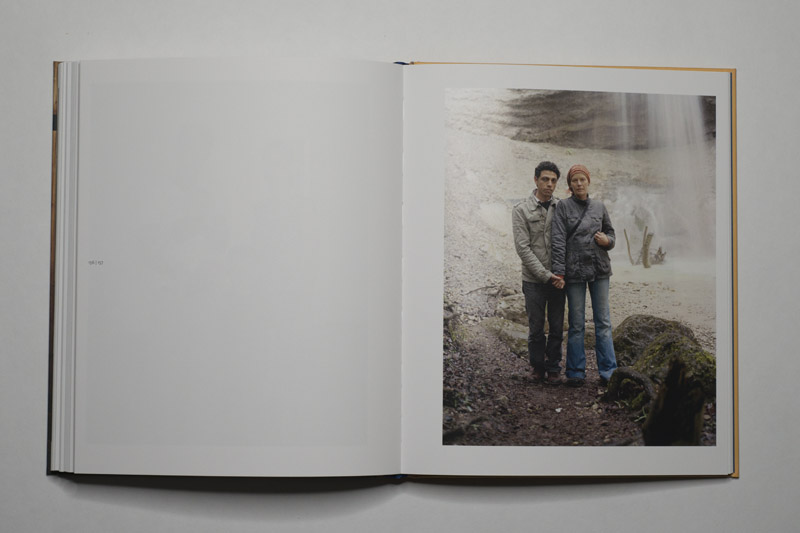

If you pay attention while looking through Andreas Mader‘s Days, Life, you’ll notice that the same people appear in different photographs. Change is imperceptible at first, but then someone is pregnant, and someone else is holding a baby. Time, in other words, is passing, and as it passes it does the things that it will do to all of us: if will age us and those close to us, and it will pull others in close while letting some of those previously close fade into the distance.

In a nutshell, that’s the book, chronicling the photographer and close family and friends over a period of thirty years through mostly portraiture. I’m sure this description will inevitably remind people of Nicholas Nixon’s Brown Sisters. The big difference, though, is that Days, Life is full of life in a way that the Brown Sisters project simply is not: the approach is just so radically different.

Consequently, with the Brown Sisters, the viewer will always look at photographs first, whereas here, s/he will mostly go straight to those portrayed. The rigidity of Nixon’s approach simply makes it very hard to get beyond the sheer tenacity of seeing the project through over four decades (at least for me). In contrast, in Days, Life it is not just those portrayed that are aging, it is also the photographer himself, especially in the very beginning. At some stage, the photographs look and feel a lot less candid — and it is this shift itself, which I feel adds a lot to the work.

Of course, I’m writing this article as someone who can look back to over five decades of life (note that depending on circumstances, the verb “can” usually gets replaced by a variety of other ones, such as “has to” or “will” or whatever else). I don’t want to make the assumption that my experience is common, but I’d like to think that life presents itself in different ways as one goes through its different stages. There are those points in time where one realizes that one ought to pay closer attention to what one is doing (either for the benefit of others or, usually, oneself, or, as can happen, both).

Looking through the book, I think I associated this shift in the work with that idea — and it’s really just the process of writing these words that has brought me this clarity. Ideally, after all, photography is life. And it’s so easy to do — all you need is a camera (which now comes as part of every cellphone) and the willingness touse it without thinking too much. That’s why large parts of Instagram are still so great, namely the ones of “ordinary” people sharing their life or rather those bits they deem and insist on being sharable.

That’s also why so many “professional” photographers are so bad when they’re on Instagram: they look at the pictures first, only to then (maybe) consider what they show — that is, after all, what you’re taught, that’s how you talk about pictures, that’s how 95% of all theoretical writing about photography approaches the medium. So they don’t make pictures for Instagram, they make pictures that they think look like pictures on Instagram.

In obvious ways, Days, Life is not what you see on Instagram. What Mader demonstrates, though, is how with a “professional” approach you can get at photographs that are life — photographs that not merely record life, but photographs that transmit life, that transmit everything that comes with life.

That shift that I spoke of above comes with another one, namely of those portrayed becoming aware of their own role in the pictures. Obviously, they all must have known about what Mader set out to do — if they didn’t know in a very specific way, then at the very least they must have realized what being in yet another photograph might mean — for them as much as for someone looking at a picture. This shift is hardest to describe in words, in fact it’s not even clear what is being gained from doing it. It’s simply best for the viewer to look her/himself.

All of this combines to one of the most touching, poignant photobooks I’ve seen in a long time. I couldn’t say that I’ve learned anything about those portrayed, I couldn’t even say that I have become interested in them — after all, they’re strangers. But their portraits, taken over such a long time span, have forcefully reminded me of what it means to be alive, and while I don’t know anything about them, I’m seeing their own coming to terms with the passage of time.

One final (unrelated) comment. Days, Life was originally intended to be published by the late Hannes Wanderer‘s imprint. I’m very glad that after his death Fotohof stepped in as a publisher. This book is another reminder of Hannes’ uncanny ability to find neglected or unknown photography and to bring it to a wider audience.

Highly recommended.

Days, Life Die Tage Das Leben 1988-2018; photographs by Andreas Mader; 208 pages; Fotohof; 2019

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6