions, in particular once I started looking into the two books that ultimately resulted in my recent article about photographers and their idea of collaboration. Am I too attached to what Karolina called “the traditional way,” namely the idea that at the end of a photography project, the pictures ought to exist on a wall (possibly framed) or in a photobook?

Don’t get me wrong, I absolutely love looking at prints on a wall or in a photobook. But this particular format has its limitations. To begin with, its audience is limited. It often excludes the very people who would find themselves in the pictures. Furthermore, as I’ve argued in my article about collaboration, in the end, the real problem to be solved tends to be a photography world one — unlike in the case of Karolina Gembara’s project where the “most important part [was] that the family found a flat.”

“The art world has never known what to do with Wendy Ewald.” Abigail Winogrand writes in her essay that’s included in The Devil Is Leaving His Cave (p. 114) “Indeed, it has frequently underestimated her. […] her work remains difficult to categorize, particularly in a market and institutional landscape still defined, financially and otherwise, by the heroic notion of the singular artistic genius.” In what follows, Winogrand nevertheless attempts to place Ewald into an artistic context. On the one hand, that’s a worthwhile endeavour: how can we understand an artist when they’re completely detached from everybody else?

On the other hand, maybe resisting the impulse might be the bolder move. After all, as the history of art has already shown, there exist artists who push what we understand as art and/or what art can do in a singular, determined fashion. Maybe we can understand Wendy Ewald this way? Especially photo and art historians might be most resistant to such a push — it’s difficult to write art history by ditching parts of one’s own frame work.

But for the rest of us, I do believe that there is ample food for thought here. After all, why should the work produced by this particular artist be made to conform to parameters that aren’t very well suited for it when doing the complete opposite — expanding the parameters — might not only lead us to a better understanding of it, possibly leading to a better way to recognize the strength of her work, but also to a collective re-understanding of what photographs can do?

Maybe this should be our task, especially when we deal with the idea of collaboration in photography: instead of having the world conform to our conventions, we might want to explore a widening of the conventions so that there is more space for the world — and, consequently, a widening of the possibilities of photography itself.

But no, photography itself does not need a widening of its possibilities. It already is very wide. Instead, it’s how we see and treat photography within confines of the art world where the narrowing is happening.

The Devil Is Leaving His Cave makes this clear. The book contains two separate bodies of work (if that’s even the right word) that are interrelated. In 1991, Ewald went to Chiapas, the southernmost province of Mexico, to lead photography classes with a number of children from local communities. Roughly three decades later, the artist worked with fifteen young Mexican Americans living in Chicago. The later part entailed a number of differences: photographic materials had changed, and there also was the (at the time of this writing ongoing) Covid-19 pandemic that required some remote teaching.

In terms of their approach, there are some differences as well. The children living in southern Mexico set out to produce a record of their daily lives that, crucially, also entailed staging photographs of dreams. This is where the book’s title originates: it’s the caption (“description”) of the picture on the cover (that can also be found inside the book). “For the Maya students,” Ewald writes in her introduction (p. 15), “dreams played as important a role in understanding the world as waking events”.

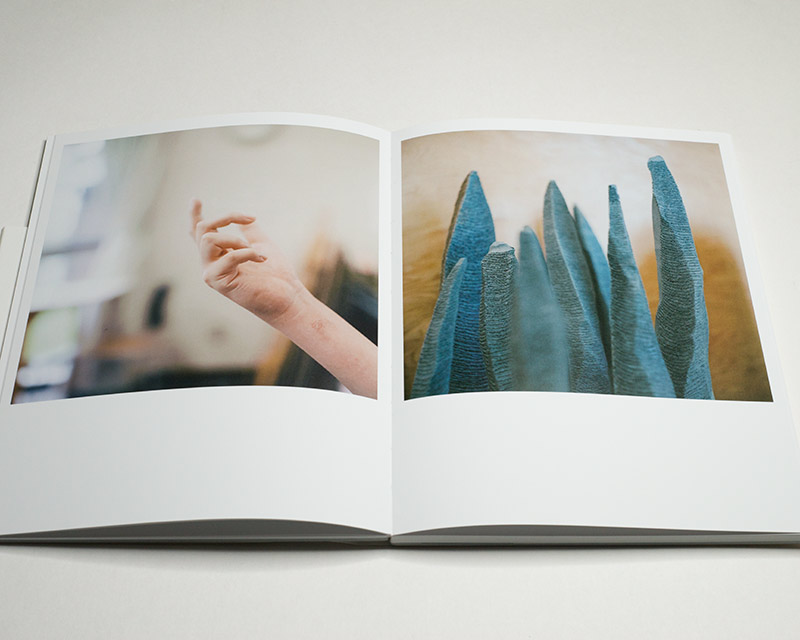

Photographically, the photographs are incredible. But they defy easy categorizations. How do straight up documentations sit next to depictions of dreams that derive their visual power in part from their own technical crudeness? Well, they do, especially if you accept the approach the Maya students would have taken: all of the photographs speak of the same thing — their lived reality.

The later workshop produced text heavier outcomes, possibly in part because its participants were a little older. Here, the concern with the aspect of immigration comes into sharp focus. “When you’re little,” workshop participant Marestela Martinez writes (p. 108), ” it’s not so hard being Mexican and American because you’re still growing. You don’t understand what people are saying. You think they’re talking just to you. But now it’s hard, because you understand.”

Next to Marestela Martinez’s large portrait and right above her testimony, there’s a photograph she took of a mural showing George Floyd. Around his head, she wrote the following text: “His daughter will grow up and see her dad’s last moments everywhere”. It’s too awful a sentiment to consider even as of course, this is exactly what’s going to happen. And it’s equally incredibly touching to see the young Mexican immigrant sympathize with George Floyd’s daughter.

At the end of the day, I don’t think that photographers have to change anything if they want to pursue their idea of collaboration. There’s nothing wrong with producing something made for and seen only by people in the world of photography. At the same time, in light of the explosion of crises we are facing right now and in light of our own governments’ reluctance to provide even a modicum of a solution for any one of them, this approach increasingly reflects the luxury position that being an artist entails.

It is work such as Wendy Ewald’s The Devil Is Leaving His Cave that has the power to point toward possibly more interactive approaches in photography where a collaboration ends up being a give and take. Ultimately, at least some of the ideas we cherish in the world of photography might have to be diluted, if not expanded (where not abandoned).

In the end, this can only lead to the world of professional photography becoming richer, as it soaks up some of the ideas that people who don’t consider themselves photographers have taken for granted for a long time. At the same time, professional photographers and artists do possess skills that have the potential to enrich the contributions made by those we ask for a collaboration.

Recommended.

The Devil Is Leaving His Cave; photographs by a number of contributors including Wendy Ewald; essays by Wendy Ewald, Abigail Winogrand, Edgar Garcia; 144 pages; MACK; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!