“Yaga is for me a loving manifesto,” writes Agata Kalinowska, “[i]t contains my ridiculousness. Ridiculousness is a language of friendship and intimacy. Sarah Silverman […] said that there is a gap in our lives which can never be filled. […] I think we need to do brave, stupid things in order for that gap in us not to go rotten.” (from the afterword of the book)

A little further down the text, the artist adds these lines: “When the desire for autonomy, for the freedom to choose and decide about our bodies and where we are going in life, encounters barriers in the form of fixed gender templates and oppressive cultural stereotypes, we witness the appearance of combative energy and violence, including economic violence.”

I suspect that these words resonate all over the world. But in a country in Poland, held in a double chokehold by a societally very dominant branch of the Catholic Church and by a neo-fascist government one of whose recent acts was to ban abortion, no doubt there must be heightened awareness of the very unequal power balance between straight men and everybody else.

At the very beginning of Yaga, a young woman is seen as emerging from the sea. It is dark, and the water is clear and calm. With her arms being outstretched by her side, it’s hard not to think of religious imagery. Given the mastery of the book’s editing and sequencing, this cannot be a coincidence. Its makers have a story to tell, and they do it with pictures (Kalinowska co-edited the book along with Łukasz Rusznica).

Over the course of the following pages, the viewer encounters a world that initially is only inhabited by women. It’s a world that is filled with harmony, compassion, and care, even as there are a few surprising — and for some viewers possibly shocking — elements (such as, for example, a used, bloody tampon). But none of these elements actually disturb the order of things — instead, the book offers an alternative world where what now often is hidden and frowned upon simply is out in the open and accepted, where queerness is an accepted part of life.

At some stage, there is a photograph of a young woman lying on the ground who is being tended to by two others. This marks the transition into the next “chapter”, which is filled with partying and its consequences. Here, men make their first appearances, albeit only in passing here and there. The world still is overwhelmingly female, and it is uninhibited: expressions of passion and sexuality are being allowed to run their course.

This section culminates in a photograph of a naked woman who is lying in a bed that is surrounded by colourful balloons. The photograph would have been taken horizontally, but here it is used in a vertical form. As a consequence, a powerful feeling of freedom and sexual ecstasy is conveyed.

But then, upon turning the page, the viewer encounters yet another partying woman — she is pulling up her top to reveal her bra (while hiding her face). Next to here there is a man leering at her breasts while pulling up his own t-shirt to reveal a hairy belly that clearly has been nourished with too much bad food and/or beer. Thus starts a section of photographs of men and all things male, a veritable horror show of crass, unappealing, and violent types.

A bottle is smashed on someone’s head, a younger woman sits uneasily next to an older man who for possibly all the worst reasons has his sausagy fingers running over the back of her neck, and in the middle of all of this, there’s a photograph of a statue inside a church showing some male priest or saint (who knows), his hands folded in the type of fake piety that is all too common in organized religion.

It all ends with a photograph of a young woman with a black eye. Given the nature of Kalinowska’s photographs — they’re essentially snapshots, comparisons with Nan Goldin are inevitable. There are many parallels, this particular photograph being one of them. The most obvious difference I would see between the two artists is that unlike Goldin, the Polish artist does not rely on the seductiveness of her photographs.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a marvelous book. But I’ve always thought that the fact that the photographs often are visually so pleasing is maybe its biggest shortcoming. I truly love the book and its photographs, but I feel that it makes it too easy to appreciate the photographs because of their inherent beauty. In contrast, Kalinowska’s photographs look and feel a lot more like actual snapshots to me. Consequently, I personally feel the urgency of Yaga‘s message more than Ballad‘s.

The final section of Yaga circles back to its very first, and the book ends with a number of portraits of young women. Here, unlike in Ballad, the future is entirely female; and the idea that despite their many flaws, men are simply a part of the world is being negated: no, they’re not. Bravo!

In many ways, this is a spectacular book that deserves to be seen widely beyond its native Poland. I already mentioned its very masterful edit and sequence (it’s so good that educators could use it in class). There are a few other little tricks that are being used, such as, for example, photographs that would go across the gutter being cut into two separate parts (I’m obviously partial to this trick, given that I used it in my own Vaterland), or the orientation switch of the photograph I discussed above.

I’ve written this before, and I’m happy to reiterate my point: Poland currently is becoming one of the main powerhouses of contemporary photography in Europe, with a number of locations other than Warsaw being very active as well. Yaga comes out of Wrocław. If you’re at all interested in the world of photography, pay attention to photographers in Poland.

Highly recommended.

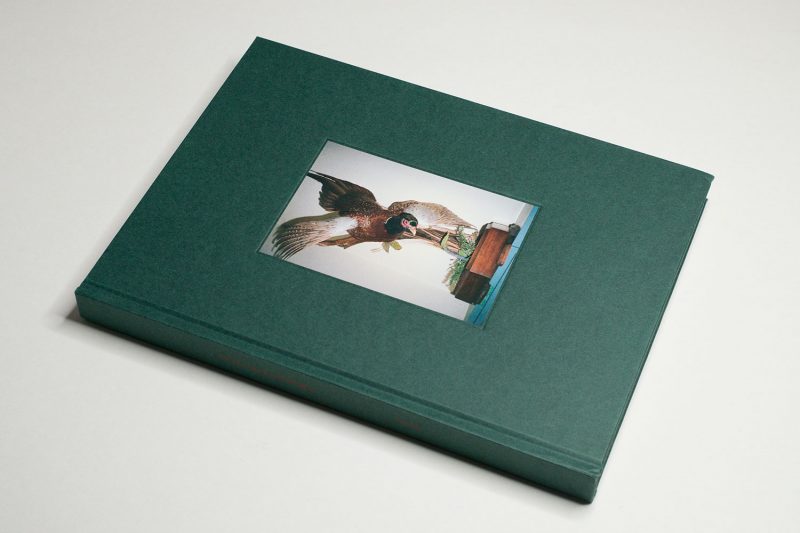

Yaga; photographs and text by Agata Kalinowska; 176 pages; BWA Wrocław Galleries of Contemporary Art; 2021

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 4.4

Ratings explained here.