Lists are silly, but we all love them (at least in some ways). Photoland spends obsessing over lists for roughly six weeks every year, the best of this or that… You know the drill. Given I am really only seeing a fraction of all the photobooks produced, I think the idea of a list of the “best” photobooks doesn’t make much sense for me (see some statistics etc. here). I’d rather talk about my favourite books – that small subset out of the group that somehow made it into my hands, resonating most strongly.

This year, I started using a rating system for photobook reviews. I haven’t seen it adopted, even in modified form, anywhere else. So it doesn’t seem the idea is overly popular. Or maybe people aren’t so willing to say in public what they’ll talk about over a beer. Regardless, having to look at each and every book based on a more strict system has made me look more carefully at books. It has deepened my engagement with photobooks.

The rating system runs from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible rating. Most of the books I review end up somewhere in the range between 3 and 4. Some books rate more highly, a few less so. This doesn’t reflect the rating system itself as much as my decisions which books to review and which ones to pass over.

It has been noted that photoland has a big problem with negative reviews – there are hardly any. Realistically speaking, there are way more bad photobooks than good ones, and there isn’t much to be gained from reviewing most of those bad ones. Also, and this is important to me, if someone barely known, publisher or photographer, produces a bad book trashing it doesn’t feel right. Major publishers or big-name photographers – that’s another story. So that’s where I’m coming from.

There are quite a few books that I still have to review. Obviously, those are excluded from the list of rated books. Some of them are also excluded from the list of my favourite books – they’ll simply be on next year’s list.

There is some overlap between the list of books most highly rated in this system and the list of my favourite books. I’m actually glad that these two lists aren’t identical: there are some things you simply can’t measure. It’s art. The ratings provide some important measures for what matters in a photobook. Beyond that there is… all that which is subjective.

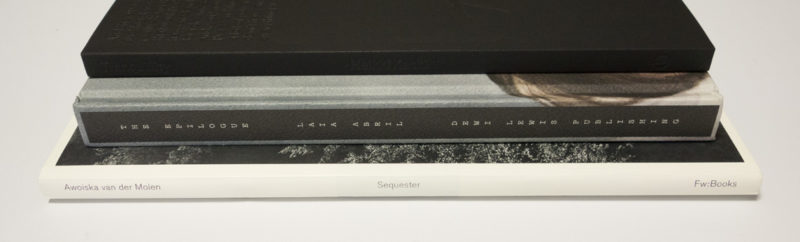

Here then are all the books with ratings equal to or higher than 4 (note that this list only includes book I already reviewed – you can find the reviews in the archives): Heikki Kaski – Tranquility (Lecturis 2014) 4.9; Awoiska van der Molen – Sequester (Fw: 2014) 4.7; Laia Abril – The Epilogue (Dewi Lewis 2014) 4.5; The Sochi Project – An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus (Aperture 2013) 4.3; Peter van Agtmael – Disco Night Sept 11 (Red Hook Editions 2014) 4.3; Tobias Zielony – Jenny Jenny (Spector 2013) 4.3; Willeke Duijvekam – Mandy and Eva (self 2013) 4.2; Philip-Lorca diCorcia – Hustlers (Steidl 2013) 4.1; Joan Fontcuberta – The Photography of Nature & The Nature of Photography (MACK 2013) 4.1; Mayumi Hosokura – Crystal Love Starlight (Tycoon Books 2014) 4.1; Cristina deMiddel – Party. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung (AMC/RM 2014) 4.0; Jim Goldberg – Rich and Poor (Steidl 2014) 4.0; Muge – Going Home (Jiazazhi 2013) 4.0; Michael Schmidt – Natur (MACK 2014) 4.0.

And these are my favourite books this year (in no particular order really):

Harvey Benge‘s Some Things You should Have Told Me (Dewi Lewis 2013) should have been on my list last year, the only reason why it wasn’t being that I forgot to add it. It’s the kind of book that looks and feels somewhat unassuming until you realize what it really has to offer.

I have always loved Muge‘s pictures that became Going Home (Yanyou Di Yuan 2014), and the book truly doesn’t disappoint (review).

I am convinced that Peter Van Agtmael‘s Disco Night Sept 11 (Red Hook Editions 2014) will ultimately find itself in the company of those few books that powerfully speak of the folly and horror of war in a lasting manner. This book is going to be the book about the so-called war on terror, which resulted from imperial hubris as much as incompetence, a deadly and terrible combination when in the hands of those who find themselves in power (review).

Julia Borissova‘s Vegstvo Na Krai [Running to the Edge] (self 2014) displays the true beauty of self-publishing.

Philipp Ebeling‘s Land Without Past (Fishbar 2014) finds another young German photographers trying to cope with his country’s past (review).

From what I can tell, Eamonn Doyle‘s i (self 2014) appears to rub some people the very wrong way, which is marvelous. It’s a book I didn’t think I’d like this much (review).

Daisuke Yokota has been churning out way too many books. Linger (Akina 2014) is a true gem that makes one forget most of the other ones (see my article about the photographer).

As much as I do not appreciate the size and production itself, Katy Grannan‘s The Nine/The Ninety Nine (Fraenkel 2014) is great.

At a time when so much photography is so unwilling to be, well, sexy, Mayumi Hosokura‘s Crystal Love Starlight (Tycoon 2014) shows us what photography can do, and I think it really helps it’s not another middle-aged guy photographing much younger female models (review).

Laia Abril‘s The Epilogue (Dewi Lewis 2014): Smart and clever and heartfelt – yes, you can have all three of these. The book raised the bar for those trying to tell documentary-style stories considerably (review).

I had been looking forward to seeing Heikki Kaski‘s Tranqulity (Lecturis 2014) since it won an award I was a jury member of last year, and it didn’t disappoint. Possibly the one book I’d pick as my most favourite book this year (review).

Awoiska van der Molen‘s Sequester (Fw: 2014) presents the underlying work in a very smart way, allowing the viewer to engage with the photographs, which in theory really require the presence of the artist’s magnificent prints, through the medium photobook. Intensely beautiful (review).

Masako Tomiya’s Tsugaru (Hakkoda 2013) was one of the surprise finds this year (thank you, Peter!). Somewhere between Issei Suda and Rinko Kawauchi, bringing the best of both to photography (review).

Arwed Messmer re-worked East Germany’s Stasi (Ministry for State Security, officially known as MfS, colloquially known as Stasi) archives, going beyond the creepy or weird, and pointing at the outright evil (I’m not using this word lightly), while showing the role of photography: Reenactment MfS (Hatje Cantz 2014).

Federico Clavarino ‘s Italia o Italia (Akina 2014) deals with the state the country is in, in ways that aren’t quite so obvious and near the surface. A surprisingly engaging and deceptively simple book.

Did I need another book by Thomas Ruff? Well, yes, I did: Editions (Hatje Cantz 2014) presents this artist’s work, based on special editions he has been making over the years, using a variety of often unusual printing processes. I’m a big, big fan of Ruff, and this book adds a lot to the canon.

Cyril Costilhes‘ Grand Circle Diego (Akina 2014) is another Akina book in this list. I hope the publisher won’t repeat the various mistakes other publishers have made in the past, when popularity resulted in too many books, severely diluting quality… We’ll see. Regardless, Grand Circle Diego is an impressive book, full of mystery and terror; and I have the feeling it’ll ruffle some feathers.

It takes someone like Rafal Milach to make a book like The Winners (Gost 2014), where you take a very simple and seemingly obvious idea, to present it in a way that’s deeply engaging and often bitingly funny. A brilliant example of the form of a photobook really enhancing its function. Oh, and would there please be a second edition so that people who haven’t seen it can get their copy as well?

Shomei Tomatsu‘s Chewing Gum and Chocolate (Aperture 2014) turned out to be a bit of a surprise for me. Expecting a fairly obvious compilation and/or re-release of older, known work, the book instead presents what could or maybe should or maybe just might have been the eponymous book the artist had been planning to make for a while. Included are a few very good essays, which make it a must buy for anyone interested in photography from Japan.

Rosalind Fox Solomon‘s Them (MACK) has so far resisted my attempts to review it, which might just be a good sign. Of all the books recently made in/around Israel and Palestine by far the very best I think.

I found Abigail Heyman‘s Growing Up Female (Holt, Rinehart and Winston 1974) in a second-hand bookshop for $6, and I ended up being blown away by its beauty and power. Forty years later, things haven’t really changed that much – a book for our times (find a few thoughts about it here).

Lastly, there’s Issei Suda‘s Waga-Tōkyō hyaku (Nikon Salon Books 5. Tokyo: Nikkor Club, 1979), which was re-released in 2013 (note the previous link points to the re-release). I was given the 1979 copy (thank you again, Peter!), and it has become a book I have spent a lot of time with this year.