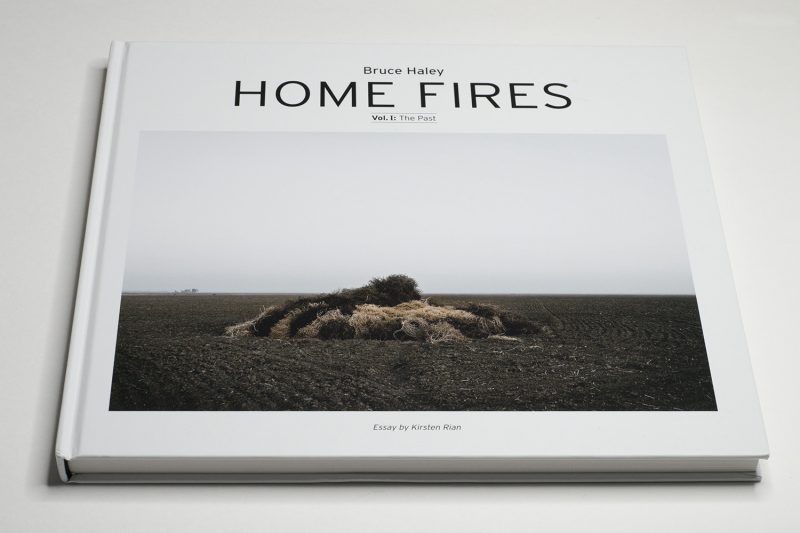

If someone like Laurenz Berges, who is less well known than some of his Düsseldorf Art Academy peers, came to the US and decided to photograph the San Joaquin Valley, I’m imagining that the resulting photographs would be similar in spirit to those in Bruce Haley‘s newly released Home Fires (Vol. I: The Past).

Unfortunately, analysis of what’s usually referred to as the Düsseldorf School of photography has mostly remained at the level of commenting on its preference of oversized prints, its often auction prizes, and the influence of its seminal photographers, Bernd and Hilla Becher. None of this gets at the essence of these artists, which in fact is more pronounced in those who aren’t as famous as Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, or Thomas Struth, artists such as Berges.

The term “deadpan” has often been used to describe the work. While I see the attractiveness of such description, there’s a major flaw, namely the assumption that those who make deadpan work are too cooly detached to have any emotional investment in their work. I think this is a terribly simplistic way of the relating an artist’s photographic language with both her or his emotional life and moral beliefs, and with what is in front of her or his camera.

Sadly, this idea is widely spread: drama, whether internal or external, has to result in dramatic pictures — lest the viewer is unable to come to any conclusions that are appropriate, given the scale of the drama. For example, you can find it behind many of the discussions around photography during the pandemic. I don’t know where this idea is coming from. Having lived in the US for almost two decades, I suspect larger parts of it are driven by the sheer ubiquity of the country’s entertainment industry that has conditioned people into expecting neatly packaged and sufficiently dramatic morsels when dealing with anything that is out of the ordinary.

Maybe a much better way to describe many deadpan pictures would be to say that they’re analytically photographed: A scene isn’t merely seen (which when it’s done well already separates out an artist’s eye), it’s also carefully and analytically described. Such description pierces the heart in very different ways than when there’s visual drama. As a viewer, you don’t realise what’s going on until it’s too late (assuming you’re going to bring along the patience required to look, given your aforementioned conditioning).

Despite the book’s title, there are no fires in Home Fires (Vol. I: The Past). Whether in Australia or in the Western parts of the US, large, barely controllable wildfires have become a regular part of the news. But global warming is hitting us with a combination of effects, some of which make for visual drama while many others do not.

When Haley photographed the San Joaquin Valley, it was in the middle of a severe drought that lasted from 2011 until 2017. The less severe version is ongoing and accelerating. In combination with increasing temperatures, it’s going to be lethal for a region that has been — but in the long run is unlikely to continue to be — a rich agricultural region.

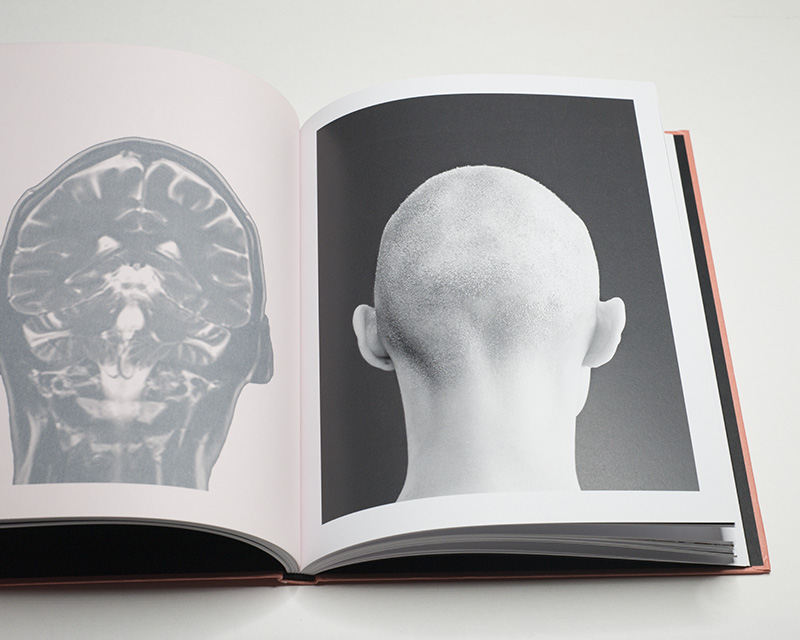

It’s not just the photographer’s approach that evoked Düsseldorf artists, it’s also the choice of season: Haley photographed in winter, when the Valley’s skies were grey or barely blue, resulting in the kinds of pictures that often would not feel out of place had they come from, say, Northern Germany’s flat plains. The winter light made for a great tool, resulting in muted, greyish tones that blend into each other and leave an overall feeling of dread, of something being desperately amiss. The photographs are in colour, but more often than not, they look or feel monochromatic.

Haley presents us with the view of a completely ravished land, a land that resembles the post-Soviet ruinscapes he portrayed before (however different his earlier approach towards those lands might have been). Even when they are not actual ruins, structures look as if they were. From the pictures, you wouldn’t know that there still is considerable life in this part of the world, however much it is now at threat (a threat that is likely to only get worse as all efforts to combat climate change have been rejected by roughly half of the country).

Seen that way, the pictures in the book are a description of what it already is for some of the time and a prediction of what the land will permanently become: an environment hostile to the creatures — we humans — who are responsible for the very hostility. In his introduction, Haley speaks of his family arriving in the area just before the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. A desperate wish to find more fertile grounds drove many people further West — ultimately resulting in the destruction of those grounds.

In all kinds of ways, Home Fires (Vol. I: The Past) makes for uncomfortable viewing. Like I said before, that analytical description of the land pierces your heart before you even know what happened to you. There’s no obvious visual drama; through the accumulation of a lot of photographs there is the built-up drama of something being very terribly wrong. Unfortunately, the Düsseldorfy approach will have some people hesitant to spend time with the book, but that’s their loss.

Climate change is hitting us on a daily basis. We’re just not capable of seeing or feeling it: everything changes so slowly. We can only see the most dramatic outcomes, which make for dramatic TV (or photographs): tornadoes, wildfires, floods, hurricanes, snow and cold in unlikely places… At the same time, these outcomes are impossibly difficult to connect with our own lived reality: what do wildfires have to do with driving cars that run on burning fossil fuels?

In the ravaged land depicted by Bruce Haley, there are hints of connections, such as when oil drilling stations are visible, or when there are artificial canals diverting the water towards a destination other than its natural one. But at the end of the day, it’s upon us to make the connections (and vote out the bums who still refuse to properly deal with the disaster that is going to hit the next generations much harder than us).

Photography can only so much. If either the dramatic pictures coming from the now ubiquitous natural disasters don’t change your thinking nor the accumulation of quietly desperate photographs in Home Fires (Vol. I: The Past) then, I’m afraid, you can’t be helped.

It’s just a crying shame that future generations will have to suffer the consequences of our collective can’t-be-helped comfort.

Home Fires (Vol. I: The Past); photographs by Bruce Haley; texts by Kirsten Rian and Bruce Haley; 144 pages; Daylight Books; 2020

Rating: Photography 4.5, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.8