Over the course of the Iranian revolution, one repressive murderous regime was overthrown, to be replaced with what would turn out to be another, albeit different repressive murderous regime, the one that is still ruling the country. I suspect that many (if not most) of the details of the revolution will not be familiar outside of the country — and why would they? Revolutions tend to be messy, and more often than not those who end up in charge are not necessarily the ones who spoke up and took to the streets first.

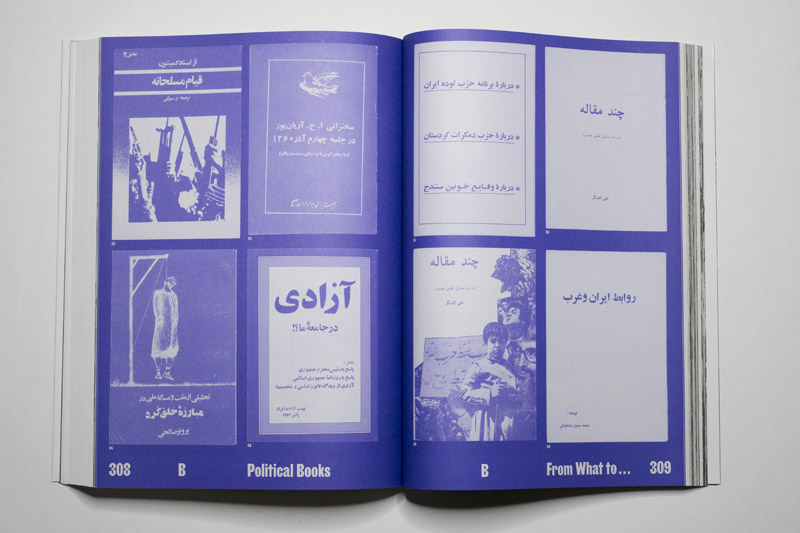

As it turns out, photobooks — or books that relied to a large degree on photographs to convey their messages — played a considerable role during and after the revolution. As the Shah’s regime fell, so did its censorship, which resulted in a flurry of publications of material. But even before there had been Samizdat style publications, often produced with shoe-string budgets, which essentially pushed for a freedom of expression where the state wouldn’t have any of that.

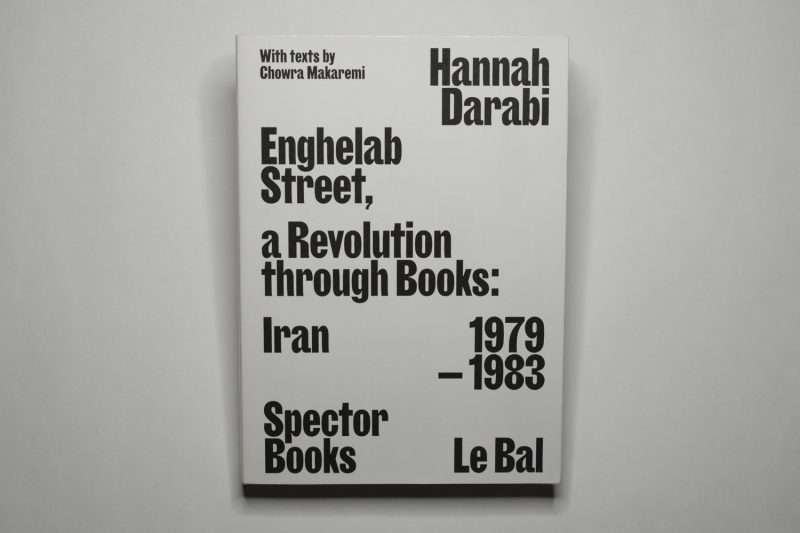

I know all that not because I am an expert on Iran or its photobook scene but because of Hannah Darabi‘s Enghelab Street — A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983 (those living in the US might want to use this link if they want to place an order). The book is one of the latest additions to the ever growing number of books about photobooks. My own thinking about such books has evolved with time, and I now think that they are most interesting where they pursue a specific angle that takes the photobooks out of the very narrow niche they are typically contained in, to address a larger idea or topic — as is clearly the case here.

Against the background of the political revolution in the country and the subsequent attack by Iraq (which led to the gruesome war that was to last eight years), Enghelab Street ends up serving multiple purposes. To begin with, it chronicles the history of the years 1979 to 1983, with copious added texts (and interviews) by Darabi and Chowra Makaremi providing much needed further insight and background information. Beyond the broader markers of that history a large variety of interesting details are being exposed.

Second, given that there was no history of the photobook in Iran before 1979, the book shows activists, photographers, and artist experiment with what a photobook could look like and how it might communicate its intended ideas or messages. This would include seemingly basic questions such as what could a documentary photobook look like? As I think we all know, this is anything but a simple question — but if there are no models to follow, dealing with it obviously poses very different challenges than, let’s say, attempting to improve upon earlier models (and avoiding their shortcomings).

Third, the publications discussed in Enghelab Street were not made for photobook fairs, nice bookshops in major cities, or the sections in museum gift shops where books are displayed. They weren’t made for fellow photographers, they were made for a larger audience that was as hungry for basic human rights as the makers of the publications themselves.

The combination of these three factors had (and has) me very interested in what the book has to offer. It seems obvious to me that especially in the West a much better understanding of Iran is needed (for reason that I hope are pretty obvious). I feel that this is something the West actually owes not just to Iran but to all the various countries it has been exploiting over the course of the past few hundred years.

Beyond that, though, I also feel that a breath of fresh air is very desperately needed in the world of photobook making. This world of which I obviously am a part appears to be very content with its walled garden: its nice bookshops and its photobook fairs (that might or might not be attached to equally walled-garden like photography fairs), its limited editions, its books a huge fraction of which are literally of basically zero interest to anyone who’s not tending to the garden. It needn’t be that way.

I firmly believe that operating in the walled garden is more a choice than a necessity. As the books in Enghelab Street demonstrate, photobooks can be made for larger audiences, and they can address larger, pressing topics. This is not to say that every photobook ought to do that. But to see the dearth of photobooks dealing with, let’s say, the assault on Western democracies by so-called populists or the assault on the rights, well-being, and dignity of some of the most vulnerable people in the world, refugees and migrants — that’s very disheartening to me.

Of course, there are a small number of such books, and every once in a while a major photography prize (funded by the very same financial institutions who are maintaining the mess we’re finding ourselves in) throws some token appreciation at one of artists responsible. But it seems to me that given the multitude and extent of the challenges we’re currently facing, there could be a lot more.

In the end, photobooks are very unlikely to change the world. Just look at Enghelab Street: the books did not prevent the re-creation of censorship and of another repressive regime in Iran. But still, I’d argue that the genie was still out of the bottle, and it still is.

Enghelab Street — A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983; texts and interviews by Hannah Darabi and Chowra Makaremi; 540 pages; Le Bal/Spector; 2018