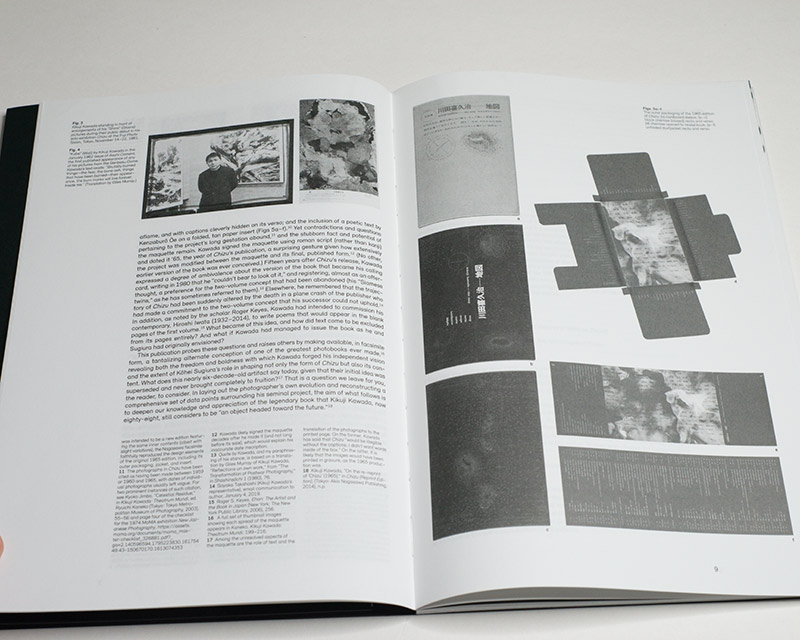

Japanese artist Kikuji Kawada‘s book The Map (Chizu in the romanized form of its original title) is widely seen as a landmark photobook. Published in 1965, there exist two recent reissues that both reproduce the original more or less faithfully, as a modestly sized book with a large number of gatefolds. But now, another version has appeared: the Maquette Edition. The book was co-published by MACK and the New York Public Library. With a long interview with the artist himself, and added scholarship by Joshua Chuang (Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Associate Director for Art, Prints, and Photographs and Robert B. Menschel Senior Curator of Photography at the New York Public Library) and Miyuki Hinton (an independent art researcher living in Tokyo), the publication serves to shed a lot of light on an artist who isn’t as well known and understood in the West as the fame of his book might make you think.

Spread from photography annual Sekai Shashin Nenkan ’62: Photography of the World (Tokyo: Heibonsha), showing photographs by Kikuji Kawada on the left and Shōmei Tōmatsu on the right. (Imaging by Yukinobu Kobayashi.)

The Map can only be fully understood when its context is taken into consideration. After all, it is one of a number of Japanese photobooks covering the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1958, Ken Domon published Hiroshima, which largely focused on survivors. Three years later, some of Domon’s photographs were paired with work by Shōmei Tōmatsu in Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document 1961. Five years later, Tōmatsu published Nagasaki <11:02> August 9, 1945. Both Hiroshima and Nagasaki <11:02> would be re-published by their authors in expanded/edited versions later. “I have taken around 12,00 photographs of Nagasaki,” Tōmatsu writes in the epilogue of the 1995 version of his book. “Fourteen years passed between the first two books, and fifteen between the second and the third. When so much time elapses — I grow older, accumulate so much more experience — my selection of photographs is sure to differ. […] it is like the buri (yellowtail), whose name changes as it grows. We call it inada when it is very young; hamachi when it is bigger; and buri when it is mature.” Tōmatsu’s approach might serve to help with the conundrum that the Maquette Edition poses for Westerners expecting just one — the definitive — edition of a book: it doesn’t have to be this way. As much as not any one version of Nagasaki <11:02> is definitive (collectors probably have different ideas), we can approach The Map the same way.

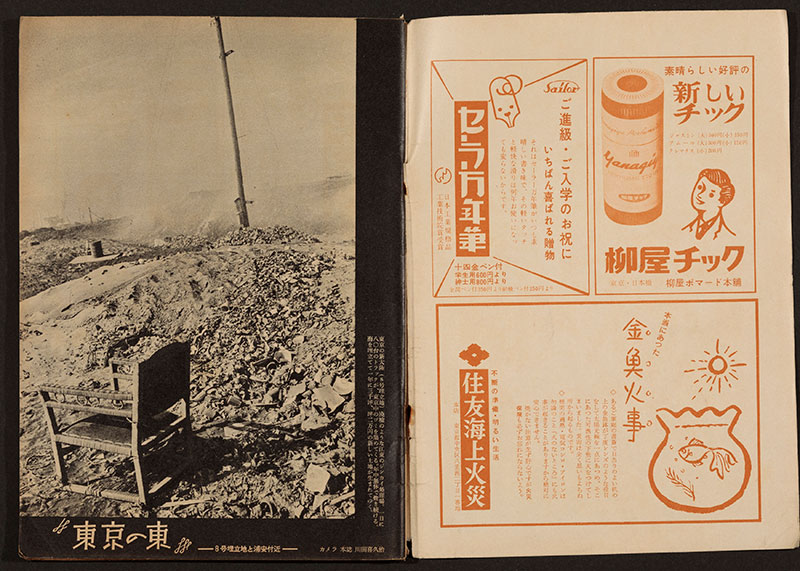

Spread from the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho (3/25/1956) with Kawada’s photographs in a feature titled “Tokyo no Higashi” (East of Tokyo) about a land-fill area in Urayasu, Chiba Prefecture. (Imaging by Yukinobu Kobayashi.)

In 1952, Kawada received the top prize for his very first submission to a contest in Camera magazine. As Kōtarō IIzawa outlines in his essay The Evolution of Postwar Photography, which can be found in The History of Japanese Photography (Yale University Press, 2003), Domon had been tasked to be the judge. In his role, Domon not only selected winning photographs, but also wrote detailed critiques of them. Furthermore, he engaged in an exchange with photographer Ihee Kimura on photo-realism, defining it as “strictly a realm in which only the objective truth in the subject motif is pursued, not the subjective image or fantasy of the artist.” As Miyuki Hinton outlines in her essay in the Maquette Edition, Kawada was persuaded by Domon’s modernist beliefs. “The topic of debate was whether photography should be concerned first and foremost with ‘realism,’” Hinton says, “but there was also debate on the definition of ‘realism.’” The discussions themselves are probably a lot less interesting in hindsight than the fact that they happened: they provided a fertile atmosphere for photographers attempting to understand what they were doing.

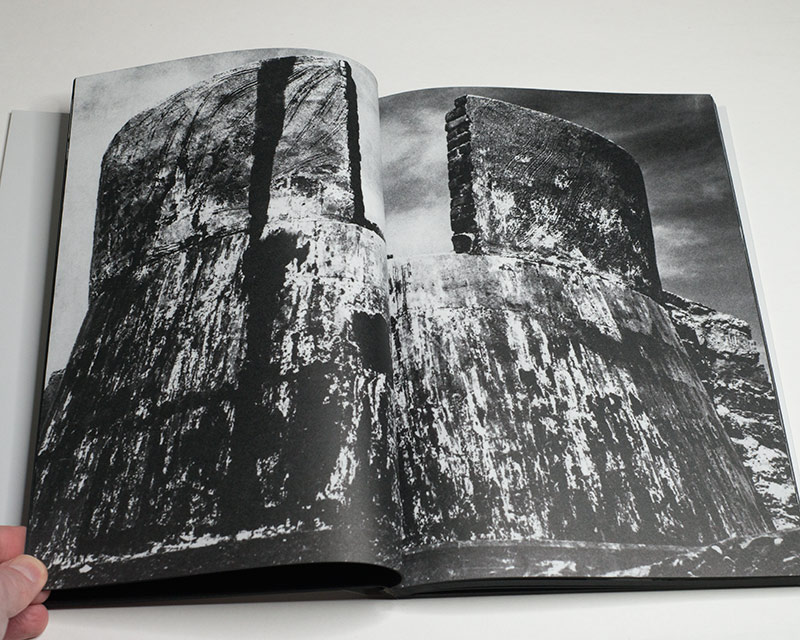

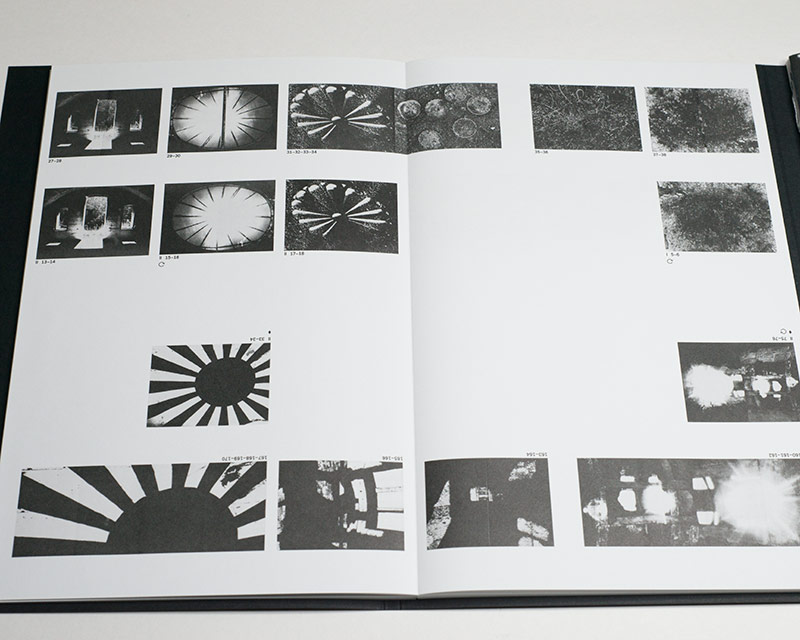

Spread from volume 2

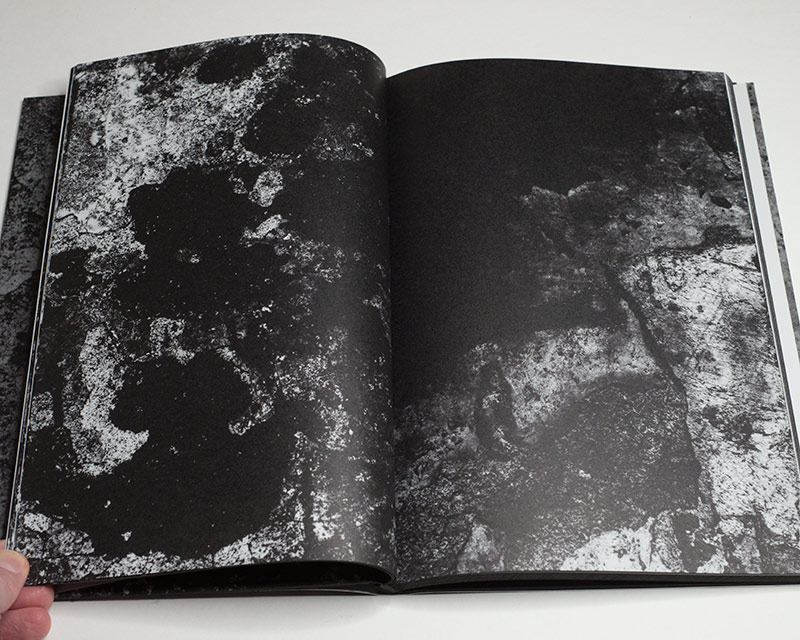

Originally emerging from a more realist position, like many of other members of his generation Kawada ended up moving towards a very different type of photography. In 1959, he co-founded a short-lived, yet influential group of photographers called VIVO. The group included Shōmei Tōmatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, and others. The Map reflects its maker’s artistic development through both the more straight photographs and the expressionistic abstractions. In the straight part (in the Maquette Edition its own book, featuring a white cover and referred to as volume 2), the influence of both Domon, the mentor, and especially Tōmatsu, a peer, can be felt. In fact, the imagery stretches from Domonesque straight work (such as an abandoned military concrete structure) to Tōmatsuesque pictures that often place the photographer much closer to his subject (such as a crumpled pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes) all the way to abstract imagery that would not feel out of place in the other book (volume 1). Even as the Maquette Edition separates straight and fully abstract pictures into two separate books, which seemingly serves to drive home their differences, there is a strong connection between them. This connection becomes more easily apparent in the one-volume edition. In the Maquette Edition, the contrast between two books amounts to encountering two different worlds: where volume 2 moves in and out of the terror of war and destruction, volume 1 immerses the viewer in a bewildering experience that reminded me of watching Nobuo Nakagawa’s 1960 Jigoku, a movie that includes depictions of hell. Of course, unlike in the movie the terror in Kawada’s work is only abstract. But that doesn’t make it any less terrifying.

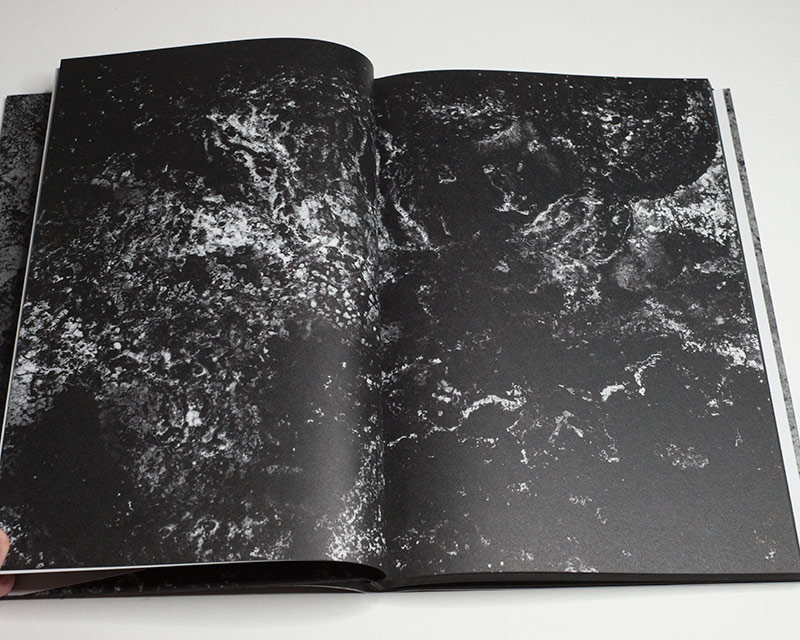

Spread from volume 2

The idea of the artistic genius who produces amazing art seemingly out of a vacuum might make for appealing narratives. However, the reality of art making typically is very different, with artistic genius creating a fusion of elements that are in the air, possibly working with and against ideas used by those before her or him.

In the interview in the Maquette Edition, Kawada notes that he spoke with art critic Shūji Takashina because there were no discussions in the world of photography about what interested him. “He is skeptical of discussions about what is real or not in photographic terms,” Hinton tells me, “which is why he seeks out different types of criticism. Takashina provided that in his observation of the images. Kawada says he looked at each as a ‘tableau,’ in other words as a flat image plane that contains an artistic expression and whose formal qualities are put into question. Not some idealism or opinion about what is ‘real’ or what is worth recording with a camera.” Hinton observes that the world of photography had a tendency to become “isolated from the rest of art society, compartmentalized, and over-reliant on the opinions of peers” (which, I’d be happy to argue, it still is, whether in Japan or elsewhere).

Art was not the only environment that provided Kawada with ways to approach his images. “Another area Kawada investigated in the way of criticism is that of the written word,” Hinton says, “as in novels, poetry, and literature in general. Literary circles had a more mature culture of criticism about abstract and expressive forms of art.” It’s possible that these types of references might feel like adding too many details to the work. But if one wants to understand The Map, it is important to see where it was coming from: the book ultimately has a lot more in common with a piece of art than with photography — something that Kawada spoke of very forcefully when I heard him talk about the book in Tokyo a few years ago. Consequently, even as it is a photobook, to judge it only by that medium’s terms will not do it full justice.

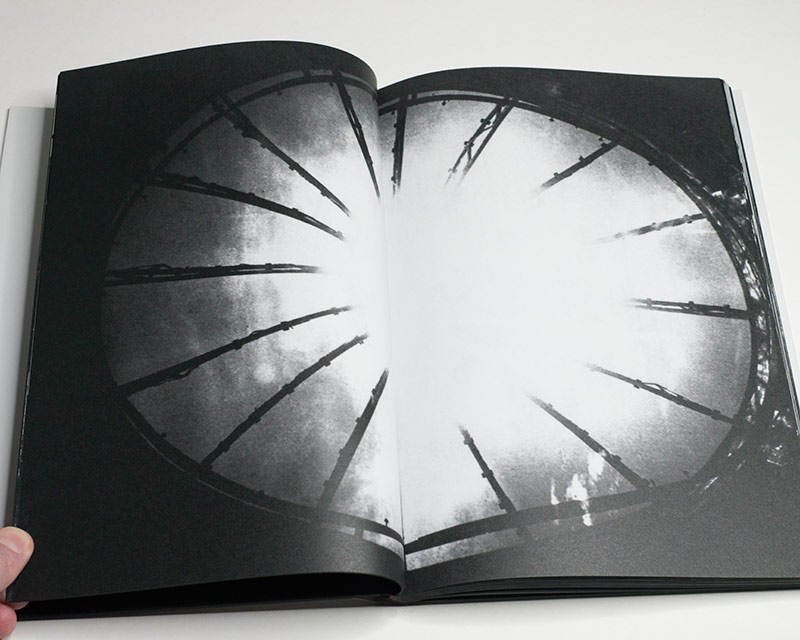

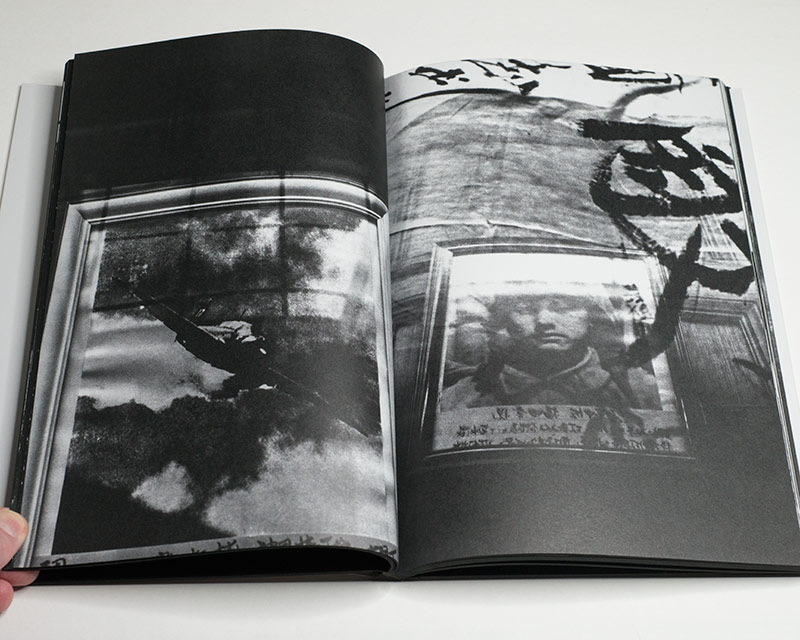

Spread from volume 1

Kawada’s earlier connection to his mentor is of importance. There also is “his background in journalism,” Hinton says, “which Domon primed him for.” “I credit him as the reason I made Chizu… We were very close,” Kawada describes his relationship with Domon in the interview in the book, “but I think he mistook our relationship as being one of apprentice and master. I never thought of it that way. I was sometimes referred to as the prodigal apprentice, though I never saw our relationship that way.” There is this: the psychology of relationships. After all, artists are human beings. To have one’s work defined in relation to a well-known other figure’s achievements cannot have been easy. At the same time, there is a form of artistic debt that is being paid off with The Map: Hiroshima had to exist for it to come into being.

Kawada was born in 1933. Speaking of his biography, the late German Chancellor Helmut Kohl spoke of the “mercy of late birth.” Born in 1930, he wasn’t old enough to end up in a combat situation at the end of World War 2. Kohl’s sentiment was (and still is) widely seen as glib, given that it conveniently ignored many other people’s experiences, regardless of whether they were German or not. But there is something interesting about the generation born in the early 1930s. Its members were old enough to grasp the reality of war in ways that children would not. At the same time, they were spared becoming an active part of the war, even as they might have had a passive role. Kawada was a member of that generation. Hinton’s background essay provides a lot of details. Kawada was “raised in Tsuchiura, Ibaraki Prefecture, where the Japanese Naval Preparatory Flight Training Program (known as “Yokaren”) was established during the war. In the final year of the war, […] several oral-history accounts given by former residents include stories of watching air combat; some recall walking for miles to lay eyes on a fallen plane and its captive pilot.” (p. 25f.)

Spread from volume 2

I was struck by the fact that I had heard similar accounts in my own life time. When I was in high school, one day and completely out of the blue, my Latin teacher (who must have been born in the early 1930s) told us how he witnessed a low-flying fighter plane attack a commuter train that he was traveling on at the end of the war. He saw a number of other passengers fall from the train after being hit by bullets. When I heard the story, I was around the age that my teacher was at that time. Ever since, I have tried to wrap my head around how one would go about processing such events. “Kawada’s own impressions of the time are detached in tone,” Hinton writes, describing an incident where he witnessed a US plane that “glided through the air so close to the ground that young Kawada could see the face of the pilot as its machine guns issued bullets, rapid-fire.” (p. 26) Kawada’s story and my former high-school teacher’s are very similar. I now know that trauma cannot be processed in simple ways. But I was struck by the fact that Kawada “has repeatedly denied any association between Chizu and the trauma of war.” (p. 26) Hinton concludes the paragraph dealing with this aspect by writing that when asked, the artist admitted that he was “unwilling to probe deeper behind those closed doors.”

Spread from volume 1

How could there not be a deep association between the book and his maker’s experiences? I asked Hinton about this, and her answer is worth quoting in full detail: “It seems to me that Kawada feels unable to pretend as though he can speak of the traumas of the war, because he survived the worst. He survived without being in the center of the worst experiences that fell upon so many people. That may be due to several factors. He was fortunate in that he didn’t live in a city that was completely destroyed. And he was a few years younger than the age at which he could have been enlisted or eligible to join the war. At the same time, he was growing up right next to that training center, not differentiating himself from those young men, young boys, who were employed. He believed the propaganda. Everyone believed the propaganda that this was a just war and that Japan was winning. He believed all of the hype up to a certain point. And then the war was over, he survived, and by the time he made the work was able to understand that any political stance is fraught with contradictions. It could be that because he has very strong principles he wouldn’t let himself speak about ‘the trauma of war’ or the ‘trauma of Hiroshima’ having been spared from it, and having moved on, living in a booming postwar world. It’s that proximity to the worst-case scenario that gave him this parallel view about life and about catastrophe. A Jungian Japanese psychologist named Kawai Hayao talks about ‘trans-personal’ experience. By Kawada not acting as first-hand victim or witness of wartime atrocity, he’s able to speak about a trans-personal experience. But once he pretends that he represents that trauma, he feels as though he’s betraying humanity.” The idea of the trans-personal experience can help us understand not only The Map, but also other pieces of art.

Spread from the study guide

Small section of the map of Chizu, comparing the two different versions

The value of the Maquette Edition lies in the combination of presenting the work in a different form than the one that is well known (yet hard to come by — copies tend to be prohibitively expensive for most people). A viewer might want to resist the temptation to decide which of the two versions is the definitive — or better — one (if you have followed my writing over the years, you probably realize that this is not easy for me, either). The writing in the form of the essays by Chuang and Hinton, a detailed artist’s biography, an interview with the artist, plus a large comparison chart that shows both versions side by side provide ample information to understand the artist and his work more deeply. Considerable research went into the making of the book. “I ended up collecting about 250 magazine articles with photographs and writing by Kawada between 1952 and 1966.” Hinton tells me. “This was based on my background in archival methods. I had studied archaeology and anthropology at Keio University as an undergrad and wrote my dissertation on applying archaeological methods to the analysis of vernacular photographs. I then learned, during my mentored internship with Ryuichi Kaneko at the TOP museum, that digging into the back-page margins of photo magazines sometimes yields rich information.”

The mystery of The Map remains. In both editions, the book exerts a strong pull on its viewers, making her or him face the abyss that humans appear to be so attracted to. Being able to place the work into its historical context allows for the making of connections and for an understanding of the man who produced it. Beyond that, meaning radiates out as it touches us in a number of ways. After all, we might note that this isn’t only a book about Japan: the nuclear bombs that killed hundreds of thousands of people didn’t come out of nowhere (I’m writing this article in a country that has so far been unwilling to face up to its past actions). If we want to have hope to step back from the abyss, we still have a lot of work ahead of us.

Kikuji Kawada: Chizu (Maquette Edition); two hardback books, each with a jacket, plus one paperback booklet with leporello fold; housed in a buckram bound hardback slipcase, protected in a printed cardboard mailer; bilingual essays (English, Japanese); 272 pages (total); MACK/New York Public Library; 2021