One of the mostly unacknowledged problems of contemporary photography is that most of its – tangible – products are luxury objects. The world of galleries and art fairs has long become the Circus Maximus for the rich and superrich, and we don’t even bat an eye over that any longer. There lies considerable irony in the fact that many artists are not nearly as wealthy, or are, in fact, merely getting by, paying exorbitant rent in places like Manhattan or Brooklyn simply to have a chance to if not have a crumb of the cake, then at least be able to gawk at it. Yet, their goal is to enter the very exclusive world that is keeping them out or that might admit them, however briefly.

The problem gets compounded when the photography in question revolves around the less fortunate, as is often the case in contemporary photography. The poor, the homeless, the less-well-off – that’s the Other that can be made subject of pieces of paper that sell for thousands of dollars and that, ideally, both make us reflect (but, please, not too much) and is decorative (looks great over the couch). There’s something obscene about this particular business.

One of the advantages of photobooks is that they lift the problem out of the stratosphere. Photobooks are still luxury products, but they (usually) are much more affordable than photographic prints. As a result, the audience of photobooks is much wider. Needless to say, “much wider” is somewhat relative. We’re speaking of an expansion of the audience of a handful or dozen to, at best, hundreds or thousands (interestingly enough, we don’t consider the photobooks that sell tens or hundreds of thousands of copies as real photobooks). Despite all the excess in photobook making that we appear to be witnessing right now (and that, if what I’m hearing, is to be believed, is about to at least partially deflate), a photobook simply allows for a different conversation.

That said, as I noted above most photobooks are luxury objects for a variety of reasons, price maybe not even being the most crucial one. You do need to have those extra $50 or $75 to be able to afford a photobook (if you think that isn’t much money, calculate how long you’d have to work for that if you made minimum wage). At the same time, photobooks live in an exclusive environment, in part by choice, in part by necessity. Your photobook is very unlikely to make it into, let’s say, that tiny section at your local corporate or non-corporate book shop that says “Art” or maybe even “Photography.” You don’t have a distributor, or your distributor won’t reach those places – or will simply know better not to send copies there.

Given the incessant brouhaha over social media, the one thing that truly irks me the most about it is the usually completely uncritical acceptance of any of the hype coming out of the tech companies, while essentially none of the challenges for photography that I laid out above are being dealt with. In much the same way, when graduates from photography MFA programs talk to me, their sole focus tends to be on how to get into galleries or how to get your book published. It is almost as if there are no other options available. It is as if there is almost no imagination to challenge a system that is working OKish on the whole (a small number of photographers make a lot of money, quite a few make some, most make very little or none), a system that essentially fails to deliver the promise of contemporary photography to all those people who are not already in the know or part of the scene.

We should, of course, be making work that appeals to people in the know. But I believe we should also be making work for those who are not. In particular, if our work is about a group of people who is not included in our world, wouldn’t it be almost a logical step to invite them in? To share with them what it is that is being created around them or about them?

There are options. For example, over the course of ten years, Zoe Strauss exhibited her photography on the pillars of a highway bridge in South Philadelphia. The Sochi Project offer exhibitions that come in the form of fairly cheaply produced prints on paper that you can paste on whatever wall is available (I’ve seen these installed – they look great).

Another example is provided by Paolo Woods, about whose work I want to talk in more detail. In 2007, Woods and writer Serge Michel went to ten African countries and to China. China’s massive influx of investments and people in the Africa has now become a hot topic (see, for example, this article). Back then, the story was relatively unexplored. They made a book, which eventually appeared in eleven translations, and which also made it to China and Taiwan. The reactions were a surprise for the photographer:

“What was very interesting for me was that my work was seen and debated in, amongst other places, Washington, Paris, and Beijing. The Americans (and the Taiwanese) saw the work as the proof that the Chinese were conquering Africa, becoming a new repressive colonial power. The French saw the work as proof that they were loosing ground quickly in what is known as La Françafrique and the Chinese saw the images as glorifying their courageous pioneers to the new Wild West and almost as a DIY manual for success abroad.”

It has been long known that photographs have no fixed meanings. Here is a prime example of how meaning arises in part out of one’s cultural background and ideology. As a photographer, you have a set of options available how to deal with such a reception of your work. You can, for example, try to enforce whatever message you want to convey, trying to restrict the meaning to a very specific one. Or you can realize the medium’s freedom, the way photography operates and work with it. Woods opted for the latter:

“I saw all this as the proof that photographs are not closed things, and that their meaning depends not only on the author, on what they depict and the context, but also, very much so, on the viewer, his culture, his knowledge. It became clear for me that I did not want anymore to produce work exclusively for a western audience, whether somebody reading the book, a gallery goer or a collector, but [I] wanted to bring it back to where it came from, back to the people I had photographed and gauge their reaction to it. So we presented it to Zambian members of Parliament and to the leaders of the opposition, to African artists and intellectuals, to Chinese ambassadors and businessmen. The book was available in many African countries.”

A follow-up project with the same writer focused on Iran. After the crushed 2009 Green Movement, Woods and Michel were kicked out of the country, resulting in a loss of any official venue for the work there. But in this day and age, there still exist avenues to disseminate work:

“What we decided to do was to get the book translated in Farsi, the language spoken in Iran, and we created a PDF of the book identical as the one in French but in Persian. We did two versions. One […] with the images in low resolution that could easily be downloaded with a slow internet, and one with the images in high resolution with the photos that could be printed in bigger formats. We burned dozens of USB keys and got them in Iran. But even more important we gave the free PDF in downloadable form to all websites, blogs, individuals that we could think of and that could spread the book in Iran. We hired a young Iranian woman that had been our fixer there and lives in exile now, to make a Facebook page of the project in Farsi and to respond to the hundred of emails that poured in.”

Afterwards, feeling dissatisfied with visiting places to cover, Woods decided to relocate to Haiti, to live and work there. He teamed up with Arnaud Robert who had already spent ten years writing about the country. Haiti’s history is complex, as is its current state, a complexity that is not necessarily reflected very well at all in how the country is perceived abroad. It’s quite likely most people will only know of the massive earthquake that hit the country fairly recently or maybe, if they’re a little older, the ghoulish dictators that ruled the country. But beyond that there will be little, if any, knowledge.

A poorer country’s dysfunction usually can only be understood if internal and external factors are looked into, and this is what Woods and Robert looked into:

“We analyzed the different forces at stake: the State obviously and it’s head, the president, the love-hate relationship between the people and the power, who the people in power actually are. And then the substitutes to the dysfunctional state: the UN force based in Haiti, the NGO’s, the American Evangelicals coming to ‘save the Haitians from the devil,’ the rich Haitians and their powerful families.”

In 2013, State , the result of their work, was published. The work was premiered at the Musee de l’Elysee in Switzerland, to good reviews; and collectors started buying prints. Given that Haiti is one of the poorest states in the Western hemisphere, only the rich depicted in the book would have had a chance to visit the exhibition there, or buy photography (which was, given their reaction to the chapter dealing with their world, unlikely). Yet again Woods wanted to bring the work to a larger audience in the place he had spent so much time looking at, in fact working and living in:

, the result of their work, was published. The work was premiered at the Musee de l’Elysee in Switzerland, to good reviews; and collectors started buying prints. Given that Haiti is one of the poorest states in the Western hemisphere, only the rich depicted in the book would have had a chance to visit the exhibition there, or buy photography (which was, given their reaction to the chapter dealing with their world, unlikely). Yet again Woods wanted to bring the work to a larger audience in the place he had spent so much time looking at, in fact working and living in:

“I really wanted to bring the work back home. So I started looking for funds and for a feasible way to exhibit my work in Haiti and get the book available for Haitians. I wanted to have the entire production of the book and exhibition done in Haiti.”

Getting it done posed considerable challenges such as, of course, funding, but also getting a Creole translation done, and making everything happen in Haiti despite the regular strikes, blackouts, and paper shortages – all that in way that would allow selling the book in Haiti for less than 10€. Given I own a copy of LETA, as the Haitian version is called, I’m not sure I share the photographer’s sentiments about it:

“The book is far from perfect. It is an experiment on many levels. The cover, when you open it up is also a poster because Haitians love to put posters up in their rooms. […] The book was printed while I was putting up the exhibition, so I could not be at the printer to see what they were doing most of the time. Some of the photos are very badly printed, and the quality changes from one book to the other…”

For a start, I’ve actually seen quite a few on-demand books printed in the US that look considerably worse than LETA. The printing in my copy isn’t so bad at all. That aside, a photobook’s form needs to truly be centered on what matters the most, and not necessarily on making a perfectly collectible object. Seen this way, LETA‘s production is about as perfect as State‘s.

In addition to producing LETA, Woods decided to show the work in Haiti as well, deciding to do an open-air exhibition on the Champ de Mars, the main square in Port au Prince, Haiti’s capital:

“This is where the presidential palace is (or what is left of it after the earthquake), where the military would parade, where the protest rallies take place, where there were thousands of tents after the earthquake, and where now hundred’s of Haitians just come for a stroll, have an ice cream or buy books from the street sellers. There is a long high brick wall on the square that is the enclosure of the university of ethnology and that seemed to me the ideal place.”

The resulting exhibition featured 25 prints, each roughly 10 by 10ft, glued to the walls. Volunteer students from the university helped make it happen. It’s probably fair to say that the results surpassed all expectations:

“Hundreds of Haitians would stop and want to see the photos before we had even finished putting them up. Each new photo generated groups that got in extremely animated debates, praising me or accusing me of the worst crimes. Soon it was not about me, but about Haiti, the State, the NGO’s, the evangelicals, the Americans, etc.”

Wishing to have as many people see the work as possible, Woods organized radio and TV interviews, plus coverage in newspapers.

“But I also asked 10 of the most respected Haitian painters each to reinterpret one of my photos and we made billboards with the paintings and placed them at crucial intersections around the city. So we were really getting the art in the streets! We managed to convince the police to close the road to the car traffic the day of the opening and I got a pickup full of Prestige, the Haitian beer, that was distributed to the people that had come. It was obviously open to everybody. No VIP’s. The book was for sale with the street vendors. We had received the first copies from the printer only that morning! A female rara carnival band came and played and it was the most thrilling artistic experience of my life.”

You can find the local coverage, and some of the public’s reactions here, here, and here (these articles are all in French). This video, produced by a local newspaper, gives you an idea what things looked like (it’s also in French only; but you want to watch it even if you can’t understand the language). The images in this article are photographs taken during the production and exhibition.

With these projects Paolo Woods has shown that contemporary photography can reach out beyond the narrow confines it usually finds itself in. There is a lot to be gained from doing so for all parties involved – those in the pictures, left out from the world of photography for economic, political, or cultural reasons, and the photographers (and writers) themselves who can find new, usually welcoming audiences. Thus, it won’t hurt for many photographers to look beyond their own navels, beyond the world of galleries, photography or photobook fairs, or dedicated photobook shops to get their message out.

Today’s photography market probably is probably unsustainable: there are more and more photographers, while the numbers of collectors and galleries aren’t expanding in nearly the same way. What is more, there are too many photobooks being produced for a market that’s hardly growing. Looking for new audiences thus is essential. And while essentially spamming the internet with PR (on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc.) is all the rage, getting the work out there in its actual form, whether as prints and/or as books, reaching those who for obvious reasons might be interested – that is the challenge photographers might want to face.

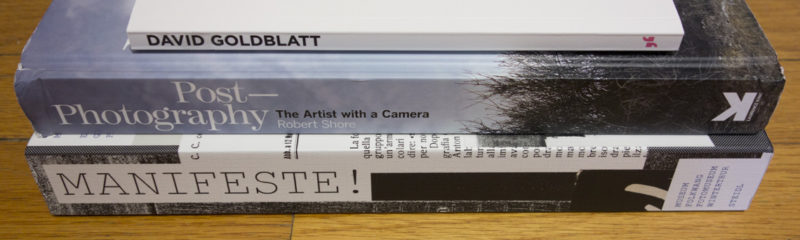

appears to have come at just the right time, to remind Europeans what those lessons are based on. Quite obviously, the First and Second World War are included, as are the Spanish Civil War, the various wars after Yugoslavia disintegrated, and there is the long conflict in Northern Ireland.

to learn a lot more about that).