It’s now about a year into living with the pandemic in my neck of the woods. Roughly the same time span applies in many other parts of the world, excluding China, which experienced its outbreak a lot earlier. If you would have told me before that we would collectively experience a major event, my prediction would have been that we’d see the emergence of a large sense of solidarity. I am not sure to what extent this actually played out.

Right away, it seemed clear to everybody in photoland that the pandemic would become a major topic for pictures. At some stage, there would appear the first bodies of work. Initial efforts had me a little disheartened: there are only so many pictures of deserted streets or people standing behind windows with hand-drawn signs I can look at.

Meanwhile, in the larger world of news photography there have been the (almost inevitable) complaints that somehow, there have not been any iconic photographs. Frankly, I don’t know where such complaints would be coming from, given a number of truly heartbreaking pictures have been made. Go Nakamura’s photograph of a doctor hugging an elderly patient in a Covid ICU expresses the most one can hope for, right at the edge where both photography and words can only fail.

Now the first publications with images from the pandemic are trickling in. One example is provided by Stil Leven/Still Life. In March 2020, the Dutch Droom en Daad Foundation commissioned six photographers from Rotterdam to the pandemic in their hometown. The project was overseen by Hanneke Mantel, and the contributing photographers are Loes van Duijvendijk, Marwan Magroun, Geisje van der Linden, Naomi Modde, Willem de Kam, and Khalid Amakran. What did they come up with?

Van Duijvendijk turned her lens on a locked down city, with only two living creatures in sight. One is a cat, and the other one is a vendor in a little outdoor stand that’s shaped like an orange. Without any customers present and placed seemingly lost in otherwise grey neoliberal architecture, the kitschy cuteness of the stand serves to re-enforce to what extent we rely on such devices to distract us from our otherwise drab existences.

Magroun documented essential workers some of whom at least initially received daily support in the form of public clapping. Remember those days? I suppose improved work situations and better pay would have been even nicer. But now we’re at the stage where neo-Nazis march against restrictions, and a bunch of people are publicly burning masks in Idaho. In light of all of this I’ve been trying to imagine how I felt if I were an essential worker. One can only hope pictures like Magroun’s will remind people of the fact that many others literally risked their lives to keep things running.

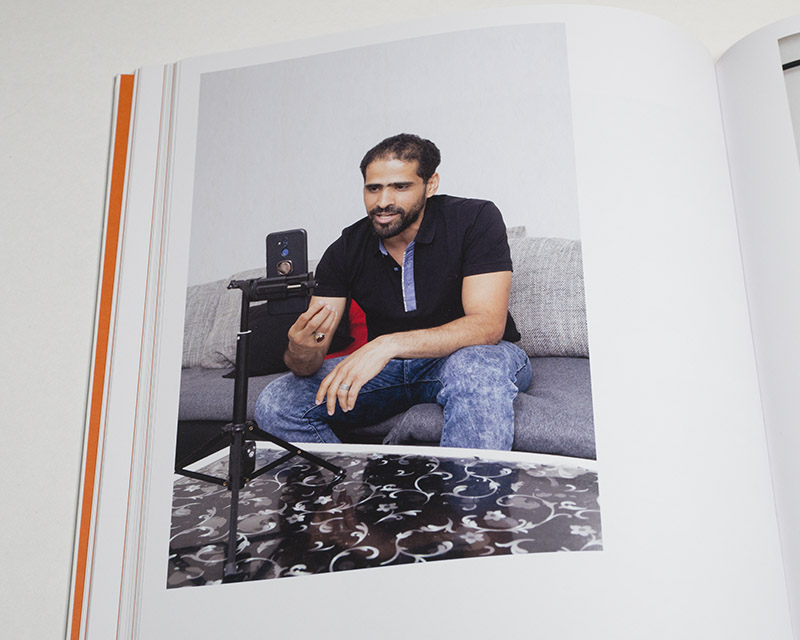

Van der Linden’s photographs centre around a single person, a human-rights activist from Yemen who got separated from his wife and young son (they’re both still in Yemen). The pandemic has been especially hard for the most vulnerable people. This group not only includes essential workers or poor people, it also encompasses people who had to or have to flee poverty and/or persecution: migrants. These pictures here show how much we all have in common. One can hope that they allow us to realise how much good might arise out of more solidarity.

Modde portrayed a number of families with young children in their homes all over Rotterdam. The pandemic has been very difficult for children and parents, and Modde deserves credit for picking up on this so early. There are only so many things photographs can convey. But the overall sense of being lost in one’s own home, having to deal with computers as interfaces to the outside world, comes across strongly.

De Kam produced maybe the most poignant photograph in the book (which is on its cover). It shows a hand that places a glass of orange juice and a slice of cake on a plate on the floor, reaching in through a door that’s barely open. Before the pandemic, we might not have easily come to the conclusion that we arrive at now: there is only one reason why one would not interact with a person in the same household. The text indeed informs the viewer that the photographer’s partner was infected with the virus, and they were unable to be in the same room. It shudders one to imagine this same drama playing out in countless households.

Lastly, Amakran made portraits of a number of Rotterdammers and asked them to write some texts for him. These are reproduced as handwritten notes next to the photographs (an English-language translation is shown right next to them). The notes are mostly banal, but that’s what makes them so poignant: even without a sick partner in the house, for many of us life has become a silent drama, in which worries about one’s health and livelihood (job) aren’t exactly helped by the aforementioned anti-mask protesters (not even to mention neoliberal politicians who’d rather save their precious economy than actual people).

I don’t know whether we still want to look at pictures from the pandemic when this is over. I’m sure I personally don’t want to be reminded of the virus. However, as I mentioned above, there are various things the pandemic has reminded us of, namely how living under neoliberal capitalism has eroded our sense of solidarity, our sense of being able to see other people for who they are (instead of seeing them as means to an end).

Thus, we should be looking at photographs made during the pandemic. As a broad collection of topics, made by and covering a diverse group of people living in the Netherlands, I think that Stil Leven/Still Life will be placed in the company of older books that documented a large-scale disaster (Mantel mentions the 1953 De Ramp photobook, which showed that year’s disastrous flood).

Stil Leven/Still Life; photographs by Loes van Duijvendijk, Marwan Magroun, Geisje van der Linden, Naomi Modde, Willem de Kam, Khalid Amakran; texts by Hanneke Mantel, Wilfried de Jong; 116 pages; Hannibal Books; 2021

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.