A little while ago, I found photographs by Federico Clavarino in a German magazine. They were of Italy, a place that I have visited a few times and that I have found resisting to being photographed very thoroughly. To begin with, its general infrastructure is not very attractive at all. (I suppose you could say that for pretty much any country, even though for example in the US it’s so run down and neglected that what might come across as patina becomes photogenic again.) And then the countryside and everything historic is so photogenic that it’s almost sickening — these days, maybe the best way to describe it would be to say that it’s just all instantly instagrammable: it’s very easy to make a picture that looks great, but it’s very hard to make one that offers more than that.

In his Italian photographs, Clavarino solved this problem by fragmenting the location into what I think of as slivers. All photography fragments a location, of course, but in this case I mean a very severe type of fragmentation where what is being presented is so cut off from what was around it that it takes on a very peculiar relevance. It is the Egglestonian approach, albeit without the general sense of the photographer being a tad too blasé, the sense that permeates the American photographer’s work.

There was a new book, the German magazine told me, and I was very much looking forward to seeing it. As it turned out, the new book (Hereafter) has nothing to do with the Italian photographs. Those, I realized, had been published as Italia o Italia a few years ago — in fact, I had even reviewed it (alas, my efforts to locate the book in my library failed due to a general lack of organization — so it goes). My anticipation of seeing one thing, only to then receive another, had me confused.

In theory, this is something you, the reader, probably don’t care all that much (if at all) about. And I wouldn’t mention it here if I had not spent a bit of time thinking about how when approaching an artist’s work one’s expectations might cloud what one is about to encounter. I’d like to think that as someone who regularly writes critical pieces this is something I’m immune to, but that’s clearly not the case. Even without the little episode described above, I might approach Hereafter differently, were I not familiar with the earlier work.

But this conundrum — let’s call it that — cuts both ways: an artist might produce a new body of work that looks just like the earlier ones, and as a critic you’re left to wonder how or why this could possibly be interesting for anyone, first and foremost for the artist. Or an artist might produce something radically different, and you’re left to wonder why this radical turn… I don’t think there is an ideal situation here. In any case, artists ought to do what they feel is right; and critics then should do the same.

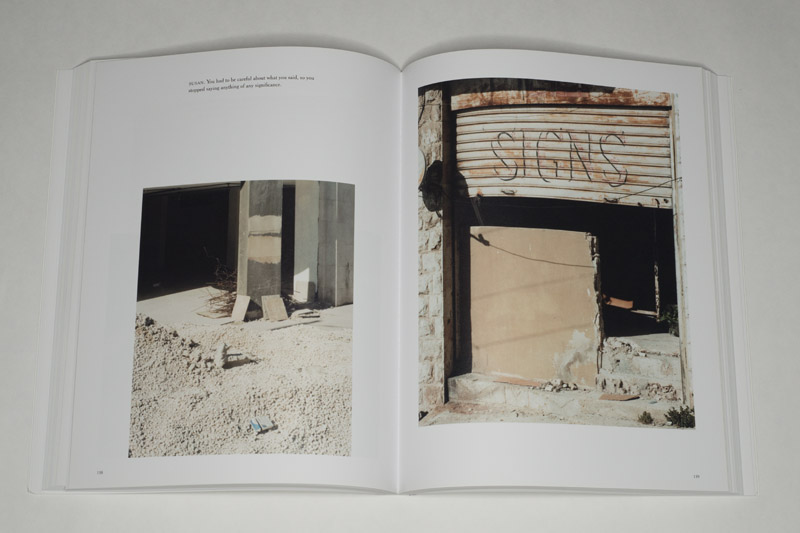

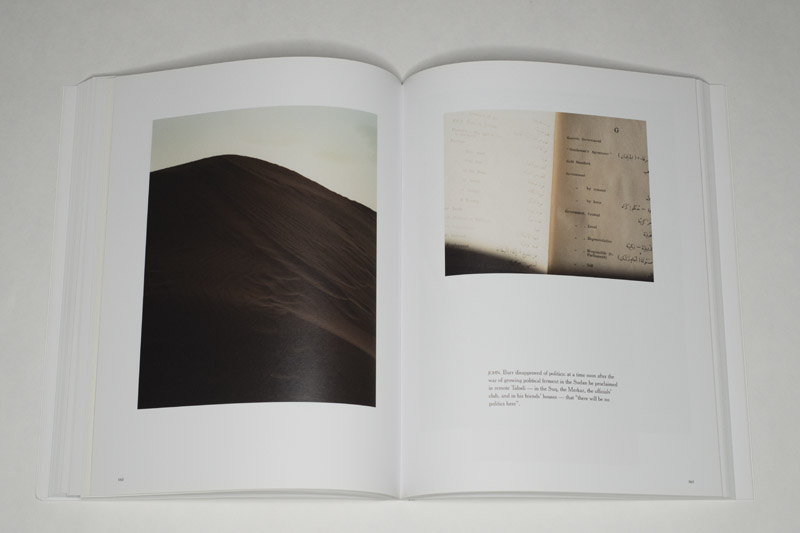

In Hereafter, Clavarino brings his photographic approach to a variety of locations beyond Italy, places that had been part of the colonial British empire. In addition to the straight photographs, there are reproductions of vernacular photographs and documents, there are photographs of older items (still lifes of sorts), there are portraits, and there are ample short text pieces, all of them read like transcriptions of the recollections of those in the portraits.

I find those recollections unpleasant to read. With their casual descriptions of life as some form of colonial administrator, the narrators are clearly unaware of, if not uninterested in the fact that colonialism was just a label for occupying and plundering other nations, the effects of which haunt larger parts of the world today (as an aside, this form of willfully oblivious denial now animates larger parts of the Brexit camp). Maybe this is the idea of the book — to be honest, I can’t tell. Those portrayed and given voice, after all, are part of the photographer’s family. I’ve found that outside of Germany (where many descendants of Nazis have produced very harsh judgments of their predecessors) people seem to be a lot less eager to face and judge their forefathers’ and -mothers’ failings.

This unmasking of the casual cruelty that provided the base of colonialism, where a bunch of seemingly highly educated people set out to rule over those explicitly or implicitly deemed inferior, is of course most welcome — most welcome in the West, that is, because those previously lorded over are very much aware of how they still have to deal with the aftermath.

I have one concern, though, namely that Clavarino’s straight photographs and the rest of the material are at odds with each other. (And it is this realization, right here, that had me write the thoughts in the very beginning of this review.) In a nutshell, he is such a good photographer that the other material simply pales in comparison. The words are simply too off putting (for the reasons mentioned above), and the documents and archival photographs aren’t remotely interesting enough to hold their own next to Clavarino’s tender, yet forceful pictures (the still lifes fall along the lines of the documents). So for me, it’s almost like looking at two different books at the same time. Truth be told, when I look at the book, in four out of five cases I only look at the straight photographs.

Those photographs don’t tell the whole story, of course, and maybe this is me ultimately writing a review of a book I’d prefer over the one at hand. Maybe. But the fact remains that just like in the earlier Italia o Italia, as a photographer Clavarino is able to distill the essence of a place into something intriguing, something that doesn’t feel familiar. In contrast, those archival photographs and documents (even, to some extent, the narration by the colonialists) — they are all familiar.

Given I often don’t rate books that contain some or a lot of archival material, that’s helping me out of a pickle here. I don’t know how I would rate the book, given its parts work so differently for me. Even in terms of its overall construction, the book works — all these materials come together to tell their story. It’s just that I like those straight photographs so much that everything else is made to more or less disappear.

For sure it’s a recommended book — you might simply not share my misgiving, and regardless, this particular photographer’s work deserves to be seen and appreciated a lot more widely.

(not rated)

Hereafter; photographs by Federico Clavarino; 264 pages; Skinnerboox; 2019

Ratings explained here.