It’s far too early to summarize what exactly went wrong with the war in Afghanistan (assuming that that’s even a good approach to the issue). However, it’s not too early to note that the media played a huge role in the war. In his newsletter, Judd Legum called out what he termed The media’s systemic failure on Afghanistan. You will want to read the piece.

If you’re curious what the US government really knew about the situation on the ground, read What We Need to Learn: Lessons From Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction (links to a pdf). This is the 11th report the agency wrote, and you can understand the events of the past weeks a lot more easily.

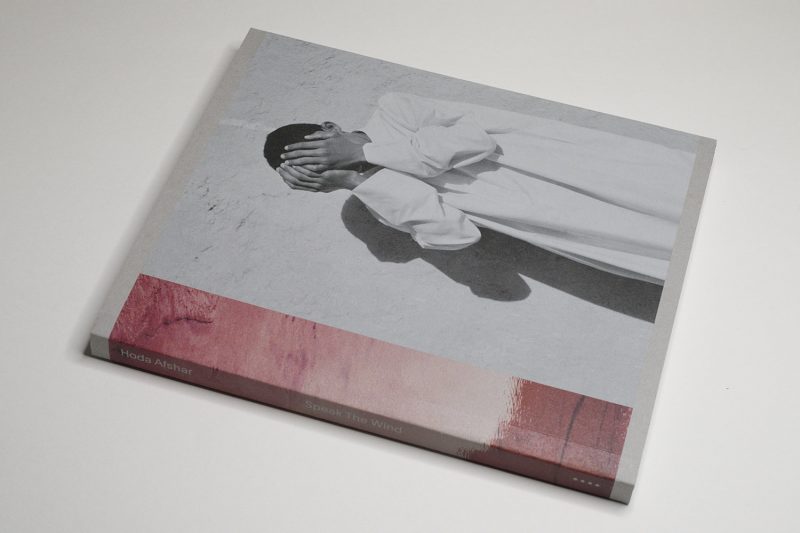

It’s not clear, yet, whether the end of the war will trigger discussions about the role photography has played to communicate its course or meaning. These kinds of discussions aren’t new, yet they deserve to be re-visited in light of the past twenty years.

In fact, war photography can look back to a history that’s long enough for it to have spawned its own secondary literature. We have basically known that it doesn’t work for quite some time.

The photographers who go out to photograph wars know that the actual experience of being in a war zone cannot be communicated with pictures. The people who look at photographs of war now know very well that war photography also doesn’t do much for or to them. It’s debatable to what extent war photographs have shaped the public discourse.

Some of the finest photojournalists and photographers went to Afghanistan and risked their lives to take pictures, only for us, as viewers essentially knowing barely more about the country, its people, and the war than 20 years ago. I don’t see this as a photography failure because the pictures these men and women brought home never existed in a vacuum. They became embedded in the media whose corporations commissioned them.

“The single biggest mistake that a photographer can make,” Philip Jones Griffiths once said, “is to believe in the profession, to believe in magazines and newspapers. When that happens, you have already failed. One must work first and foremost to satisfy oneself.” (quoted from: Interview with Philip Jones Griffiths, by Geert van Kesteren, Brigitte Lardinois, and Julian Stallabrass, in Memories of Fire: Images of War and The War of Images, ed. Julian Stallabrass, Photoworks, 2013, p. 68)

The main point I will make in the following boils down to this: while the media have largely failed to provide a meaningful picture of the so-called War on Terror (in part because of their own complicity in it), independent efforts by a number of people (photographers, critics, artists) have resulted in a number of books that managed to achieve two things. First, they each advanced the form of the war photobook a lot further. Second, they each embraced a paradigm shift that centered the voices of those taking (or using) the pictures. The second aspect will become more clear in the following.

In parallel to twenty years of war, another reality has emerged that in the West is slowly, yet steadily being accepted by more and more people: Western photojournalists can only speak with authority about their own countries and cultures — unless they embed themselves with local communities for a long time, picking up the language etc.

Such an approach runs counter the dominant parachute-in approach still used by most photojournalists. What’s more, it can’t be the presumed task of a Western photojournalist to speak about other people’s experiences — when those people are fully capable of doing it themselves (there are, after all, non-Western photojournalists, right?).

This fact aligns with the second of my observations of today’s cutting-edge war photobooks: those who take (or use) the pictures are being centered. This takes on a variety of forms.

Maybe the most pronounced aspect is that photojournalists from countries that waged the wars have put their own countries front and center. To some extent, this already happened during the Vietnam War. But it now has become vastly amplified, as visual propaganda is openly critiqued.

War photobooks now contain pictures taken far away from where the bombs are falling: there are pictures of ordinary citizens going about their business, and, of course, soldiers coming home from the war, often heavily physically and mentally scarred, are being shown in the midst of a society that can’t understand what it did to them (it’s worthwhile to note that the latter is a recent addition in the world of photography; the world of literature is filled with examples that are a lot older).

The change was driven by a small number of people who believed in themselves and their mission, working with the likes of The New York Times where necessary but ultimately shaping their own message: war photography’s real goal is not to pretend that violence happening far away can be objectively displayed. Instead, the goal is to dive deeply into the heart of our own involvement in the mayhem.

Here, I want to single out a few books that I feel have each not only pushed the conversation about the war photobook a lot further, but that also have provided unprecedented insight into the past twenty years. Where I reviewed the books on this site in the past, I will link to the article. I should say that I have not re-read these articles. It’s possible that parts of my thinking might have changed or evolved. But I am pretty certain that my main view of the books’ merit hasn’t changed.

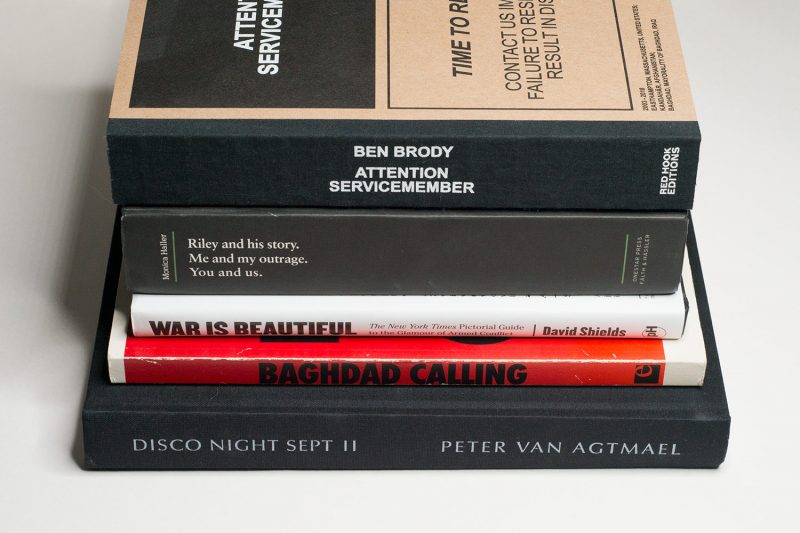

David Shields’ War Is Beautiful is subtitled “The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict” (reviewed here). For the book, Shields selected photographs that had been featured prominently on the front page of the newspaper (that had played a critical role in selling the invasion of Iraq — it later issued an apology of sorts). He then sorted the photographs into a number of categories that were based on larger ideas expressed through them.

In spirit, the book operates along the lines of Roland Barthes’ Mythologies. The argument basically is that the photo editors of the newspaper select photographs to conform with specific ideas that center on their underlying US ideology. Even if I would have organized the material differently, the basic idea is very solid, and it provides considerable insight into the uses of photography on the cover of the most prominent US newspaper.

Shields’ book is important because it is intended to trigger a critical dialogue about the uses of pictures and how these uses often reflect an ideology more than what’s actually on view in them (if you’ve read my book Photography’s Neoliberal Realism you know I’m using a similar approach there). But it indirectly also makes us gaze into what historically has been an area of contention, namely newspaper editors working with pictures in a way that possibly is in conflict with the photographers’ original ideas.

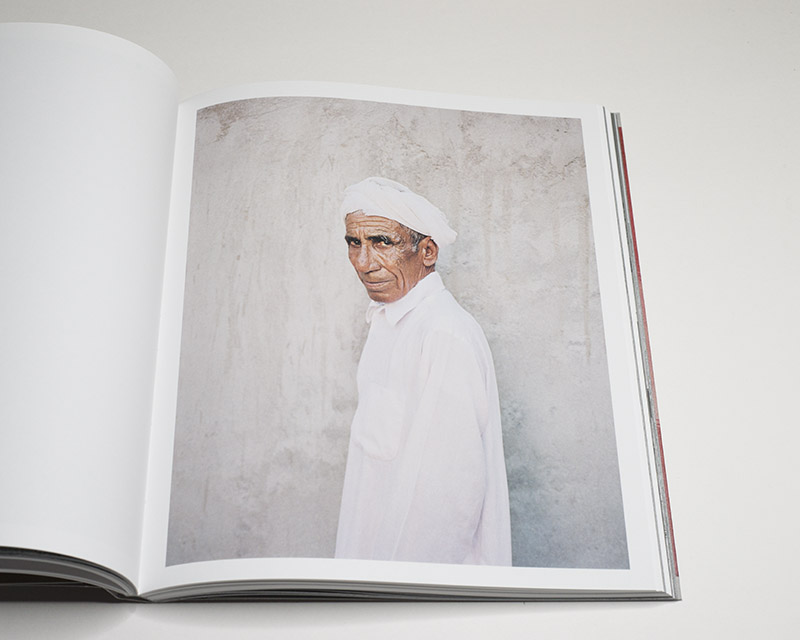

Geert van Kesteren’s Baghdad Calling unfortunately has now become one of those out-of-print rare books (review here). Much like War Is Beautiful, it attacks the conventions of photojournalism. The book features a very large number of photographs taken by Iraqi citizens that had been forced from the country during the worst of the violence there. In addition, their voices are given: the photographs feature descriptions of what’s on view in the photographs.

The book’s brilliance lies in the fact that it’s Iraqis telling their stories through their own pictures. Van Kesteren added a few of his own photographs, depicting the Iraqi refugees in their temporary homes in neighbouring countries. It’s an incredibly effective book that shows the power of photography, especially when it’s used for purposes that we now see on social media.

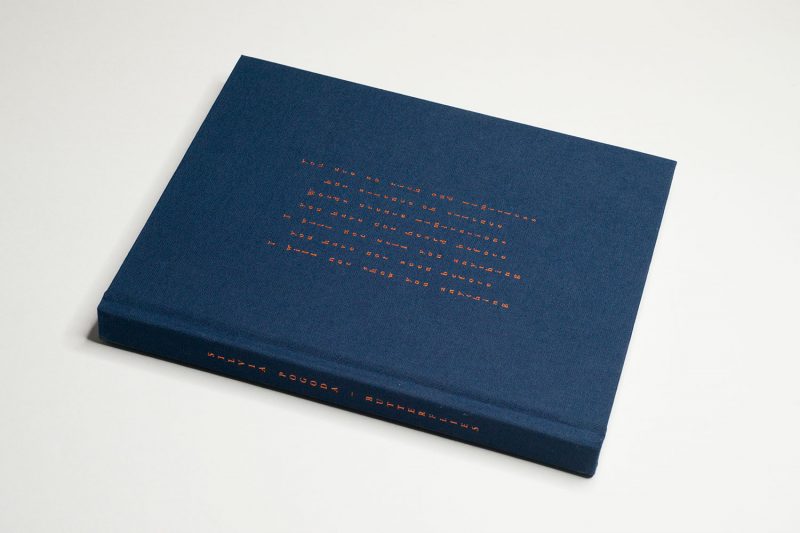

Monica Haller‘s Riley and his story operates in essentially the same way as Baghdad Calling. Here, though, it is a large selection of photographs taken by a friend of Haller’s who served as a nurse at the infamous Abu Ghraib prison.

At nearly 500 pages, the book features an onslaught of photographs and text, exposing the daily life of any one of the many “foot soldiers” caught in the war’s huge meat grinder. The sheer repetitiveness of the imagery is mind numbing: certain scenes just repeat over and over and over again.

Riley asks much of the viewer/reader. But then, if there is any expectation on their part to understand more about war and what it might mean, I think inevitably, a book will have to expect much. Our understanding cannot be had cheaply, on the go.

Much like Haller’s friend, Ben Brody was a soldier in the US army. Unlike Riley, Ben was an army photographer, though, and he later became a photojournalist to go back to the war zones repeatedly (full disclosure: Ben is a former student and now friend of mine). These facts make his work interesting: he has seen the machinery of war first from within and then from without, a type of knowledge that many photojournalist don’t have.

Attention Servicemember dives deep into many aspects of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, some of which a viewer might be familiar with from regular photojournalism, but much which had eluded war photobooks until this one came along (reviewed here). Ben’s writing in the book is one of the most effective pieces of text I’ve ever come across in a war photobook — the book is required reading even just for that.

With the book, Ben blows huge holes into the standard narrative of the so-called War on Terror. It always was a farce more than anything, a farce that unfortunately cost way too many lives that shouldn’t have been lost.

Much like Ben Brody, Peter van Agtmael went to document the war as a very young man. But unlike Ben, he stayed on the outside, becoming a photojournalist.

If any photojournalist has produced the photojournalistic photobook about the wars, it’s Van Agtmael. In fact, there are two books, which are equally brilliant. There’s Disco Night Sept 11 (2014; reviewed here — trigger warning: some people might find the article’s main image — part of the book — upsetting), and there’s Sorry For The War (2021; reviewed here).

Both books feature a lot of photographs from the war zones. In both books, Van Agtmael also describes what people used to call “the home front”: scarred veterans are going home, government officials are trying to sell the war, popular culture arranges itself around an increasingly militarized society. Disco Night is closer in spirit to the classic photojournalistic book. With Sorry, the viewer encounters a photographer and citizen who is in deep despair over the ongoing folly.

I’m not going to argue that any one of these books is more essential than all the other ones. Ideally, a full set would be present in every US household so that people could see the reality of the war they paid for with their tax dollars and possibly voted for (let’s remember that in the Congress there was exactly one person, Representative Barbara Lee, who voted against the war in Afghanistan).

Of course, that idea is elusive and unrealistic. My main point here is not that more people should see these books — they should; but it’s their decision. Instead, here I wanted to stress two facts. First, the war photobook has evolved enormously over the past 20 years. This is due to the efforts of people who either were outsiders or who decided to ditch the conventions of their profession (photojournalism), to try to get closer to an understanding of these wars.

Second, in their own ways, they all realized that looking at their own underlying ideology needed to be part of that endeavour. They also realized that by construction, the standard model of photojournalism is incapable of doing what it pretends to be doing, because of its insistence on its own otherness, its own not being/becoming involved.

I suspect that there will be other books coming out about the wars. But it’s pretty amazing that we already have seen so many excellent war photobooks that cover the US-led wars over the past 20 years.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.