Verdigris is one of the words that is a lot less familiar than what it stands for. “A coating of verdigris forms naturally on copper and copper alloys such as brass and bronze when those metals are exposed to air,” the dictionary tells me. “Some American English speakers may find that they know it best from the greenish-blue coating that covers the copper of the Statue of Liberty.” I’m intrigued by the the word “some” in that sentence. Possibly that’s a rabbit hole that might not be in service of what I’m after here, namely to write about the new book by Harold Strak.

In a number of ways, Verdigris does not fit neatly into the current world of the photobook. It’s not topic based, and ideas of narrative are very far. Instead, it’s entirely concerned with photography itself.

Of course, there is a lot of work right now that focuses on photography itself. The vast bulk of that is what I think of as “Akademiefotografie” or “photography for the academy:” it’s made in academic settings (art schools) for academic audiences (peers and teachers, and then curators). It’s usually very good — and, at the same time, very soulless. Sometimes, I like looking at it. But mostly I don’t: photography for the academy is much too concerned with winking at those who are already in the know.

You couldn’t say this about this book and the work it showcases. In fact, it’s the complete opposite of Akademiefotografie. I have never met Harold Strak and I know nothing about him. But looking at this book I’m thinking that he really loves photography and what it does. You could cut out any of the pages from this book (not that I would encourage that) and hang it on a wall.

Obviously, you could do that with many other photobooks as well. But here, you’d look for a nice, understated frame — maybe something you’d find in a thrift shop, and you’d have something precious on your wall.

“Precious” is a very good word for the book itself as well. It’s published by Van Zoetendaal. “[P]hotography in print,” their website says, “must be optimally lithographed and printed so that it ‘becomes a new form of vintage.’” A new form of vintage — when you receive a book made by Willem van Zoetendaal in the mail, it usually feels as if you’re receiving something that has always been around, possibly to have been ignored or underappreciated until just now.

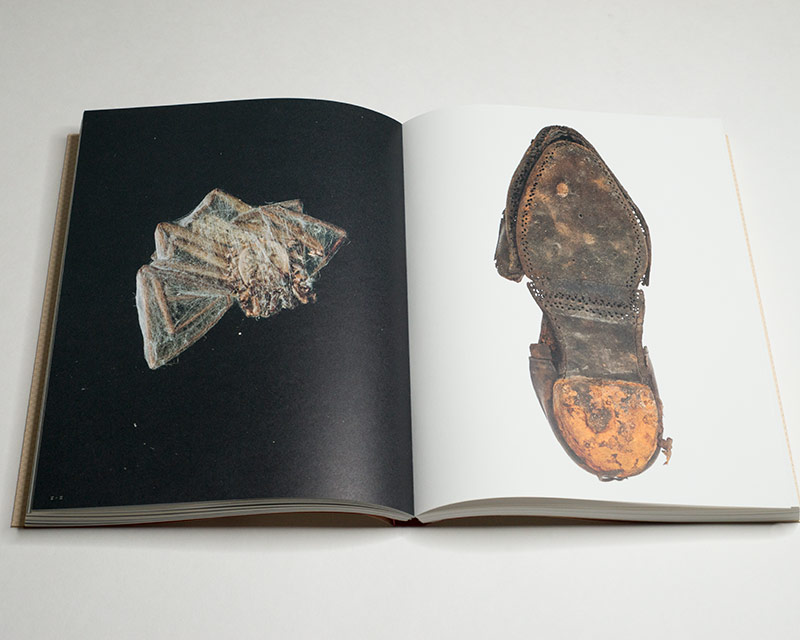

In fact, many of the objects depicted in the book were ignored and certainly underappreciated before they were photographed. Strak took pictures of 15,000 objects found during an archeological dig in Amsterdam. Those photographs made it into Amsterdam Stuff, which I reviewed here. Some of these pictures (a very small number of them, compared with the original set) are now included in Verdigris.

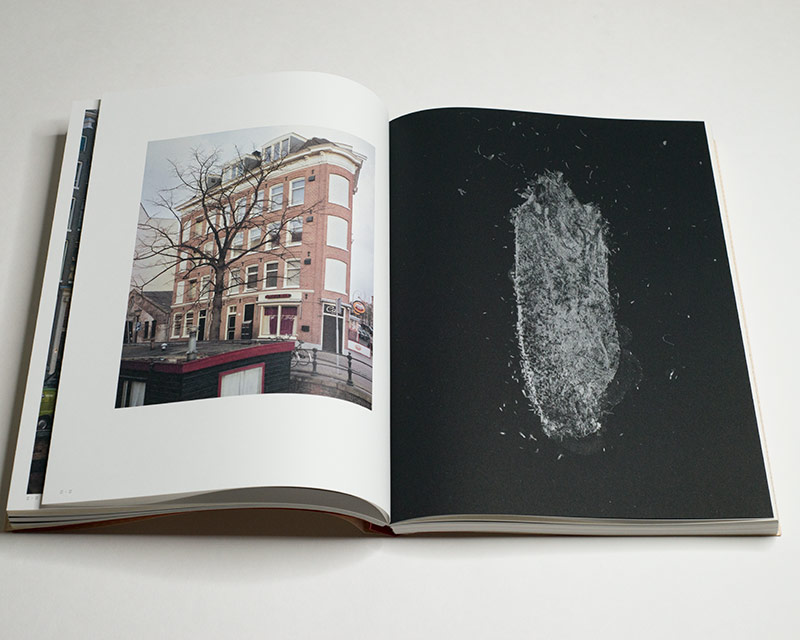

In addition, there are a number of pictures of Amsterdam itself: views of canals, of buildings, of trees (occasionally through what looks like a large studio window). I have been to Amsterdam a number of times, and I was struck to what extent these photographs transported me back, re-immersing me in this peculiar city’s atmosphere. Much like any of the cities that I enjoy returning to, my fondness for Amsterdam in part derives from it being attractive as a city only to some extent. It has its pretty corners, but there’s also the grime of life — the thing that makes a city interesting for me.

There’s something somewhat disconcerting about this book. There’s a difference between looking at a photobook and writing about it. But mostly, there is a convergence between those activities: to be able to write about a book, I need to look at it. During the process of writing, this looking can become almost obsessive, in particular if words fail to arrive. Books thus mostly lead me to the words.

Here, though, any time I pick up the book to get over a moment of being stuck, the photography doesn’t lead me to new words. Instead, it makes me think about something else. I’m not necessarily the biggest fan of art writing that focuses on its own discontent or its own process. So I’m finding myself slightly annoyed right now about doing it myself.

But I do think that the fact that this book resists being written about by me points at something: the photographer’s enjoyment of making pictures and the publisher’s enjoyment of making an finely crafted book translate into this viewer wanting to be immersed in it without having to think too much about what it all means, let alone having to try to convey it to strangers. I suppose that’s what I was trying to get at before when I wrote that the book “does not fit neatly into the current world of the photobook”.

Verdigris is a book of exquisite beauty where you’d expect none to exist. For example, in one spread, there’s a photograph of what looks like a flattened spider encased in a web (some other spider’s?) against a black background next to a picture of an old shoe, photographed to show its sole. Given this description, it might be hard to imagine that the pairing would be beautiful. But it is. Throughout the whole book, there is a lot of that kind of beauty.

What this all comes down to is the following. If you love photobooks, you should get yourself a copy of Verdigris. It combines the best of photobook production with a much needed reminder that there is joy to be had in photography. It’s the joy of seeing what photographs can do when they’re done well.

This strange combination of photographs taken by Harold Strak takes us deep into the photographer’s mind while making us think about how we connect to what is on view.

Highly recommended.

Verdigris; photographs by Harold Strak; essay by Vrouwkje Tuinman; 120 pages; Van Zoetendaal; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!