In the mid- to late-1960s, Eikoh Hosoe and butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata visited a farming village in northern Japan, located in the area where they both had been born. “One thing I remembered from my days as a kid in that countryside,” the photographer wrote much later, “was a sinking feeling we sometimes had, as though something terrible would happen if we dared to venture outside after dark. The fields seemed to be full of ghosts and demons–some of them romantic, some of them awful.” Kamaitachi was the name given to the demon (yōkai) that was the manifestation of the sharp winds: it would inflict cuts on people. (Hosoe quoted from the 2009 afterword to the re-release of Kamaitachi [unpaginated]).

In their artistic collaboration, Hijikata turned into a kamaitachi for Hosoe’s camera, rushing through the landscape and inflicting himself on the mostly unsuspecting villagers who, with the exception of children, appear genuinely puzzled by what’s going on. “Later on,” Hosoe wrote, “I felt I probably owed an apology to those people, who must have been surprised when these two young men appeared out of nowhere and inserted themselves into their daily lives and rituals, snatching babies from cribs and shouting over their shoulders, ‘Sorry, we’re just borrowing your baby for a few seconds!'” (ibid.)

Even though Hosoe and Hijikata’s Kamaitachi and Hoda Afshar‘s Speak The Wind visually have nothing in common, I immediately connected with the Japanese artists’ work when I looked at this new book. That human beings are connected to the lands they live in through a more complex relationship than merely the extractive one Western thinking has established throughout the centuries is still widely acknowledged, even as this takes different forms in different locales.

In the West, these types of engagement with Nature itself are usually couched in dismissive or at least somewhat belittling terms. “On the islands in the Strait of Hormuz,” the publisher’s text about the book begins, “off the southern coast of Iran, there is a common belief that the winds can possess a person, bringing illness and disease. The existence of similar convictions in some African countries suggests that the cult may have been brought to Iran from southeast Africa through the Arab slave trade.” However irrational such beliefs might seem to Westerners, describing them as a “cult” seems unfortunate to this writer.

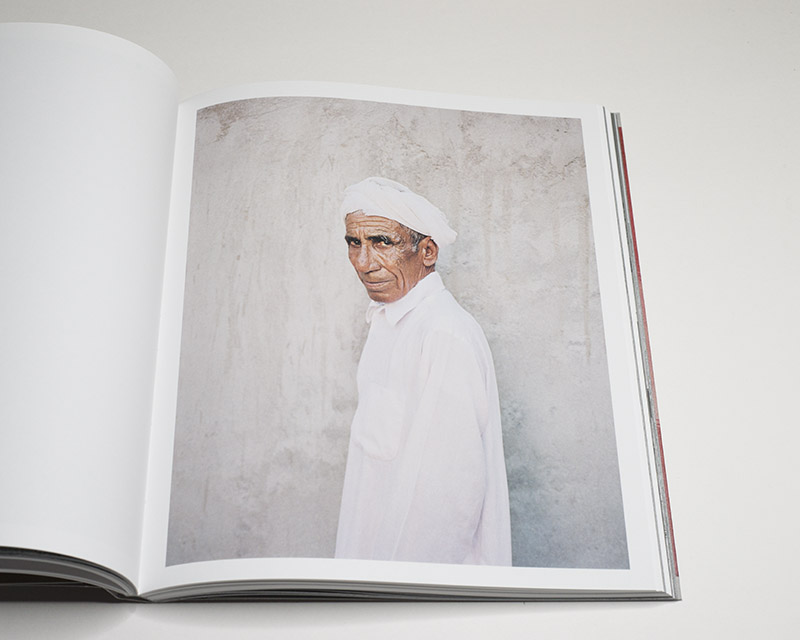

Much like in Kamaitachi, locals appear in Speak The Wind. But the Japanese book’s stark black-and-white expressionism is replaced with a style of photography that is more in line with the medium’s documentary tradition. Furthermore, no added shenanigans are inflicted on the locals by an artist personifying the spirit in question. Instead, their own words and drawings become part of the work itself. For sure, these differences reflect the overall change in sensibility that has happened in photography in the roughly 50 years that separate these two books.

But of course, these differences result in a very different engagement with the two books. Kamaitachi is visually very visceral in the sense that Speak The Wind is mostly not. The former is easier to engage with than the latter, which unfolds much more slowly and delicately. While this in part reflects the fact that the very male in-your-faceness of photography is thankfully on its way out (this is the subjective part of this sentence), it also shows how very similar ideas can be approached in very different ways by different artists.

This is where things get interesting, because the two books not only connect two different cultures far apart on the globe, they also both demonstrate how photography can be art: not by looking like art (which has no substance beyond the showrooms of commercial galleries), but by evoking feelings in viewers who might not have much in common with what they’re made to face.

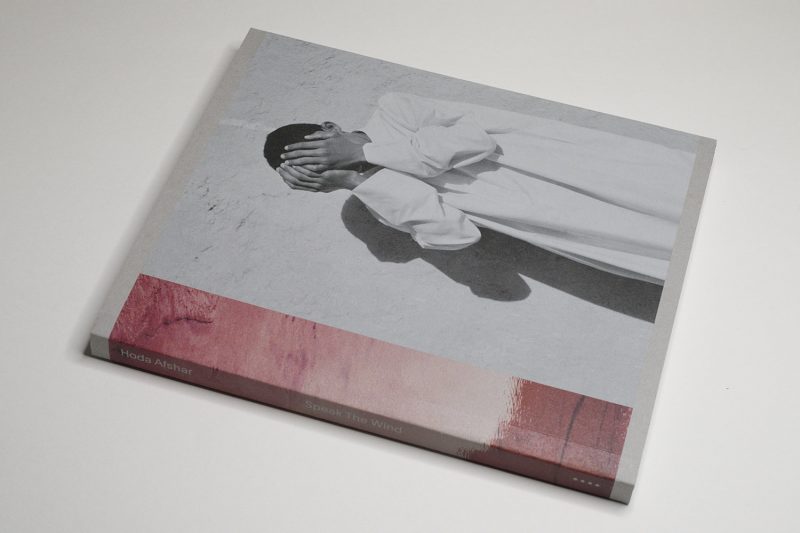

Speak The Wind depicts a land that looks hostile to human life, with its harsh rocky environment in which ochre tones dominate. There is, however, a surprising beauty to the land that Afshar manages to tease out skillfully with her camera. Time and again, photographs of rocks or sand start to simmer with colour, the range of which extends far beyond what one at first perceives as a desert-like monochrome.

There are many photographs of human figures in the book, some of them portraits, others not. How or why I’m making this distinction will become obvious to anyone looking at the book: with a camera, a person can be made to stand for her or himself, or for the rest of us or their community.

There is no story other than the belief that the land and its wind are home to non-human presences. For a book maker, this is a blessing — no need to worry about a beginning and and end, and a curse — all the more worry about a beginning and an end: how do you even allude to something if that’s all you’ve got to do? Afshar does this very skillfully, by building up the idea in such a way that it reveals itself.

Throughout the book, sections of colour photographs alternate with ones in which the pictures are black and white. In the latter sections, variations of the same scene appear. More often than not, these variations do not conform to the page structure, having two pictures appear next to each other in seemingly random locations.

In addition, parts of the black-and-white sections employ pages that were not trimmed at the top, allowing a viewer to peak into a page. There, the viewer finds text: narrations of dreams, and there are drawings of specters and ogres. Here, they are, the demons perceived by the locals, narrated and depicted by their own hands.

Photography’s real strength is to speak of that which is pointed at outside of its own frames. Speak The Wind forcefully drives this idea home, regardless of whether we want to think of the beliefs of the people depicted therein as a cult or as an expression of a different, I’d argue: deeper, connection with the land they live in, a connection that Western thinking has eradicated in many parts of the world. In light of the enormous number of disasters that have been striking this planet just this month — wildfires in many different parts of the world, floods, earthquakes, many of which are the indirect consequence of our own ravaging of this planet’s resources, re-thinking how we deal with the only world available for us to live in sounds like a good idea to me.

Seen that way, if as viewers we allow ourselves to look beyond what separates the people in this book from us, we might pick up more of what the world around us has to tell us.

Here then, the biggest difference between Kamaitachi and Speak The Wind reveals itself. With its very masculine and now dated looking vitality, in the former two artists forced themselves onto the world. With its delicate and accepting grace, in the latter we find an artist listening to the world. For sure, we can use a lot more of that.

Recommended.

Speak The Wind; photographs by Hoda Afhsar; essay by Michael Taussig; 168 pages; MACK; 2021

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 4.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 4.0

Ratings explained here.