I would love to believe that it is our intentions that determine the outcome of what we produce. In some ways, they do — if, and only if, we manage to have the outcome of our work reflect those intentions. That, however, is not a given. Often, it’s not the case.

As a viewer, how would I know about a photographer’s intentions when I only have their work? How, that is, if s/he didn’t explicitly provide a list of intentions? In the absence of such a list, I can only try to infer the intentions from the work. I might or might not be successful. Thus, I have maintained for a long time that discussions of a body of work that center on a photographer’s intentions are not very fruitful.

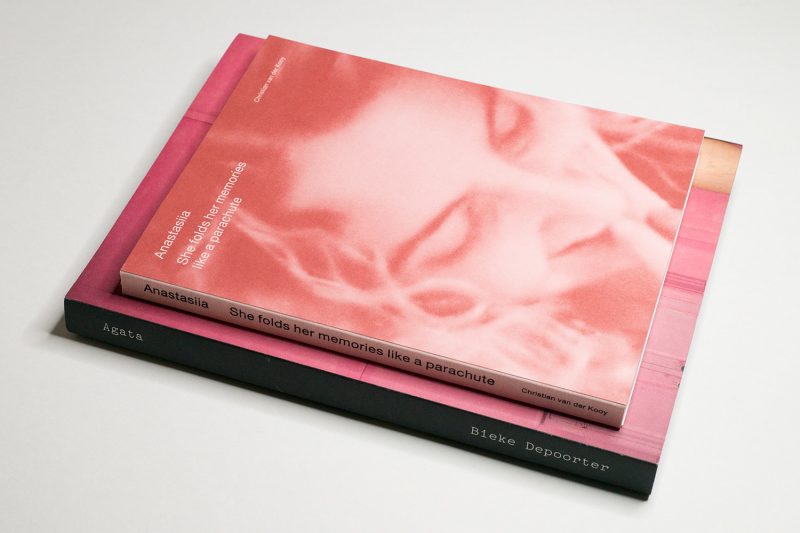

With that in mind I want to consider two recent photobooks: Agata by Bieke Depoorter (self-published in 2021, of which I own a copy of the second printing) and Anastasiia: She folds her memories like a parachute by Christian van der Kooy (published by The Eriskay Connection in 2018). Both books centre on the same idea, namely that the interaction between a photographer and her or his subject (another person) is considerably more complex than the traditional model of the privileged storyteller telling someone else’s story. Both books attempt to solve the problem by incorporating the subject’s voice, by giving her an opportunity to speak for herself.

We might note that both books contain a degree of fiction, the full amount of which is unknown to anyone other than their makers and, possibly, their subjects. I should note that I view the word “fiction” in a neutral manner. A fiction might arise from any number of fictional events, places, or people just as much as from omissions and other decisions made while producing a body of work.

In the strictest sense, all photographs are fictions, given their photographers’ choices. But in a number of circumstances, we can ignore this fact (even if this might decision might run the risk of falling for the very fiction whose presence we’re ignoring). In the case of these two books, there might be ample fiction. We don’t know the full extent of it. We’re well advised to keep this in the backs of heads.

I’ve read what has been written about the books. Still, it’s always a bad idea to trust photographers and photobook makers too much: trust what they’ve made, but don’t believe their spiels.

While the overall stories behind Agata and Anastasiia are different, the two books have a number of things in common (in the following, when the names are written in italics, they refer to the book). In both cases, their basis is a relationship between two people who started out as strangers. Agata Kay and Bieke Depoorter met as subject and photographer and ended up being friends, even as the extent and full character of the friendship is not fully revealed. Anastasiia (no last name given) and Christian van der Kooy met as fixer and photographer and became lovers. In both cases, the books contain an extensive amount of photographs of Agata and Anastasiia, plus their own words.

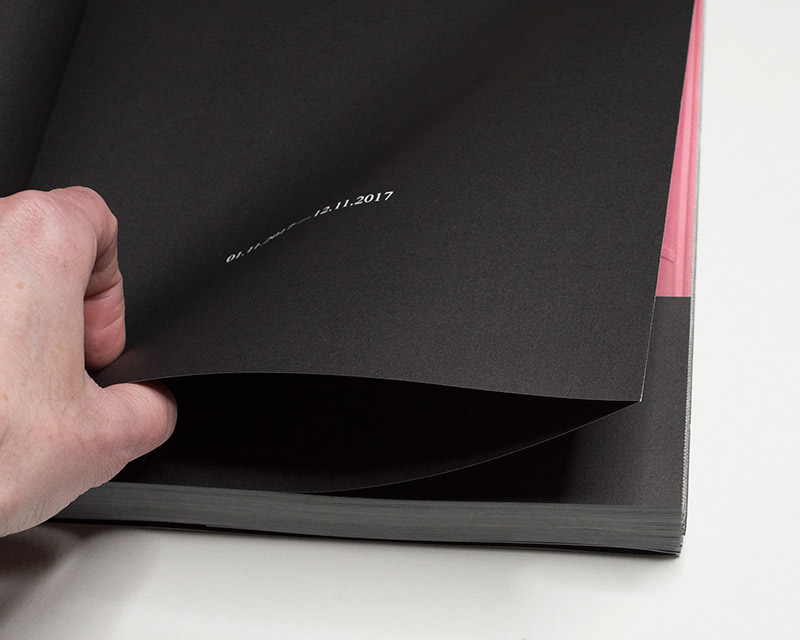

There are different production strategies employed to convey the stories in Agata and Anastasiia. The latter uses graphic-design elements to show the difference between the photographer’s and his subject’s words. They are reproduced in black and magenta, respectively. In the case of Agata, most of the young woman’s words is shown as handwritten text. The bulk of it is initially hidden inside the folds of pouch pages (this is a type of binding commonly used in traditional Asian books): a viewer/reader has to cut the (perforated) fore edge to get access to their interior, which either contains text or photographs (or occasionally simply blank pages).

Conceptually, this is a nifty game that I have seen being played in other books. Given the perforation, though, it doesn’t feel as if my — the viewer’s stakes — are quite as high as they could be. After all, the pages will come apart easily. The perforation makes me think of a zipper. Opening up the pages feels a lot less consequential than in the case where I would have had to use a knife.

There is the old belief, now mostly discarded, that a camera can steal one’s soul. This idea now strikes us as naif, even if, I maintain, some photographers are aware of the fact that something like that can actually happen. In an extreme case, a camera can become a weapon. At the very least, writing someone else’s story with a camera takes away that person’s agency.

What we thus ought to be talking about is that it’s the photographer, not the camera, who is doing the stealing. Let’s keep this in mind.

(continued…)

The full article is only available for subscribers of my Patreon. Please consider signing up for a subscription. In addition to getting access to this piece the existing Patreon archive will become accessible (articles and photobook videos).

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!