The first picture of (not by) Eikoh Hosoe in the recently released eponymous catalog of his work shows a middle-aged man one could easily mistake for a tourist who somehow had found himself in a very nerve wracking situation. The photographer is seen holding his camera tightly (and close to his chest), peeking at whatever he might be confronted with through the thick frames of his glasses, a bright cap adorning his head.

Three pages later, that same man is depicted in hot pursuit of a person in a kimono running across some field: his camera is now in front of his face, and he is being captured in mid-flight, his right leg high up in the air, as if to clear an invisible hurdle.

On the following page, the timid man is back, here in the company of some of Japan’s most celebrated photographers of the 20th Century: in a picture from c. 1974, Daido Moriyama looks like an aging hippie who is wearing a floppy hat indoors, Nobuyoshi Araki exudes his usual degree of perviness, Masahisa Fukase seems ready to get into a fist fight with the person taking the photo, Shomei Tomatsu and Noriaki Yokosuka have clearly seen it all and hide behind a cloud of cigarette smoke, and with his white shirt and dark tie (the typical salaryman’s uniform) Eikoh Hosoe looks like a bank teller or middle manager who somehow has stumbled into the company of this motley crew.

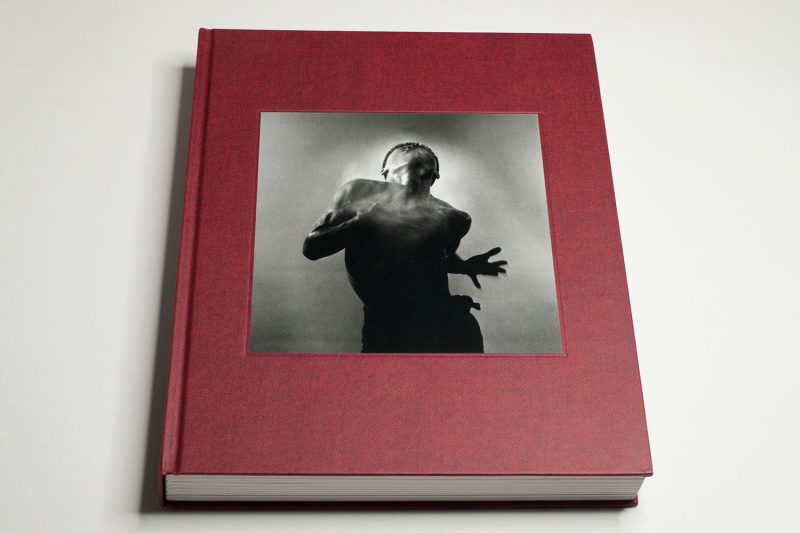

Who is this artist whose work is presented in expansive form in this groundbreaking catalog that has been edited by Yasufumi Nakamori, senior curator of international photography at Tate Modern?

Taro Okamoto, Artist, 1965

“A single bomb had killed tens of thousands of people,” Hosoe says, remembering the time when at age 12, he spent time in the countryside, to be safe from Allied bombs during World War 2, “my youthful bosom was filled with a powerful fear and hatred toward atomic bombs, with their capacity to concentrate such enormous force in a single bomb. Those feelings have remained, to this day, settling deeply in my heart. […] In 1968, I published the photobook Kamaitachi, a record of my memories from when I was evacuated during the war. That work, too, reflects at a deeply psychological level the impact of Hiroshima.” (p. 21) Who would have thought that what looks like a piece of dance-performance art in a very traditional Japanese rural setting had its roots in the photographer’s trauma, caused by World War 2?

Fittingly, Eikoh Hosoe begins with a chapter that contains the artist’s work in and around Hiroshima, showing, for example, photographs of peace demonstrations near the Atomic Bomb Dome (please note that here and in the following, the name in italics refers to the book). Hosoe’s life work would play out differently than Kikuji Kawada’s. But the beginnings speak of the shared trauma that both artists would weave into their work. In 1970, Hosoe would turn his photographs from Hiroshima into Return to Hiroshima, a book coauthored with Betty Jean Lifton. A Place Called Hiroshima followed in 1985. The books, he notes, were “written with young Americans in mind as our audience”. (p. 21)

Here, and in the following chapters in Eikoh Hosoe, the selection of the photographs evokes a somewhat different feel than the original books. In part, this is because any selection from a larger whole can only hint at how the work might function in its own context. Thus, the catalog’s viewer will arrive at a different impression of any of the different parts than when looking at the original books. I would argue that the selection and presentation in the catalog is more photographic than the books. By this I mean that more focus has been placed on the particular qualities of individual images.

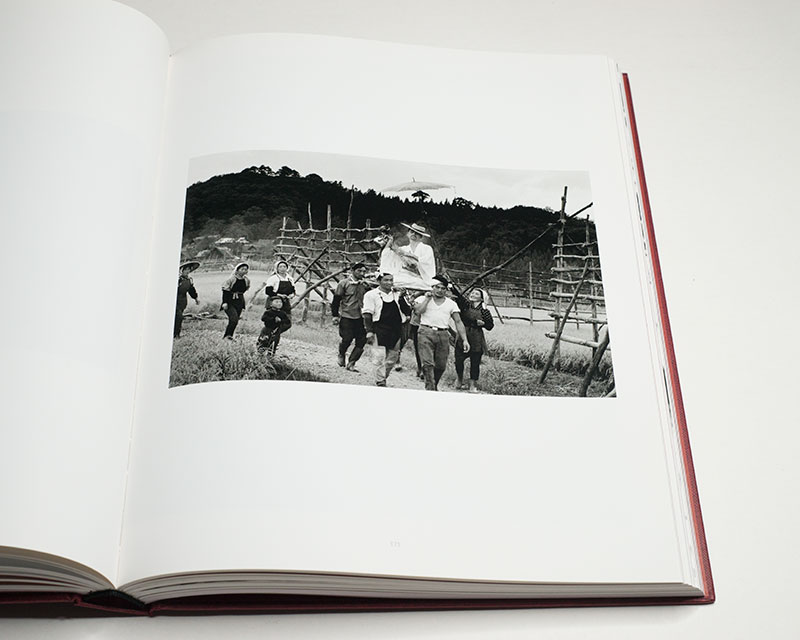

Kamaitachi #14, 1965

Consequently, a very clear picture of Eikoh Hosoe as a photographer emerges that, however, somewhat obscures the impact of the photobooks, whether it’s Return to Hiroshima, Kamaitachi, or any of the other ones. I do not intend to have this observation seen as a negative criticism of the catalog, though. To begin with, photobooks cannot be accurately presented in any other form as their totality. What is more, drawing out connections between separate bodies of work by an artist often is a lot easier when working from the photographs themselves. Anyone who is more deeply interested in Hosoe would be well advised to study both the catalog and his photobooks.

After a chapter entitled Early Work that showcases photographs taken in the early 1950s — charming work that betrays a competent photographer who has not yet found his own voice, the catalog moves on to Hosoe’s first claim to fame, Man and Woman. This was the first project that involved butoh dancer and frequent collaborator Tatsumi Hijikata, the man he is depicted as chasing after in the photograph I discussed in the beginning. After meeting Hijikata, Hosoe decided to “create a photographic drama” (his words, p. 87) in his studio, involving him and a number of other dancers. “However tiny a gesture”, the artists writes, “it constituted my only transgression against the era. […] a response to the shouts of protestors heard outside the studio: ‘Down with AMPO [the US-Japan Security Treaty]!'” This seems rather implausible, maybe even to Hosoe himself. He continues that “[m]ore than anything, I was consumed with a burning desire to explore ‘sexuality.'” (p. 87)

Man and Woman #20, 1960

Roughly ten years later, Hosoe would return to the theme depicted in Man and Woman with Embrace, inspired by Bill Brandt’s Perspectives of Nudes, the appeal of which has largely escaped this writer. Where Man and Woman manages to sizzle with transgression and sexuality, Embrace is little more than a very competent exercise in form, ultimately as limp as Brandt’s nudes.

Yukio Mishima, an incredibly talented and multifaceted artist who also happened to be a rabid nationalist, wrote the Preface for Embrace, which appeared after Mishima’s suicide. Eikoh Hosoe includes it and a large number of texts written by people directly involved in the work. These added texts contribute massively to the value of this catalog.

In Hosoe’s work, Mishima detects what he calls “an undercurrent of darkness.” “This darkness,” he writes, “is a characteristic element of Hosoe’s photographic artistry, as well as an isolation born from a rejection of salvation.” (p. 123) One cannot help but think that Mishima might have in part projecting his own thoughts onto his fellow artist’s work: could not his cartoonish pseudo-putsch and subsequent suicide in late 1970, many years after it had become obvious that Japan had embraced its democratic order, be seen as a similar rejection?

A few years earlier, Mishima had found himself in front of Hosoe’s camera for Ordeal by Roses (this is the English title used in the catalog; Killed by Roses is used just as widely). Hosoe photographed the writer in a number of settings with a large number of props, often verging into surrealist territory. “One day,” Mishima writes, “Eikoh Hosoe stopped by and whisked me away to a mysterious world. I had previously seen magical works produced by the camera, but Hosoe’s works did not suggest magic so much as they displayed a quality of mechanical wizardry, as he used this civilized instrument of precision to its utmost against civilization.” (p. 199)

Ordeal by Roses #32, 1961

Thus, the writer finds himself cast into a world that was “alien, contorted, derisive, grotesque, barbaric, and dissipated”. (p. 199) These words can serve as good criteria to divide Hosoe’s work into the artistically successful bodies of work (such as Man and Woman or Kamaitachi) and the ones that, like Embrace, while well crafted are little more than formal exercises. For me, Ordeal by Roses somehow unsteadily wobbles in between these two poles, which might be an editing problem more than anything: curiously, the more straight photographs are visually powerful, while the surrealist abstractions feel overwrought.

And then, of course, there’s the magnificent Kamaitachi, another collaboration with Tatsumi Hijikata that finds both men return to the area they were from to inflict photographic mayhem on the countryside and its unsuspecting inhabitants who ended up playing along (because it was, one must assume, the polite thing to do). Mishima called the work “humerous yet also cruel” (p. 123), and it’s not hard to see why. “I had a hunch,” Hosoe writes, “that if we went to his hometown in Akita I would be able to shoot his butoh as it had never been seen before.” But the photographer also describes the photographs as “a ‘record’ of my own ‘memories,’ both nostalgic and sad, of having been evacuated as a schoolchild during WWII.” (p. 155)

For Tatsumi Hijikata and Yukio Mishima, two such incredible artists in their own rights, to not only submit to Eikoh Hosoe’s lens seemingly without doubt, to afterwards praise the resulting work in the highest terms (“Eikoh Hosoe made me famous,” Hijikata wrote in 1969, p. 351) must mean that, no doubt, this particular photographer is one of the great Japanese photographers of the 20th Century. One can only hope that this catalog will serve to establish and cement that reputation outside of Japan as well.

Highly recommended.

Eikoh Hosoe; photographs by Eikoh Hosoe, edited by Yasufumi Nakamori; essays by Yasufumi Nakamori, Christina Yang, Eikoh Hosoe, Nobuya Yoshimura, Yukio Mishima, Shuzo Takiguchi, Tatsumi Hijikata, Donald Richie, Satoru Yusawa, Mutsuo Takahashi, Mamoru Maruchi, and Kenji Hosoe; 400 pages; MACK; 2021

Full disclosure: MACK is the publisher of my book Photography’s Neoliberal Realism