Like many cities, São Paulo was supposed to become a different place than what it has become. Flying into it for the first (and so far only) time, I was struck by its sheer size, its gigantic sprawl (it’s the 12th largest city in the world). With the plane approaching the airport, I would cross a sea of apartment towers, being unable to make out what I was looking for, the city’s center. But there is a center, even though it would take a local guide, Felipe Russo, to show it to me on the ground.

In fact, Felipe had shown me the center in his photographs before. But somehow, I had been unable to understand the clarity of his photographic vision. In part, I believe this was because of the kinds of expectations that I had brought to the work, not having been exposed to cities so radically different from, say, New York, London, or Berlin.

At the risk of simplifying (and being at the mercy of my memory), there had been plans to build a city whose civic life would not be dominated by cars. People would deposit their cars at certain locations (we’ll come to that in a bit), and then they’d roam the city center on foot. Many of the modernist buildings erected to that end were still around, and to visit them was to enter a real world of wonder. As is the case in so many cities I’ve seen (the most radical exception being Tokyo), things have fallen into disrepair while they’re still being used.

With Centro, Felipe had shown me what this looked like, combining cityscapes with modernism’s detritus and the various contraptions or constructions visitors and/or workers would erect for a short time. Walking around in the “set” that he had used for photographs, I realized that these photographs had a much larger documentary component than I had anticipated. And they spoke of the atmosphere of the place, where nobody seemed to care all that much about things needing a coat of paint or some repair as long as there was life to be had.

São Paulo’s cityscape was interesting in its own right, because I was able to see the city as a city — and not as a canvas onto which corporations would plaster oversized posters to advertize the wares and life styles they wanted to sell (São Paulo has banned public advertizing). Instead of ads there would be paint splatters on the previous blank sides of buildings: artists would leave graffiti or, where easy direct access was not possible, they would hurl balloons filled with paint.

It was easy for me to miss a few buildings that were different. Here and there, Felipe pointed out, there were these towers — buildings without windows that had been built to house the cars people were supposed to leave behind before entering the city center. They were rather massive automated garages, where you’d deposit your car, and machines would stash it away.

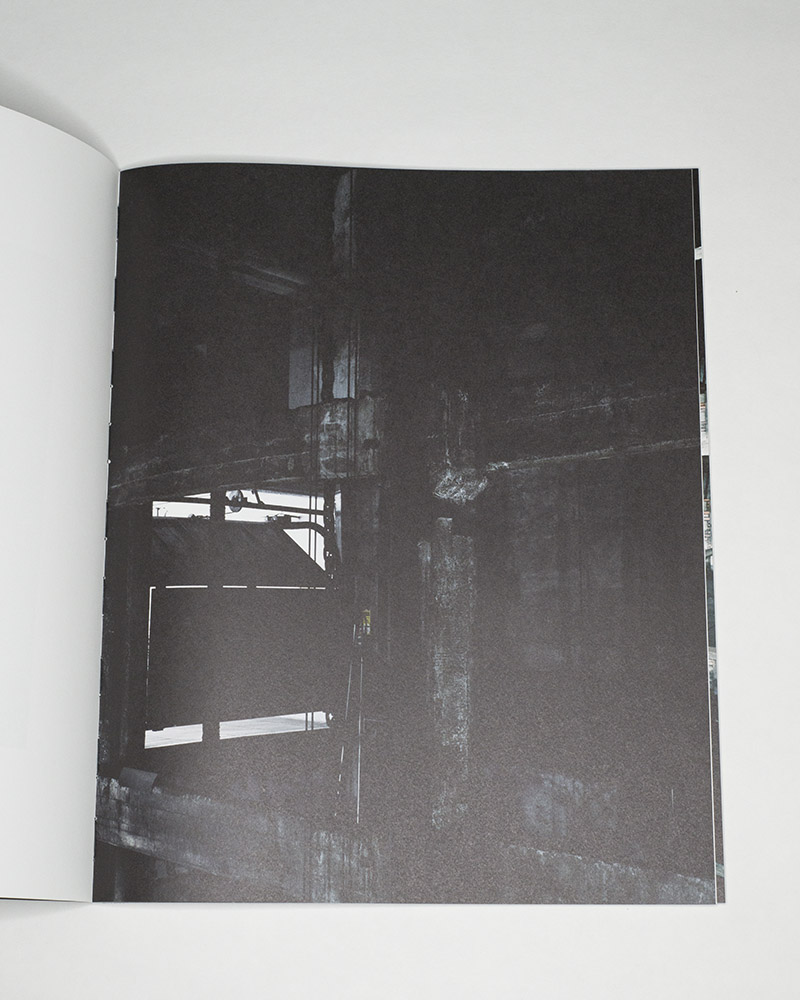

Felipe said he was photographing them. In fact, he was photographing in their bowls. How or why he would do that I had learned not to question. I couldn’t imagine entering what I thought would be rather dark and dank spaces with a view camera to make pictures of… what?

Garagem Automática now presents the photographs in book form. It’s an imposing monolith of a book. The size of the book helps to convey the surprising beauty of the photographs. In a sense, the interiors of those garages look the way one might have expected them to look — a dark sea of grey concrete and steel, with blue being the most dominant added colour. It’s not an inviting world. But it’s being rendered with a surprising tenderness, a tenderness that mostly derives from the photographer’s careful attention to details.

It is as if Felipe decided to bemoan the unfulfilled promises of the modernist ideas behind these garages — much like there’s a deep affection in his photographs of the central parts of his native city. I’m finding myself thinking that if he were German, his gaze would have been more relentless; it is easy to imagine this work fitting in somewhere with the Düsseldorf School at its peak. But where the Germans tended to ultimately focus on their tool’s cruel gaze, this Brazilian artist realized that it was his job — I’d even argue his duty — to steer that gaze towards something beyond the surfaces in front of the camera’s lens.

It is the sheer beauty of these photographs that has me think more about their maker than about the garages. Somewhere in these not very inviting buildings, Felipe found beautiful photographs — not looking for forms or description (as valid as that might have been), but for beauty. The last photograph in the book is my favourite: it shows three levels of some garage (well, four but the lowest one disappears in darkness), three concrete layers on which grime has been accumulating for years. The image shimmers in grey and black and white and blue, and the light falling in from somewhere helps describe the rough surfaces.

I suspect that most of what I know about these garages’ background is not going to be communicated by these photographs. How could it? But there always is that final step to be made when in the presence of art: whatever it is that stirs us in a piece of art, even if it’s “just” its beauty, points at something else, at a larger truth or idea that the artist wants us, her or his viewers, to connect to. Here, it is these parking machines that were intended to help bring about a more human city.

Now left to only fulfill their most immediate function, the almost three dozen automatic parking garages around the center of São Paulo have become the city’s tombstones for a modernism whose maybe naive promise has not been fulfilled.

Garagem Automática; photographs by Felipe Russo; text by Erik Mootz; 64 pages; Bandini Books; 2019

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 4.2