“As a white, Northern European photographer who had spent almost ten years of his active career in the warzones of this world,” Andreas Herzau writes, “I had a tendency to seek out the problems: casualties of war, mass graves, the damage caused by the fighting, and of course poverty. Under the guise of the well-intentioned humanitarian aim to inform and explain, we photographers travel through countries like Liberia reporting mostly on matters which are already well-known.” These sentences describe one of the main problems of photojournalism. It is heartening to see it expressed not by a critic or writer, or by someone who found themselves in front of a photojournalist’s lens, but by someone behind the camera.

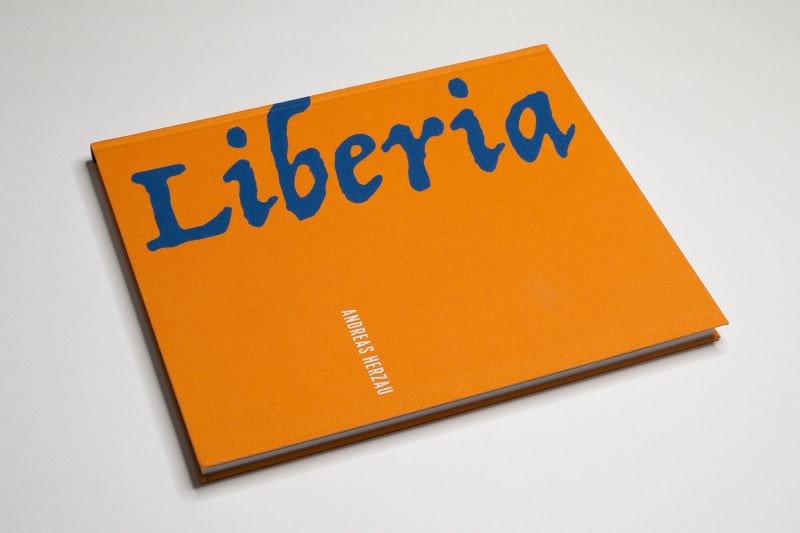

Some of the photographs Herzau took in the country in 1996 during its civil war are included in Liberia (the book; in the following, the italicized word refers to the book, the regular form to the country). About two thirds into the book, there is a section of pages printed on a different paper stock. These pages show parts of contact sheets that feature a mostly grim selection of pictures of violence and mayhem, with added colourful markings from the later editing stages. These markings form a visual form of violence in itself, such as when there is a stark red cross right over what looks like the face of a dead man in a morgue.

“At the beginning of 2020,” Herzau concludes his introduction to the book, “I traveled through Liberia once again, experimenting with looking at this country in a different way.” The photographer summarizes the pictures he took as an “attempt to counteract the cementing effect of the one-sided documentation of victims.” We might immediately note that while this goal for sure is honourable, it is unlikely to have the same reach as the ongoing “one-sided documentation of victims” that Western news media continue to produce. After all, a photobook is unlikely to reach even remotely as many people as, say, slides shows by the likes of the New York Times. If anywhere we’d need desperately need to see such a counteraction, it is there. Still, it has to start somewhere, doesn’t it?

“Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title,” Binyavanga Wainaina begins an essay originally published in Granta that accompanies the book. It’s entitled How to Write About Africa, and it includes a long list of stereotypical depictions of a continent that is home to 1.3 billion people living in over 50 countries, states, and territories, yet that in the West mostly exists as this one word: Africa. It tends to make the news only when disaster strikes (much like how, for example, South America typically only makes the Western news when and where someone acts like a dictator).

As a locale, Africa was pillaged by photography more than once. First, photography played an integral part of colonialism. Then, photojournalists descended on the continent to do what Herzau outlined (they still do). Whether or not these two are actually separate developments is debatable. But I’m going to leave it to others to discuss the topic who can write with more authority on this particular subject matter.

Either way, it seems obvious that if one wants to approach a part of the continent with a camera as a professional photographer from the West, then one needs to proceed with care. There is, after all, yet another pitfall, albeit one that also exists in many other places in the world: the dreaded cliché. Wherever you go, it’s hard to avoid photographing the clichés first.

For example, every year, there is a steady trickle of photobooks being published in Germany that reduce the United States to either a home of cowboys or the home of people at the margins. Obviously, there are cowboys in the US, just like there are plenty of people who have to live at the margins. But when the production of photography around these topics basically just serves to cement fairly superficial stereotypes (as is usually the case with these bodies of work), then that becomes a problem.

After all, stereotypes not only simplify, they also serve to disable crossing a divide that makes them arise in the first place. And stereotypes can be produced or re-produced even with the best of intentions. To be able to truly go beyond stereotypes typically requires a lot of work and time. It requires becoming embedded in another country or with another culture, which inevitably entails learning the language. It’s hard work, and whatever payoffs can be had arrive only after a longer period of time.

If you’re a tourist, you won’t get there. As a tourist, you’re a visitor. You’ll be treated well and with care by your hosts. But those hosts won’t let you see behind the scenes any more than you’d do it if someone came to live with you for a week or two. That’s why tourist photographs always look like, well, tourist photographs: you become fascinated with anything that looks different or exciting. Even when you know that photographing certain things shouldn’t really be done, there’s not any more depth to it.

This then brings me to Liberia. While there are a number of really good pictures in the book, after having looked at it a number of times, I’m not an iota closer to knowing more about the country. Instead, I know what Herzau visually responded to. There is plenty of colourful fabric, there is what I would call the African vernacular (aging hand-painted signs, decorations, and images), there are young people playing on the beach. Make no mistake, Liberia is presented as a nice looking place that looks fun to visit. And thankfully, photojournalistic disaster is absent.

But is this enough?

I’m thinking that with Liberia, Andreas Herzau solved a problem, while failing to address the problem. The problem at hand is that none of the many countries in Africa tend to get the deeper, longer-term engagement by Western photographers that is truly necessary to reveal more of their actual essence. Obviously, whether or not a Western outsider will be able to get close to that essence is for another debate. There is much to be said for photographers from the continent to reveal their own view of their home first.

Still, the problem at hand is pretty common in the world of photography: you arrive with your camera, and despite your best efforts to avoid the obvious problems, despite your best intentions you don’t get much further because you can’t or won’t look deeper. In a place like Africa, which has been on the receiving end of so much colonial violence and exploitation, such an approach can only fall short.

Liberia; photographs and text by Andreas Herzau; essay by Binyavanga Wainaina; 128 pages; Nimbus; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.