A few years ago, a wave of self publishing resulted in a very large number of photobooks produced directly by photographers themselves. Even as the wave turned into a fad, which inevitably broke, there were a few lessons to be learned. To begin with, despite the difficulties of publishing a book — it’s a lot of work and it costs a lot of money, there was a lot of excitement and passion swirling around the idea of the photobook. Unfortunately, large parts of that have now disappeared.

At the same time, in part because of the economics of it all, a lot of self published books were more modest: they often felt a little bit rougher (but in a good way), putting less focus on getting books printed in the most expensive place on the planet — and more focus on the books’ immediate impact. As you can probably imagine, the push back from the established parts of photoland ran along the lines of “there are too many books” (as if there were a way to determine the correct number of books) and “this looks like a zine”.

I’ve always struggled with the term “zine”. Interestingly, it has two uses by two distinctly different communities. In the world of subcultures, zines often are the preferred outlet, the idea being that if you’re part of that subculture, then you obviously have to make a zine (everything else would be “selling out”). I find the cliquishness of subcultures off putting. It’s actually not that different from the cliquishness of the established part of the photobook world, for whom the term “zine” is a snobbish way of dismissing other people’s work. Calling a book a “zine” is code for “this book is declassé”.

This situation doesn’t leave a lot of space for a much needed middle ground, especially given how vocal both sides are. However, I do think that there is an urgent need for more unassuming books: books that are photobooks but that also do not strive to be important art books.

There are two reasons why I think that way. First, many photobooks simply are too expensive. I understand that it’s expensive to make a book, and you have to make your money back. But especially these days where a lot of people in a lot of places are wondering how they are going to pay for a warm home this coming winter, an expensive art book might be the last thing on their minds.

Second, through its price, many photobooks attempt to telegraph their importance. This is merely another aspect of the neoliberal thinking in photoland that correlates price with quality and, by extension, with artistic merit. However, the reality is that such a correlation does not exist. It merely is psychology.

For aspiring photobook makers, this situation creates a huge conundrum. Given most photographers are part of the artistic precariat, making a photobook can result in enormous costs. Where are you going to get the money? How is it going to be feasible to make a book? Obviously, if you manage to get the costs down by opting for a simpler, more unassuming book then there are more options.

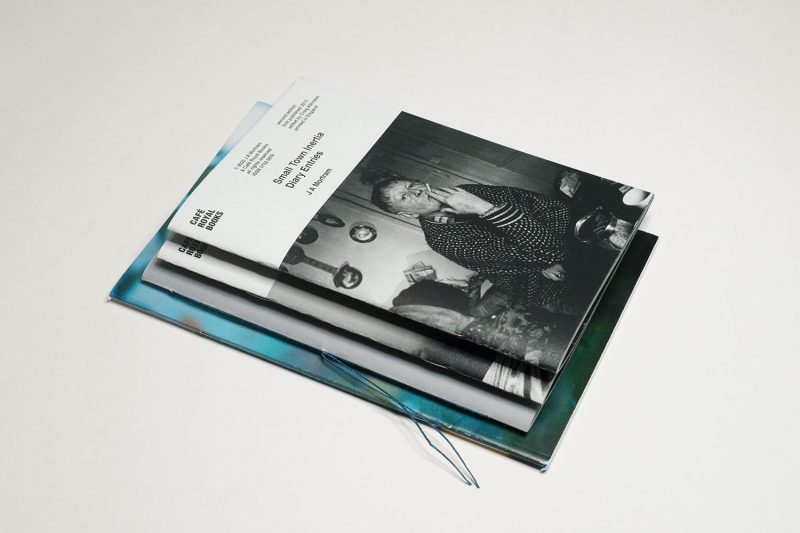

With all of this in mind, I here want to discuss a number of unassuming photobooks that recently arrived at my door step. The first two are from Craig Atkinson’s Café Royal Books imprint. I had been aware of Café Royal for a while. Given the strong focus on the UK, I haven’t been checking their publications regularly. There obviously is nothing wrong with a regional focus — quite on the contrary. As the books demonstrate, you can build a very solid and strong publishing branch that way. It’s just that I’m not British, so I’m basically not a member of their target audience.

But when J A Mortram announced that he was having two books published with them, I needed to have them: Small Town Inertia 1 & 2. Both books have 32 pages and are bound by stapling the sheets together. It’s a very economical way of making a book. Café Royal have honed down things very well: the printing is very, very nice, and the choice of paper makes the booklets more substantial than you might imagine.

As a result, these two booklets showcase Mortram’s work — possibly in ways that an elaborate coffee-table book would be unable to. Describing his subjects as living at the margins of society doesn’t sit well with me, even as I realize that that’s exactly the term used by many people. Instead, Mortram portrays the lived reality of a lot of people who for one reason or another aren’t well off enough to have a comfortable life.

The photography is stark and very affecting, something that I wouldn’t necessarily say about a lot of other photographers who train their lenses on Mortram’s subjects. I can sense the photographer’s compassion and empathy that is conveyed by these two books. Personally, that’s what I would want from this type of photography: it mustn’t use other people’s dire living circumstances to draw attention to anything other than what’s in front of the camera.

Douglas Stockdale is founder and editor of PhotoBook Journal. In many ways, it’s always good when someone who writes about photobooks is also involved in making them (whether their own or other people’s — you will note that quite obviously, I’m biased). The Flow of Light Brushes the Shadow follows the self publishing model of the photobook. To begin with, it looks and feels like many of the self published photobooks produced during the time I spoke of earlier (Stockdale does his own binding; here: a pamphlet stitch, which is similar to what’s used in the Café Royal cases, with thread replacing staples).

Because of the pandemic, I haven’t traveled since early 2020. Even as I miss traveling, I can’t say that I miss the aspect that is dominant in this book: the anonymous chain hotels that all look the same and that all exude the general neglect of very basic amenities that we otherwise take for granted. I also don’t miss airports and the hideousness of having to deal with them, let alone for hours and hours having to cram my frame (all 193cm of it) into a seat that’s made for an oversized toddler.

Given I’m a very private person, as much as I enjoy traveling, it also brings considerable stress. For me, the lack of privacy when traveling might be the worst aspect. It’s when the boundaries of my existence are defined by my own skin that I become most uncomfortable. The book immediately brought all of that back to me, even as I will have to admit that I cannot wait until I will be able to go back to Germany or Japan or wherever else.

At times, it feels as if Stockdale was trying too hard for his audience to get the idea of the book. I don’t think a statement needed to be included at the end so that people would understand the message. Furthermore, the very blurry images also are unnecessary, given that without them the idea of the book would be very clear. But now photobook aficionados can see Stockdale’s own work, which might put his own criticism in perspective (obviously, you can say the same thing about me).

Making a book is a good exercise for someone writing criticism. Seeing a book by someone writing criticism is a good way for an audience to see more of that person and where they are coming from.

This might be a generational thing. But I’m not sure Deadbeat Club is the greatest name for a publishing house. But what do I know? They sell books, coffee, and apparel. Regardless, recently I came across one of their publications that looked really interesting. I ordered myself a copy: Shiori Ikeno‘s Sado. In terms of production, the book is similar to the Café Royal titles: it’s a stapled pamphlet. It’s slightly larger, has more pages, and it’s in colour, making it slightly more expensive overall. But we’re talking about $15 vs however much £11.00 is. Neither one is very likely to break the bank.

I wasn’t familiar with this photographer’s name. The pictures were taken on one of the small islands that cluster around Japan’s four main ones. It’s called Sado Island and is located just across Niigata (which is north of Tokyo at the Sea of Japan). Many rural areas in Japan are now suffering from being populated by a heavily aging population, as young people leave or already have left for the big cities. Age and ageing loom large in Sado, with the main characters being the photographer’s grandparents.

You might say that I only know this from the publisher’s website; and yet I only know this for certain from there. The connection becomes quite apparent from the photographs. With the exception of the photograph on the back cover, which seems to be about something entirely different, the images exude a sense of quiet and of being in tune with the simple beauty of being.

In this recklessly busy world where the dominant ideology is one of “disruption” and of being constantly on the move, accepting the fact that the best parts of existence are far away from such nonsense offers solace. That is the lesson taught by this book.

Sado is simple and good, and that’s what photobooks should be: simple and good. Again, going beyond this simple format runs the risk of not doing the work any justice. Even as I could imagine maybe better choices for the paper stocks (in particular the cover feels a tad too plasticky), this understated book does all the right things.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!