Looking through Rinko Kawauchi‘s as it is, I couldn’t help but think that all of her previous work was merely a preparation for this, a book about the birth and first years of her daughter. It’s not an experience I am familiar with from my own life, but I have always imagined the birth of one’s child to be the biggest of all small miracles. This book showed me that indeed it is. It’s filled to the brim with deeply touching photographs of Kawauchi discovering a plethora of beauty in her young daughter’s discovery of the world.

For me, this artist has always shone the brightest when she used her camera to capture the world’s small miracles. That said, as much as I enjoy the earlier work (such as, say, うたたね [Utatane]), those pictures now feel cluttered compared with the incredibly reduced and deeply concentrated photographs in as it is. I could speculate whether this is due to the subject matter or the increased maturity of the artist. But such speculation would feel mostly besides the point here.

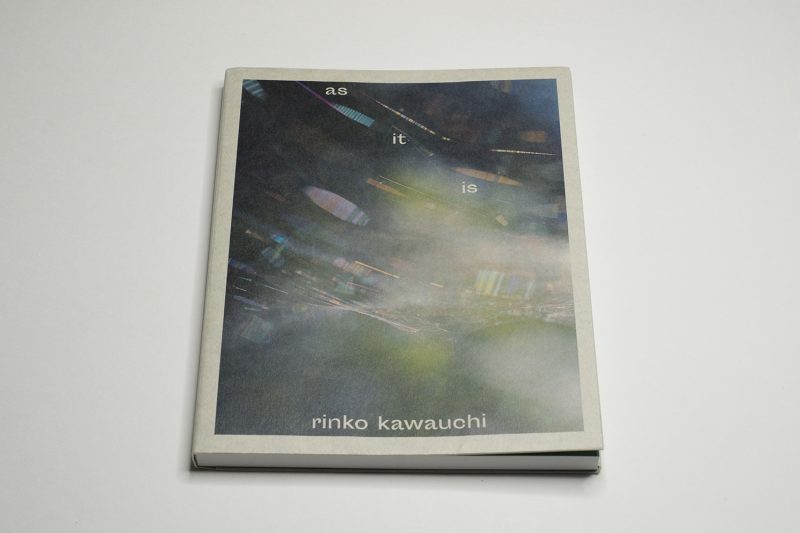

I should note that this new book thankfully follows the model of the earliest books. It’s a very nicely understated softcover book, avoiding the unnecessary pomposity with which Western publishers have treated Kawauchi’s photography too often. A coproduction between France’s Chose Commune and Japan’s torch press, the book was designed and printed in Japan, and it has the form that the photographs and subject matter ask for. This is crucial.

Photographed between 2016 and 2020, the book follows a chronological approach. The baby is born, and we witness her slowly get older. Initially being in the gentle and caring hands of those closest to her, more and more she begins to be her own little person, becoming aware of the world around her. You can see her eyes beginning to focus. While it’s impossible to know what’s going on in her mind, as viewers we can imagine: this must be the easier time from childhood that often we yearn to be able to get back to.

Kawauchi has often worked with pairings of photographs. If in the past I had any misgiving about that, it’s that often, the pairings were too simplistic, too on the nose: this looks like that. Here, the pairings are much more relaxed. They feel less self conscious. Often, they’re metaphorical, which helps to bring out the added value that can be had when two pictures are being paired.

As I already noted, the photographs also feel more reduced. It’s tempting to connect this to Japan’s embrace of simplicity and minimalism. In actuality, that embrace is more complicated than the often superficial caricature it is presented as in the West. If anything, that embrace is a mind set more than anything else. I sense it behind these photographs: the more you focus your attention on one thing, the more of the world falls aways. At the same time, the world reveals itself anew.

The soft whisper of what is left becomes clearly audible. Here, a plant’s seed caught in the young girl’s hair at the back of her head suddenly means so much, and the bud of a flower is almost too much to bear. There’s a bright green, young plant against a black background, there’s a little frog clinging to a window covered with rain drops.

The book contains a few inserts with words written by the artist. In the copy of the book I bought they’re in English and French. By chance, I discovered that the voice employed in the English and French texts is rather different. This has me wonder which one is closer to the Japanese original. But that might just be an impossible question to ask, given the differences between Japanese and English/French.

In essence, the words substitute pictures that could never be taken, and they expand what is on view in the photographs. In some of her earlier books, Kawauchi had already used text, and I’m glad that she decided to do it again.

Here I am, at the end of a year that for obvious reasons will be remembered well, yet not fondly. Two of the three photobooks that deeply affected me were made by two very different Japanese women photographers (the other one is Yurie Nagashima). As a childless middle-aged Western man I don’t share their life experiences. But through their sharing of their life experiences in the form of two photobooks, I was able to gain access to something formerly inaccessible to me.

What I gained access to was not only something they experienced and put into pictures. In addition, I was also made to look at my own life more closely, using different angles than the ones I had been so familiar with.

I can’t know this for a fact, but I think that you could have a baby and unlike Rinko Kawauchi you’d still not be aware of the world’s wonders. Hers is not only a book about having a child. I see it first and foremost as a book about what happens when you open yourself up to the world and let some more of its beauty in, a beauty that is available to all, regardless of whether you capture it in pictures or not.

This is not to deny the ugly truth of the world that has been exposed to us this year — in particular in the US, where the pandemic has revealed the systemic cruelty in the country’s very heart, its very eagerness to disregard people’s suffering and death.

Without us being able to see an alternative (an alternative that’s no just slogans that might win or lose an election), we are not going to get anywhere. Part of that alternative will have to be an open embrace of beauty. It is the arts that can show us what that might mean.

This book, as it is, is what we needed this year. It is a miracle itself.

Highly recommended.

as it is; photographs and text by Rinko Kawauchi; 144 pages (plus inserts); Chose Commune/torch press; 2020

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 4.8

Ratings explained here.