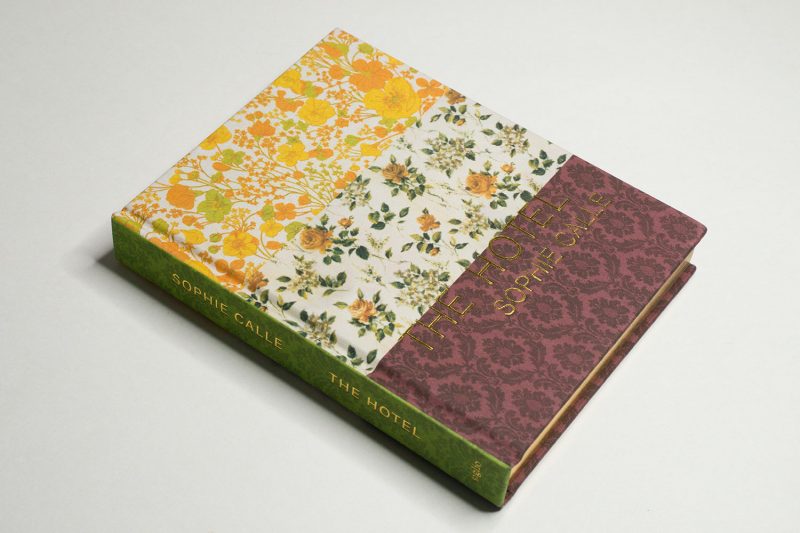

I don’t know what I was thinking. When I saw the announcement for Sophie Calle‘s The Hotel, I knew that I was familiar with the work, having seen it in Double Game. But I didn’t realize that that earlier book contained the entirety of it, meaning that when I received the new book in the mail and read “originally published […] in Double Game” I felt that I could (should?) have been paying more attention. The Hotel is a handsome production. But in a number of ways, it doesn’t quite reach the quality of Double Game: the latter’s paper feels like, well, paper and not like sheets of plastic, and the overall layout and design of the work — condensed, with the photographs being rather small — works in its favour as well. Thus, if you own a copy of Double Game, you don’t need this new book.

Maybe I remembered The Hotel from the earlier book only faintly because situated next to The Chromatic Diet, The Striptease, or Suite vénitienne, The Hotel feels weak. It lacks the droll artistic wit showcased in The Chromatic Diet. Unlike in The Striptease there’s absolutely nothing at stake for its maker. Lastly, The Hotel results from removing everything that makes Suite vénitienne so interesting, to leave behind a rather uninteresting core.

At this stage, I should probably note that in general, I am a big admirer of Sophie Calle and her work. If I had to describe Calle in just a few words, I would say that unlike any other artist I know, she has managed to tie her own vulnerability to her audience’s, implicating both (!) for their respective failures to lead a more meaningful life — and this means: a life less governed by artificial, societal conventions that only serve to suppress our shared humanity.

This description points at how I view any of Calle’s books (it is the book, after all, that is this artist’s perfect medium). My description is not intended to imply that the relationship between herself and her readers is always one of equals — quite on the contrary. A larger number of the artist’s works centers on the gender imbalance between men and women. (Last year, Alice Blackhurst wrote about the problem posed by the fact that Calle’s work is centered in a very bourgeois hetereonormative setting. That is a fair and timely commentary, which points in a different direction than the one I intend to make below.)

In many of her works, Calle subverts the power dynamic between men and women, at times directly or indirectly making the male gaze her subject matter. The Striptease documents work she did as a sex worker, work almost custom made for the late John Berger’s description of the male gaze: “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. […] The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object — and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.” (quoted from: Ways of Seeing) Suite vénitienne had Calle turn the tables by doing what (heterosexual) men typically do when they are “on the prowl”: she followed a man to Venice and tried to find out as much as possible about him. In The Address Book, she does the same with another man, albeit in a different fashion.

Referencing surrealist André Breton and the artists of the Situationist International, Stuart Jeffries writes that “traces of these avant-gardists’ loathing for bourgeois values, and their strategies to escape the tedium and uniformity capitalism imposes on those who live under it, are echoed in her work. […] Yet,” and this is where it gets interesting, “there is no sense in her work that there is a more authentic way of being. Her art is critique rather than search for utopia beyond the dystopia of today.” (quoted from: Everything, All The Time, Everwhere; Verso 2021) One might ask whether it’s an artist’s duty to do that, to “search for utopia beyond the dystopia of today.” I am more and more tempted to say that it is, but your mileage might vary.

Ignoring this aspect, there is the other major one, especially concerning The Address Book and The Hotel: privacy. “[P]rivacy itself,” Jeffries writes, “might be thought of as akin to property — a commodity amassed and defended most assiduously by the powerful, whose loss provokes the biggest outcry from those who have most invested in the existing late-capitalist order. From this perspective, which I suspect is the perspective of Calle, Proudhon was right to say property is theft, but he should have added: privacy is theft, too.” (ibid.)

When I read this against the context of Suite vénitienne and The Address Book (the context used by Jeffries), I found myself agreeing. But now that I’ve (re-)looked at The Hotel, I’m not so sure any longer. Or rather, maybe it’s the setup of this work that has me ask for something a little bit deeper. I suppose it’s one thing to have a woman artist pit herself against a man and openly violate what society has been taking for granted. Even decades after those works were made, they still feel relevant, mostly because as far as I can tell, the situation of people who are not straight men has not dramatically improved in my life time. In fact, completely new entities that didn’t exist forty years ago now replicate the very same power structures that would have been very much familiar back then (just look at how social media’s “community guidelines” cement the status of white, heterosexual men at the expense of everybody else). It is when that aspect falls away that things get iffy for the French artist.

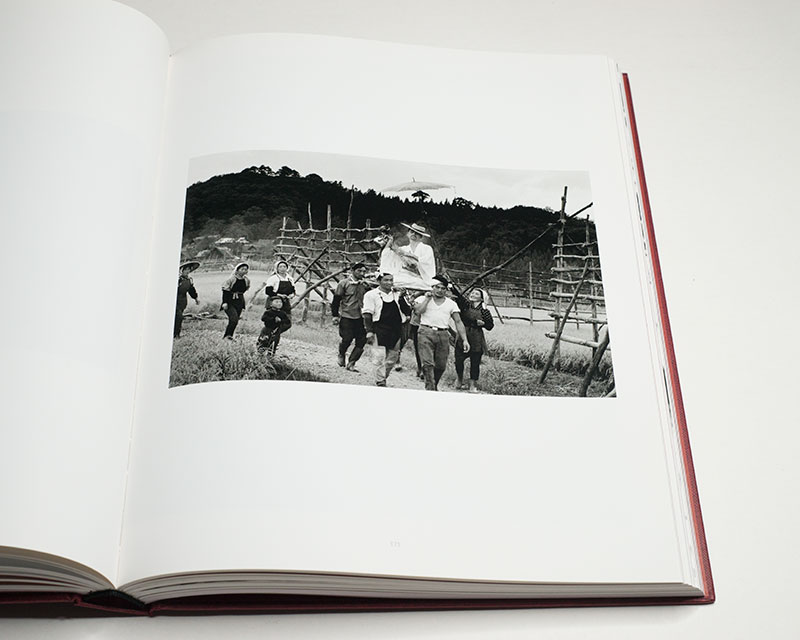

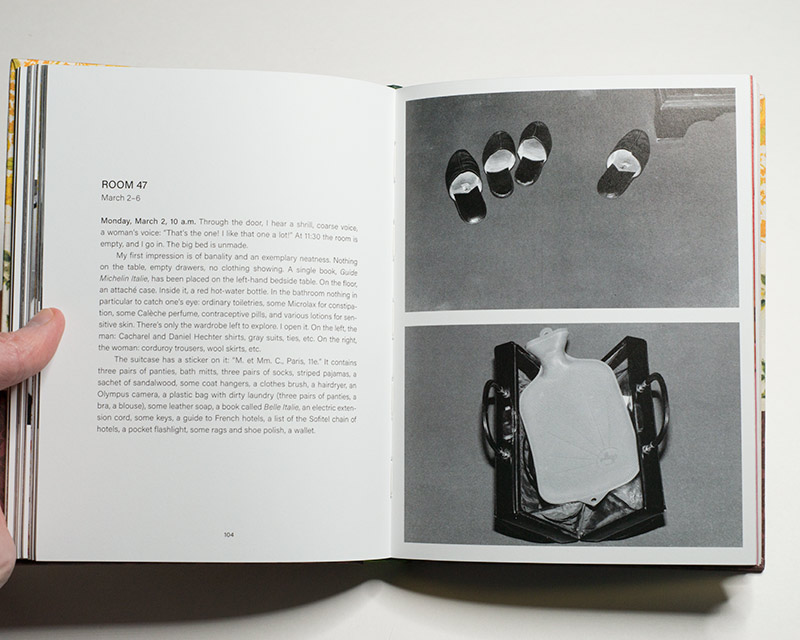

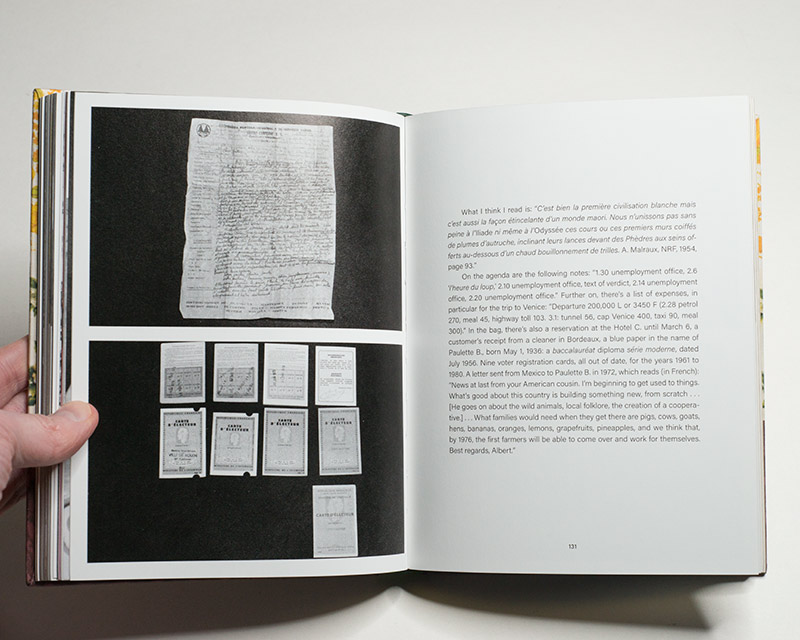

“On Monday, February 16, 1981,” Sophie Calle writes at the beginning of The Hotel, “I was hired as a temporary chambermaid for three weeks in a Venetian hotel. […] On the course of my cleaning duties, I examined the personal belongings of the hotel guests and observed, through details, lives which remained unknown to me.” The book’s structure is simple. Rooms are covered for the duration of (a) guest(s) stay. This begins with room 25, February 16-19, with a man occupying the room. Calle photographs some of his belongings and reads (quotes from) his diary.

This sets the stage for the rest of the book. One room, some period of time, a guest or, frequently, a couple staying in the room, the artist rummaging through their belongings, occasionally picking up spoken words. Ignoring the ethical problem of the rifling through personal belongings for a bit, one might imagine that this would result in at least something of interest. But no, for the most part, Calle encounters the mundane. As time passes and the reader makes her or his way through the book, s/he can’t help but feel how the artist herself got disillusioned by the paucity of the assembled material. As a reader, I found myself turning the pages faster and faster. That’s never a good sign for a book.

Of course, my reaction is based on an expectation (even if I wouldn’t necessarily want to admit this to myself): obviously, I’m wanting to come across some major revelation or at least some form of excitement. But it turns out that other people’s lives are just as ordinary as mine. In fact, I suspect that if someone were to rummage through my belongings in a hotel room, they might find more interesting material: the occasional rare art book, for example, a bunch of vernacular photographs or magazines picked up at some flea market… Or maybe I’m indirectly thinking my own interests are more interesting that other people’s? Obviously, I would not want anyone to rifle through my stuff any more than, I suspect, the people who stayed at that hotel in early 1981.

Still, I like my art to be on the subversive side, regardless of whether it’s the one I look at or the one I make. But what exactly is subversive in Calle’s endeavour? Part of what bothers me about The Hotel is that its equal-opportunity subversiveness, where each room is being investigated, regardless of who occupies it. It’s questionable how subversive equal-opportunity subversiveness really is: it’s not at all the same thing, but would we call a toddler in their “no phase” subversive? I think not.

Furthermore, the blanket invasion of privacy demonstrated in The Hotel has not aged very well in light of the drastic decrease of privacy afforded to us today. If I were to imagine a Sophie Calle going about her hotel-room work today, she might find out a lot more if she were to simply monitor the guests’ social-media profiles and paid a little money to get access to data stored by data-mining companies. Obviously, this is not to defend the fact that corporations have trashed our idea of what privacy means, and it’s also not to excuse the fact that many people share more on social media about their lives than is actually healthy for them.

It’s also where Jeffries’ comment about privacy fall short, given that he notes that a person’s ability to voice her or his displeasure about a reduction of privacy (a voice that in our societies is tied to wealth and status) says something about the general populace’s approach to the topic. If poor people (literally) can’t afford access to more privacy that doesn’t mean that privacy itself is a bourgeois entity — it just means that our societies are stacked in favour of the wealthy and powerful (more often than not, this includes photographers). Furthmore, unlike property, privacy cannot actually amassed. This is one of the few, relatively minor details in his otherwise excellent book where I found myself in disagreement with the author.

If, as Jeffries wrote, Calle’s art is indeed supposed to be the “critique rather than search for utopia beyond the dystopia of today”, then I don’t think that this idea applies to The Hotel: where exactly is the critique? There’s no utopia, and there’s no critique. What is there? I’m reluctant to spell it out: Instead, what I’m left with is what I’d consider an at best minor work by an artist that I have a lot of respect for, a work that might have been better served had it not been reissued.

I suppose that some pieces of art age differently than others. This bums me out, even as I console myself with the fact that there is all of Sophie Calle’s other work that I can (and will) still enjoy.

Sophie Calle — The Hotel (Siglio, 2021)