László Moholy-Nagy‘s Painting, Photography, Film is a remarkable book. At first sight, it feels dated. Its design betrays its modernist Bauhaus origins, its photographs speak of a time when the medium was still in its relative infancy (certainly compared with what we are used to now), and the references in the text speak of a very different time when there was considerable promise in technological developments, the equivalents of which today fill us with dread. But to engage with the book on that level will miss the most important aspect: much like how Walter Benjamin‘s famous essays still have the power to inform us today, so does this book. In particular, it’s Moholy-Nagy’s spirit that can teach us a lot.

Brief digression: The inversion I mentioned just now provides an interesting aspect when comparing Moholy-Nagy’s times and ours. Thinking about it, maybe it’s not so much an inversion as a sense of déja vu: having seen the promises of the mechanical revolution turned into environmental pollution and fascism (to give just two examples), a sizeable number of us are weary of what the digital revolution might lead to (early warning signs aren’t looking very good at all).

Moholy-Nagy was deeply invested in what photographs could do and how they would do it. His apparent belief in the medium’s role as a positive force to bring about a better world might now seem at best quaint and at worst naive. However, the necessity to explore the medium has not disappeared. In fact, it has been vastly amplified in a world driven by images. Were he alive today, Moholy-Nagy would be endlessly fascinated by the world of photographs and images we are immersed in.

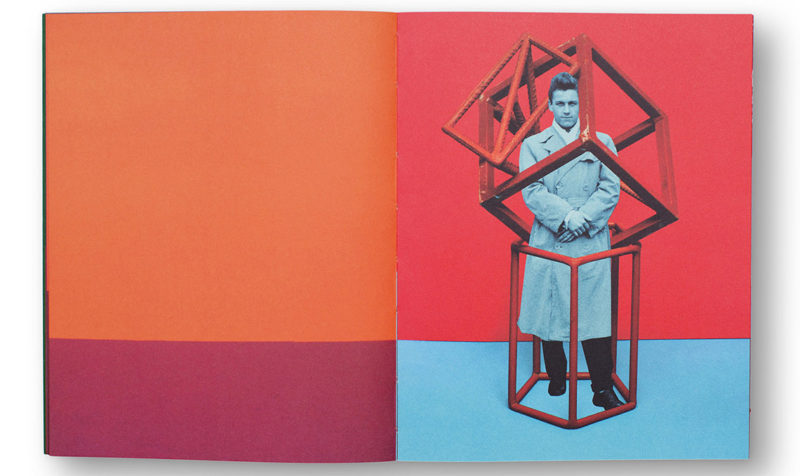

In a large variety of ways, Thomas Ruff is Moholy-Nagy’s heir. If any artist is concerned with photography’s ability to render the world and our own ability to understand it, it’s Ruff. While other artists share similar sensibilities — Christopher Williams or Roe Etheridge come to mind, none comes close to the sheer breadth of Ruff’s vision and willingness to push the boundaries of photography. At the same time, there is a levity to his approach that I find lacking in his contemporaries’ works.

With Ruff, you never quite know what you’ll be getting next. You can be certain that it will be interesting, even if the results might at times leave you cold. It is exactly this spirit of inquisitiveness that carries Moholy-Nagy’s torch. There even are various direct connections, such as, for example, Ruff’s marvelous computer-generated photograms — it’s not hard to imagine Moholy-Nagy being utterly delighted were he able to see them. And it is exactly this combination of inquisitiveness and visual delight that these two artists share.

If Winogrand photographed to see what the world would look like in pictures, Ruff makes photographs to see what the photographs he imagines might look like. What would a photogram in full colour look like? What would an astronaut flying over Mars see? What do images look like that move far beyond the male gaze, to show us a much fuller spectrum of human sexuality?

Ruff usually is being talked about as a member of the Düsseldorf School. I can understand this approach — it’s true in a very obvious sense. But its real utility has now exhausted itself. Where most of his Düsseldorf peers have barely moved beyond what they were doing a decade or two ago, Ruff sped up his investigation of photography, breaking all boundaries of both what photographs are and what they can look like. This becomes apparent in Thomas Ruff, the catalog of a retrospective currently on view at London’s Whitechapel Gallery (which those unable to visit the exhibition — like me — will have to be content with).

Unlike the other Ruff catalogs I own, this particular one offers a deeper glimpse into the artist’s universe through a series of text fragments provided by the artist, which outline his intellectual approach. These fragments include a longer quote from Painting, Photography, Film — which confirmed my idea that Ruff is very much aware of the territory he is operating in, along with many other quotes from a variety of sources, some of them expected (Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes), others perhaps less so (in particular Thomas Bernhard or Michel Houellebecq).

Having met and spoken with Ruff a few times, my guess is that this is going to be the closest we will get to seeing him provide more of his background vision. There will not be his version of Moholy-Nagy’s book. However, it’s not clear what such a book might look like anyway — Moholy-Nagy’s messianic spirit would feel quite odd to me in these times where images move and change faster than anyone could describe, where photographs are everything and nothing at the same time.

One can only hope that Thomas Ruff will continue his exploration (yes, his is an actual exploration) for a long time. While our technologies have moved far beyond the ones available to Moholy-Nagy, our thinking about photography still is very much at the stage of that time — and I doubt it will ever move beyond. We still talk about pictures as if they were the fully indexical pieces of the world that they can be but usually are not. We still get mad when a picture doesn’t have the effect we wish it had. We still produce pictures at a seemingly maddening rate. As long as someone like Ruff picks up a piece that interests him, to look deeply into what it might mean, how it might work, how far it could be pushed, we should be good.