Thomas Weski is one of the most preeminent German photography curators. Working at the Sprengel Museum, Hannover, at the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, and at Munich’s Haus der Kunst, Weski has been at the forefront of photography in Germany and beyond. His exhibitions include Nicholas Nixon – Familienbilder (Sprengel Museum Hannover 1994), Robert Adams – What We Bought: The New World (Sprengel Museum Hannover 1995), Judith Joy Ross (Sprengel Museum Hannover 1996), William Eggleston, Los Alamos (Museum Ludwig, Köln 2002), Cruel & Tender (Tate Modern, London 2003; co-curator), Andreas Gursky (Haus der Kunst, München 2005), ClickDoubleclick – the documentary factor (Haus der Kunst, München 2006), William Eggleston – Democratic Camera (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 2008; co-curator), Photography Calling! (Sprengel Museum Hannover 2011; co-curator), and many more. Since 2009, he is a professor for curatorial studies at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst (University for Graphic and Book Arts), Leipzig. I recently had the opportunity to spend some time with Weski, talking about photography, and I asked him whether he would be available for an interview. Much to my delight he said yes.

Jörg Colberg: Let’s start with a question that I have come across frequently: Is there a difference between German and American photography? If yes, how can that difference be put into words? Are the Germans, let’s say, a bit cold, or is there something else that sets them apart from the Americans?

Thomas Weski: I always find it hard to view photography based on national characteristics. But I noticed that after the impulses provided by American photography up until the early 1980s contemporary photography was then developed further in Europe, both in terms of aesthetics and content. These days, things have come back together. In the area of “photography in the documentary style,” to quote Walker Evans, there now is a sort of international visual language, with a similar way of working when accessing reality and a common aesthetic. I would not call this a bit cold. It’s distanced and in the best cases analytical.

To simplify a little bit, I think contemporary German photography is less tied to photographic conventions than its American counterpart, and it uses a wider range of approaches. However, this heterogeneity is not being noticed abroad. Instead, German photography is reduced to the Düsseldorf School. Thankfully, under Peter Galassi MoMA’s photography department introduced very different positions over the past few years: From Michael Schmidt to Andreas Gursky to Thomas Demand. It would be very nice if other American institutions had exhibitions with contemporary German photographers, which, might possibly not be necessarily popular, but which would allow visitors to discover something new.

JC: Today, photography is more popular and widely used than ever. But many discussions are centered on the question whether the medium has come to an end, or whether there are too many photographs, or how one is supposed to deal with the flood of pictures. What do you think about the medium in this year 2013? As someone who curated so many important exhibitions, who knows so many important artists on a personal level, is it still as much – or maybe more – fun to deal with this medium?

TW: Yes, it’s true, photography today really is very popular. A little while ago, I was looking at a paper from around the mid-1970s, which dealt with exhibition spaces for photography. Back then there were exactly 41 spaces in Europe that exhibited photography either regularly or exclusively! This included not only galleries or museums, but also exotic locations such as state-owned or corporate exhibition spaces. Today, in Germany alone there are over 200 spaces.

But there are only slightly more than a handful of museums in Germany that deal with photography on a regular basis, meaning museums that collect, research, preserve, exhibit and showcase photography. So far, there is not a single museum in Germany that uses the climate-controlled storage of photography that I know well from American museums. The budgets to buy new work have shrunk to zero, and a culture of donations like in the US does not exist.

In other words, there is a huge discrepancy between the international recognition of German photography and the way it is handled and accepted as an equal form of art in its own country. That notwithstanding, I’m still having fun with the situation. But at the moment, I am not working for an exhibition space or museum, and thus I’m not subjected to the very strong monetary restrictions.

I don’t think that photography has come to its end; maybe it is in all respects past its prime, but as a way to deal with reality it still is a very valid tool. Photography offers and can construct a particular closeness to reality, and for me, this is unique and very fascinating. And photography is being developed further with each new generation of artists.

“To simplify a little bit, I think contemporary German photography is less tied to photographic conventions than its American counterpart, and it uses a wider range of approaches. However, this heterogeneity is not being noticed abroad. Instead, German photography is reduced to the Düsseldorf School.” – Thomas Weski

JC: Which contemporary bodies of work are you interested in right now and why?

TW: Right now, I’m very interested in the works by Stephen Gill, Annette Kelm, Christian Patterson, Alec Soth, and Heidi Specker to name five artists who are well established in their respective countries. They all believe firmly in something like a specific photographic quality, and they all often also refer to the history of photography. This reflection of the medium’s possibilities, combined with contemporary content and artists’ abilities to translate their capabilities into pictures – that I am very interested in.

But there are also young photographers, such as Arne Schmitt, who studied in Leipzig and who presented and published a very original body of work about modernity in post-war German architecture. This body of work really investigates the question of what public spaces in our cities mean – many of them were developed in postwar Germany in the 50s and 70s and they refer to certain democratic ideals – how and what the implications are concerning how people can be included or excluded. What all of these artists have in common is that I often don’t understand their work right away, that I maybe even initially reject it or file it away too quickly in some drawer. But they all pull me back and ask me to re-engage and to look more closely. The fact that these bodies of work initially refuse to be engaged in a simple and easy way makes them all the more precious for me, something I often find hard to put into words.

JC: How can one master the flood of images online? Is there a way to deal with it?

TW: I view this flood of images as a type of visual communication, which I look at and use, but which in the context of art has no bigger meaning for me. The physical presence of a printed photograph still has an enormous influence on me. It allows me to access a photograph in a sensual, even physical way. I could imagine that this approach is going to become more important for other people as well. The photographs stored on my cell phone are not going to be printed, and they thus remain immaterial. They are fleeting – like falling stars…

JC: That might be a good approach to classifying photographs, the fleeting ones and those that have lasting power. I am able to truly appreciate a good photographic print, but I am a little bit worried about connecting physicality and not being fleeting. In the arts, there is an increasing number of artists working with images from the fleeting domain, and those images gain relevance not just because they are being printed. Don’t you think the fleeting images might play a more important role in art? I’m sure a lot of people will not be happy about the comparison, but we already have Jeff Wall’s light boxes or Nan Goldin’s slide shows, and both aren’t that far removed from images on computer screens.

TW: I agree that images might become relevant not only in printed form. This has been especially true for journalistic photographs online. On the other hand: Who was able to see Nan Goldin’s „Ballad of Sexual Dependency“ as a slide show? In the context of art, non-fleeting images that can be viewed by larger crowds bring other ways of engagement with them, which then determine a certain viewing time, much like video or performance art. For me, that is too restrictive, and such „black boxes“ give me the horror. But there are always new bodies of work in this area that impress me, because they create an atmosphere that photography cannot offer. Usually, I’d prefer to see them in a well-equipped cinema instead of a museum, however.

JC: Let’s talk about museums. Under John Szarkowski MoMA did a series of trail-blazing exhibitions, which were designed to bring the medium photography closer to the public and which explained it. With time such exhibitions appear to have become more and more rare. In 2003, you curated Cruel and Tender at Tate Modern. Has the time of such exhibitions passed, exhibitions that critically examine and/or define photography? Isn’t there today a large audience for exactly these kinds of exhibitions, combined with almost an urgent need to newly examine and understand this changing medium? Or is it maybe simply a wrong idea to expect this from museums, and one needs to look elsewhere?

TW: These days, museums are subject to a lot of pressure to have exhibitions with many visitors. I could imagine that in Szarkowski’s days the numbers of visitors weren’t even counted… At the end of the 1990s, when assessing culture business considerations and interests became firmly established even in Germany. Such exclusively quantitative expectations are often hard to meet with arguments concerning quality, which deal with the educational mandate, renown in the arts and a willingness to accept a certain risk.

Right now, I personally miss exhibitions centered on the development of the medium photography very much. But unfortunately it is a fact that exhibitions focusing on one artist attract more visitors than thematic ones, because they can be more easily dealt with under marketing consideration, and museums shy away from risks. Often, curators in the area of contemporary photography shy away from exhibitions on territory that is not yet historically defined: You’re on slippery territory there. In the past, at various institutions I tried to work out a photographic discourse for a wider audience with big exhibitions, and I very much enjoyed the specific challenges of such an exhibition format.

However, the resulting publications often ended up being more important than the exhibitions, and I would also say that about Szarkowsksi’s projects, without comparing myself to him. It is noteworthy that when we talk about photography exhibitions – even excluding “Family of Man” – we talk about the catalogues, and the exhibitions and their displays don’t play a role. Why is there no book about the history of photography exhibitions? If I look at my generation’s calling to establish photography as an equal form of art, based on what we did I could easily challenge today’s generation to create new spaces or forms of engagement with the medium, physical or otherwise. If they exist, I’m not aware of them, yet.

“If I look at my generation’s calling to establish photography as an equal form of art, based on what we did I could easily challenge today’s generation to create new spaces or forms of engagement with the medium, physical or otherwise. If they exist, I’m not aware of them, yet.” – Thomas Weski

JC: I’d agree one hundred percent. I do miss museum exhibitions that thematically deal with the development of photography today. Given that monetary concerns have become so important for museums, and given we are often talking about books… Maybe the time for new critical engagements with photography in museums is over? Maybe we need to look for other areas and work with books or internet-based exhibitions? It would be a pity, after all, to let this moment pass – where photography is more popular than ever before!?

TW: I just don’t want to believe that the time of a critical engagement with photography at museums is over. That would mean that museums and curators would be unable to lead the discourse in this area today. But maybe most museums really are too caught up in their roles and with themselves, so that smaller and more flexible institutions could play a role. In just the same way how we do not focus students on the art market any longer and instead apply other criteria, there could be other locations – let’s call them producers’ galleries, which would have other organizations structures and other priorities than museums. Each generation creates its own infrastructure, and I think there is a potential here to give today’s dominant organizations a run for their money and to challenge their values – much like the extra-parliamentary opposition did in the 1960s. Maybe just like in the area of film there could be an independent movement?

JC: How do you view the medium photograph, which right now is immensely popular? Do you look at photobooks?

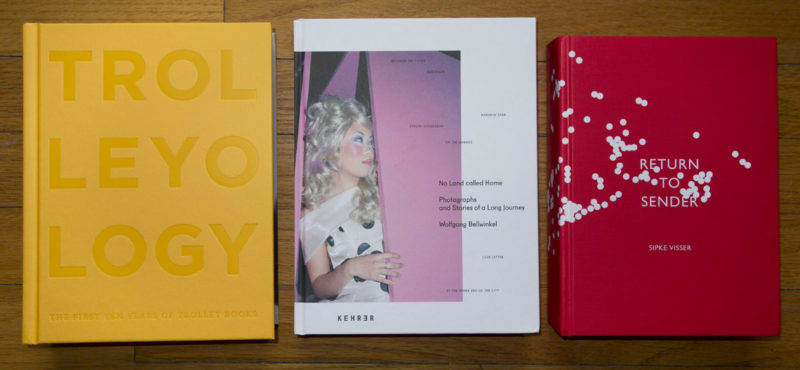

TW: I’m interested in photographers who develop different forms for presentation and publication. Earlier, I talked about the very small infrastructure for art photography in Europe in the 1970s. That was the time when I started to get interested in photography. There were hardly any exhibitions, but there were three book shops that sold photobooks. Along with magazines like “Camera” or “Creative Camera” (which still existed) the photobook for my generation was the most important way to get exposed to photography. To create your own photo library was thus extremely important. And it was an enormous privilege for a photographer to get published. It’s almost impossible to imagine this, but the very first monograph of a living post-war German photographer was published in 1978, in the form of “Situationen und Objekte” by Heinrich Riebesehl. For me, photobooks thus are their very own category of artistic expression, and they are as important as a carefully conceptualized exhibition – just in a different way! I see the work on a photobook as being closely related to curating an exhibition. Those are related activities, that also deal with dramaturgy, which to work in the long run requires highs and lows, which needs to “breathe” and to include different ways of engagement. Recently, I’ve been noticing how much I miss the practical curatorial work now that I teach and don’t create regular exhibitions. Photobooks instead of exhibitions could thus provide a real alternative for me.

That aside, I’m always very interested to see how artists translate their work into the different formats exhibition and publication. Some time in the 1960s, television replaced photography as a means to report the news, and it thus freed it for its artistic use. In much the same way, the ubiquitous availability of the internet and the flood of images might lead to the photobook now having not only a comeback after its first golden age in the 1970s, it might even get developed further in a variety of ways. This is very interesting, in part because now we have affordable ways of production.

The future of photography as an art might lie in the form of a hybrid, which finds very different expressions online, in an exhibition, and in a photobook, expressions that are connected and that refer to each other and push each other. This would be a dynamic model that I would find very interesting and in which the photobook would have a new role.