For the longest time, economists and politicians alike have been content with playing a curious zero-sum game: as long as the number of jobs lost is equal or smaller than the number of jobs gained, everything is fine. This makes perfect sense for someone who loses a job as, say, welder to then find employment as a welder again, or for someone who loses a job as a customer-relations manager to find the same kind of job again. I doesn’t make all that much sense for the same welder, though, if the only available replacement job is one as a customer-relations manager. Chances are s/he won’t get hired, with the often very likely consequence one of long-term unemployment, living off welfare (where available), etc.

And the places that undergo such a change often don’t do so well for a long time, either — assuming they’re lucky enough to find a second life as a hub for the so-called service industry. I’m writing this piece a little bit less than 10 miles north of the city of Holyoke, which roughly one hundred years ago was booming with its paper industry. Drive down there today, and you’re going to encounter a sight very familiar in developed countries all over the world, with parts of the city being little more than a post-industrial wasteland. Coincidentally, Holyoke is the location where Mitch Epstein‘s Family Business plays out, the story of the photographer’s father’s failing furniture story and rental businesses. It’s a fantastic book, and it’s too bad it’s out of print.

Much like Epstein, photographers have been producing work around de-industralization and its consequences for many years. The process makes for good pictures because dilapidated buildings make for good picture, given their often crazy amount of patina. It’s no surprise that the city of Detroit features prominently in such efforts, and it’s also — thankfully — no surprise that there has been critical push back against what has been termed ruin porn. If you’re interested in some reading on this, John Patrick Leary‘s Detroitism is the best place to start.

It seems clear — to me at least — that an engagement with de-industralization has to have the photographer be very aware of the danger of the patina. A good picture might be a good picture, but a collection of good pictures might pose a large variety of problems, such as simplifying or stereotyping a complex situation. Epstein solves the problem not only by essentially focusing on a single person (his father) but also by adding a variety of different elements (including his own role as the prodigal photographer son who decided to move far away).

A completely different approach would be to work as much towards documentation as you possibly could: this is what the Bechers did. Either way, you just have to do something so your photographs are not being looked at for the patina of what is depicted, because that’s likely to make people think of ruin porn.

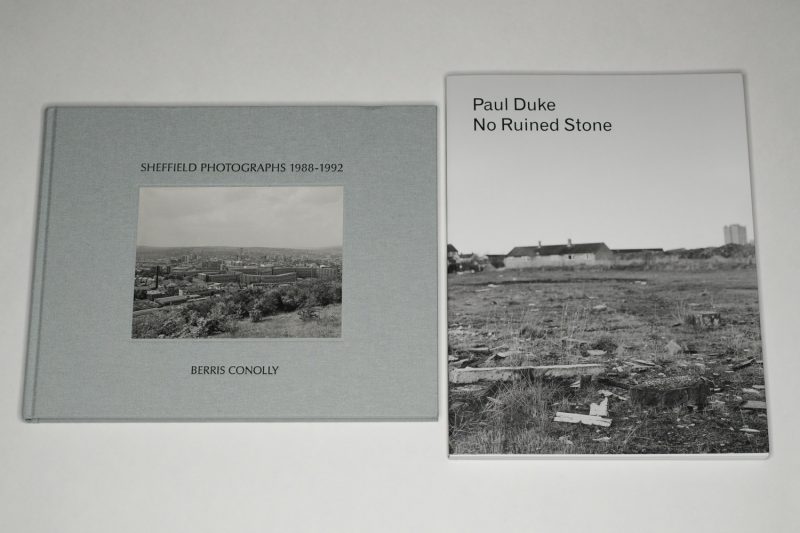

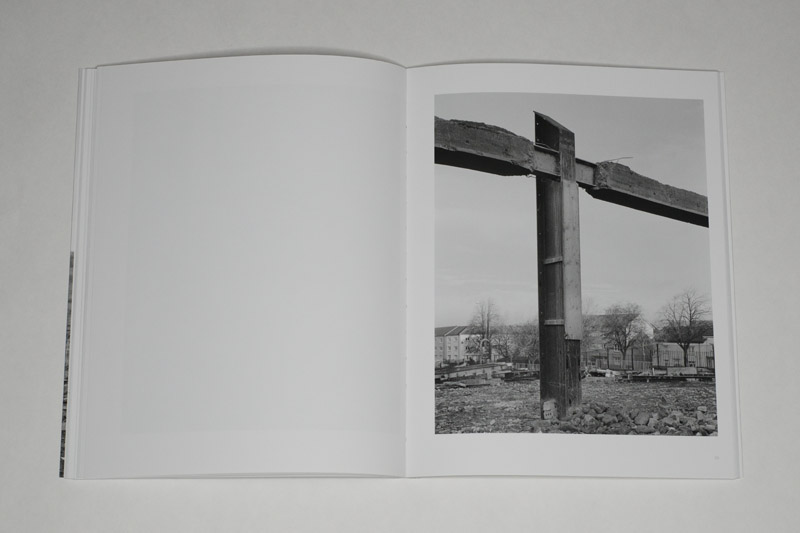

Two recent books approach the same complex, albeit in somewhat different ways. They’re both photographed in Great Britain, and they both describe the consequences of the zero-sum-game thinking that has been the basis of Western economies for many decades. The first one is Berris Conolly‘s Sheffield Photographs 1988-1992. The other one, Paul Duke‘s No Ruined Stone, does not give away location and time through its title: it’s Edinburgh, and the photographs are more recent.

In a somewhat simplifying nutshell (that might still be of some value), Conolly’s photographs follow a New Topographics approach, with its mostly sweeping vistas, often taken from an elevated vantage point. Where people are present, they have mostly become a part of the very landscape (or scene) in front of the camera (if the two distinctly different photographs, group portraits both, had not survived the editing stage that might not have been so bad).

There’s much that can be said for and against this photographic approach. What can be said against it I think is mostly based on what certain Düsseldorf School photographers (ja, ich meine Sie, Herr Gursky) developed from it, namely an obsession with photographic practice at the cost of much — if any — insight to be gained. Conolly stays in what I would consider the sweet spot, the only one that truly deserves comparisons with older types of paintings, where individual figures aren’t reduced to being mere ants and thus still contribute as much to the photograph as the scene they find themselves in.

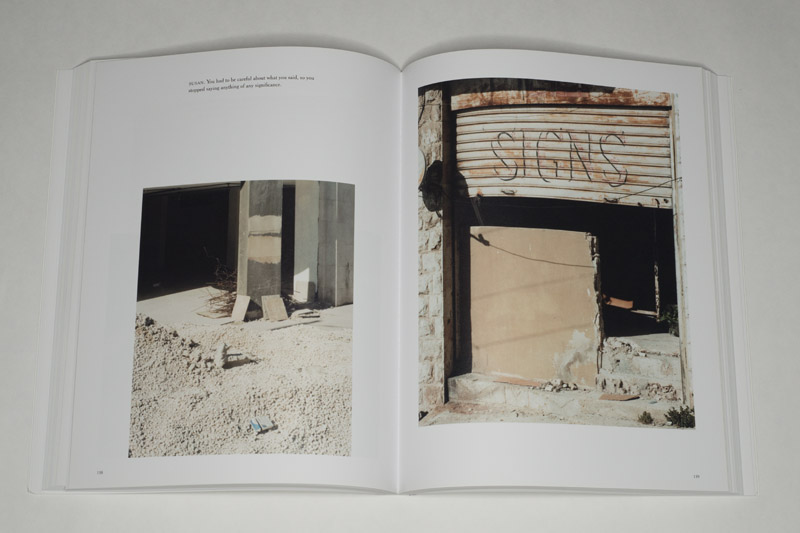

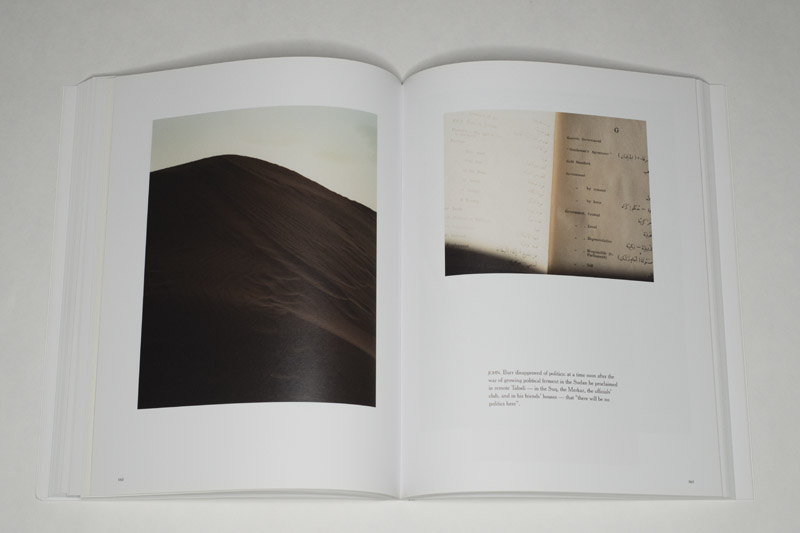

In contrast, Duke is physically much closer to his subject matter. The viewer can see — and feel — the surface of what is being photographed, whether it’s the brick walls suffering from general neglect or the skin of his subjects, people who have had to endure being alive under these specific circumstances. The portraits are most welcome here: without them, the depictions of facades of building would just not suffice to get a viewer engaged. This is not because they’re bad pictures — on the contrary. It’s simply because the human presence needs to be explicitly spelled out. Depictions of graffiti or whatever else just don’t have the same emotional power.

If Conolly’s approach follows the New Topographics, then I don’t know what movement to assign to Duke. But his photographs have much in common with, let’s say, Ute and Werner Mahler‘s recent Kleinstadt, for which — thankfully — there now is a second edition. Clearly, there’s a difference in both the demographic and the artistic sensibilities (which becomes most clear in the portraits). But these days, this rather understated form of subjective documentary is proving to be very strong. In parts, I suspect, its attraction might come from the world of photography having witnessed what happens when the New Topographics go awry as photographers become too obsessed with cameras and print sizes.

Both Conolly and Duke show the effects of the zero-sum-game thinking that I mentioned in the very beginning: cities are being left to decay until someone brings in the sevrices industry (or not). Meanwhile, people living in the social housing erected along the way have to make do with the increasing strain they’re subjected to as neoliberal politics focuses on funneling ever more money into the coffers of corporations instead of taking care of those most in need.

Obviously, there is only so much photographs can do to change the world. Given the time its photographs were taken, Sheffield Photographs 1988-1992 now is more valuable as a historical document than a call to action (whatever that action might be). But the connection with No Ruined Stone is interesting, because while taken in different locations, the two books cover different aspects of the same thing playing out in front of our eyes: ultimately, the victims of the political zero-sum game always are people.

The neofascist populism — inevitably tied to racism, xenophobia, and other injustices — that has been sweeping the globe has made it very difficult to engage with the topic, because a simple narrative (still used widely in the US press, here‘s an example) is too simplistic and problematic. Regardless, somehow, we will have to find a solution — not just to get the neofascists out of power but also and especially to get back to the idea of a more just society, a society that values all its members equally.

Sheffield Photographs 1988-1992; photographs by Berris Conolly; essay by Geoff Nicholson; 104 pages; Dewi Lewis; 2019

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6

No Ruined Stone; photographs by Paul Duke; essay by Martin Barnes; 112 pages; Hartmann Projects; 2018

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6