Whatever you want to say about Instagram “Stories”, one account that does them really well is called Behind the Scars, a project by Sophie Mayanne. I think right now, they’re taken over twice a week, with a different person (often, but not always, a young woman) talking about some scars on their body and the underlying medical and/or mental reason(s).

As a man, I never had to worry about scars at all: if you had one, that usually was and still is seen as a reflection of some form of manliness (this never made any sense to me). Over the years, I’ve come to learn that for women (let alone someone not identifying within this set of binary choices), the situation is very different: there is the double whammy of scars being seen as a sign of weakness and of societal beauty standards that dictate how one is to present oneself.

As far as mental health is concerned, the “rules” change a little. Given mental scars are invisible — as is mental suffering — contemporary society still stigmatizes people dealing with mental-health issues to a considerable degree.

As someone who has been suffering from depression for decades, I know the kinds of blank stares one gets when talking about it: you can almost see the other person’s mental wheels going, to prevent them from saying something really inappropriate (btw, if in such a situation you start a sentence with “can’t you just…” to offer advice, that’s already not helpful — regardless of how well meaning your intentions might be).

In the Behind the Scars Stories, the connection between physical and mental health usually becomes very clear: physical trauma often triggers mental trauma, and having to conform to societal expectations only serves to compound the problem(s).

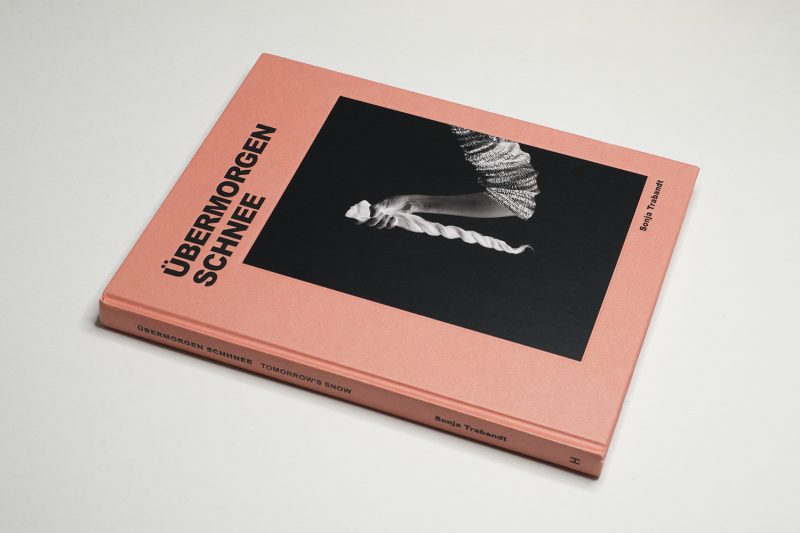

The same mechanism plays out in Sonja Trabandt‘s Übermorgen Schnee (Tomorrow’s Snow) [nb: the German translation of übermorgen is “day after tomorrow”; I’m sticking with the publisher’s English language title here). When her best friend, a young woman whose name is only given as “A.”, was diagnosed with cancer, Trabandt helped her deal with her experiences. At some point in time, when it felt appropriate to Trabandt to take pictures, this became a part of the process of dealing with what A. was going through.

I find the initial hesitation to bring in photography good for a number of reasons. Most importantly, it speaks of the deep care the photographer felt for her friend. Life and friendship are more important than making pictures.

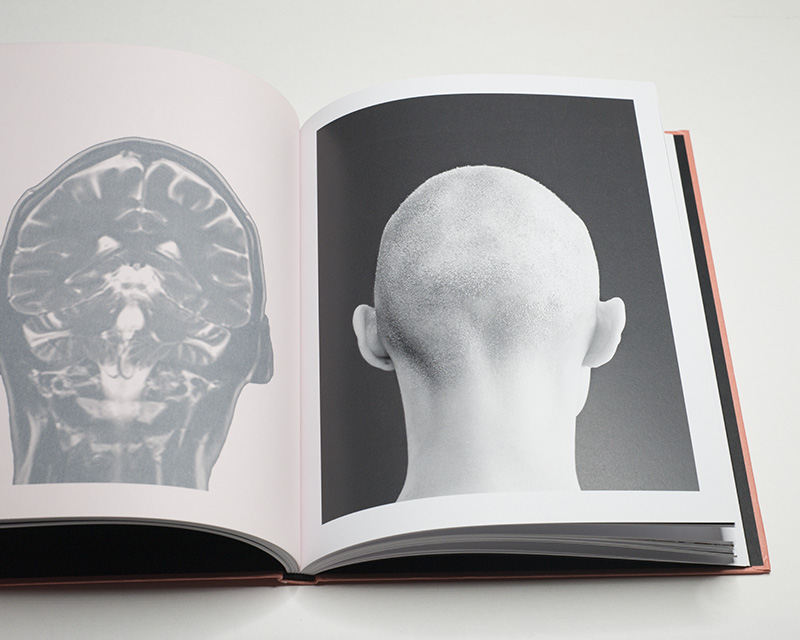

In the book, I don’t think as a viewer I would have picked up on anything missing from the pictures. That said, the turning of A. into someone who is completely anonymous — there are no direct portraits — removes me a few steps too far from that care and empathy.

It’s obviously easy for me to write this since I’m not talking about my own privacy. At the same time, I have been watching the Behind the Scars Stories, which dive deeply into personal matters without ever feeling intrusive: here, though, it is the persons themselves who decide what and/or how much to reveal.

At the end of Übermorgen Schnee, there is a longer text in which A. talks about some of the things that were most important for her. I found the text very deeply touching, in particular also because it talks about the severe depression the young woman plunged in after she was healed from cancer.

For the most part, text and images remain separate (there’s an index with thumbnails in the back). Text and images each have their separate ways of describing the world. In the photographs, a combination of still lifes, landscapes, and staged/arranged images, the main topic — cancer and all of its consequences — is very clearly communicated.

While A.’s scars are all internal, there was one other bodily factor which not surprisingly took on supreme importance: the loss of hair caused by the chemicals flushing through the body. I was aware of this aspect of cancer treatment, yet the way the book makes it a focal point (which is later reflected in A.’s writing) is very effective and — despite the often a little bit too formal and staged nature of some of the photographs — very touching.

A photograph that shows A. lying on a bed in a fetal position while cradling her own bald head is deeply affecting. Roughly thirty pages later, there is another picture from what looks like a similar point in time that shows one side of the bald head, a hand near the ear and one eye almost peeking into the frame. The deep sense of vulnerability and hurt couldn’t have been communicated more effectively.

Near the end of the book, there are ample photographs from a later joint trip by A. and Trabandt (the text makes this clear). I can’t help but feel that the photographs don’t convey the importance that the trip might have had for the two of them. But the addition of images full of sunshine and joy provide a good ending for the book — after a long period of physical and mental suffering, all is well.

This might sound like such a trivial conclusion in written form, but it must have been so deeply felt by the two people involved in the book, the photographer and her close friend, A.: all is well again.

The book’s penultimate picture shows A. lying on a bed, and the viewer can almost make out her full features. Apart from the two other photographs I wrote about earlier, this is the picture I respond most strongly to. Like I wrote, I understand the reasons for the anonymity. But the photographic anonymity comes at a price, with some of the artifice removing the viewer a step or two from the urgency of what’s on view.

Dealing with photography always involves some form of trade off: you can have some things at the expense of others — both photographically and in a larger sense. You’ll have to make decisions, especially if you’re trying to tell someone else’s story. Up until now, these decisions have been mostly driven by photographers, resulting in the consequences that have now become increasingly contested.

A recalibration of photographic approaches thus has been long overdue. In the end, we all can only gain from photography not always being done at the expense of those who find themselves in front of the camera. As viewers, this will inevitably force us to deal with our own expectations and preferences — it’s about time we realize that as viewers we are part of the very context photography operates in.

Übermorgen Schnee [Tomorrow’s Snow]; photographs by Sonja Trabandt; texts by Sonja Trabandt and A.; 136 pages; Hartmann Books; 2020

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.5 – Overall 3.6

Ratings explained here.