The other day, I received a photobook by an up-and-coming photographer in the mail. Produced by one of those smart new publishers, it featured elegant, yet understated design in an altogether very charming and contemporary package. The inside, the pictures, could be described in just the same manner. The topic was one that a few years ago no photographer would have thought of or bothered photographing, and the pictures betrayed the photographer’s education at one of those cutting-edge European masters programs, with abundant colours everywhere and very stylish (and, of course, somewhat ironic) still lifes featured prominently throughout the book.

And yet! And yet!

Turns out it was just another book that I would put aside somewhat grouchily in the end. Something was missing. Something very specific was missing, yet again.

You see, ordinarily I’m no grouch. I’m merely employing the term because there is no equivalent of “hangry” for this case. (OK, OK, one is a noun and the other one an adjective. I know. But this is a blog, and you’re reading this for free. So you’ll have to excuse some stylistic freedom or sloppiness [your pick] here.) Or rather I would use the word “hangry” only for occasions when one is in fact in need of actual food. (I’m no grouch, but you don’t want to meet me when I’m hangry.)

But the sentiment I’m after is the same: In the book that explored its topic over pages and pages of stylish pictures there wasn’t a single human face to be seen, despite the fact that it actually dealt with a very human subject matter. And with time, having seen dozens and dozens of photographers venture out to make work and to then produce these kinds of books that lack a human presence (bar maybe someone’s hand in some ironic still life) I have simply become hangry: I’m (metaphorically) hungry for the depiction of human faces when human subject matters are being photographed, and I’m, well, exasperated by the fact that so many artists think that’s not necessary. It’s just baffling!

There were two reasons why I didn’t provide details of which book I received above. To begin with, I’m usually hesitant to be too critical of up-and-coming photographers, especially when it’s their first book (if the book ends up on some well known list the gloves will come off, though). And second, singling out one photographer would have been unfair — there are all the peers who’re guilty of the very same sin.

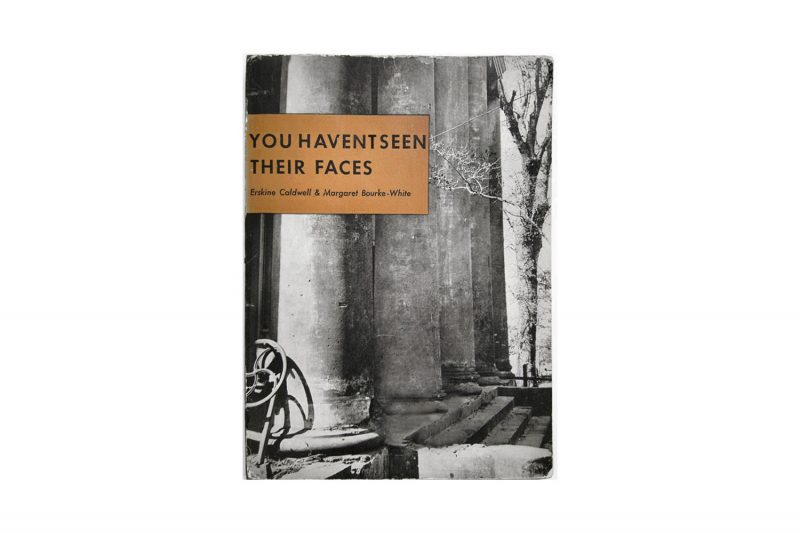

Those in the know will recognize the title of a 1937 photobook by Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White in this article’s header: You Have Seen Their Faces. I just snuck in a “not” for contemporary photography; I did the same in my admittedly somewhat sloppy Photoshop job — the picture above does not show the actual cover of the book. If you were to remove all the photographs of people from the book — or maybe all the pictures showing a face — you’d be left with precious little, a picture of a dilapidated shack here, some grimy soil there.

Right at the beginning, there’s a very interesting disclaimer that (in part) reads “No person, place, or episode in this book is fictitious, but names and places have been changed to avoid unnecessary individualization […] The legends under the pictures are intended to express the authors’ own conceptions of the sentiments of the individuals portrayed; they do not pretend to reproduce the actual sentiments of these persons.” In a nutshell, this is how larger parts of contemporary photography operate.

Someone might be photographed not to stand for him or herself as this or that specific person, but rather to be one of the many individuals that find themselves in some specific situation. This approach isn’t acceptable in documentary photography any longer, but for sure it’s very common in the larger world of art photography. And it’s a very good approach because if we, as human beings, connect with anything, it’s first and foremost the human face.

All of this makes the absence of human faces in so many contemporary photobooks all the more puzzling. Having taught photography for about a decade, I’m familiar with the kinds of explanations that might be offered. But, no, frankly none of those are going to cut it. The reality is that the absence of human faces in all those stylish books only makes for a grating effect: it is as if that absence was designed to demonstrate how mute even the most stylish photographs can be when an artist is not willing or able to do the final step.

Honestly, just put your camera in front of some faces (having obtained consent first), deal with the discomfort that might entail, make some good pictures, and then let us, the audience, see these faces in your quest to dive into whatever very human topic it is that in your newsletter you will probably describe as being “explored”!

You don’t even need to have that many faces in your body of work. But having them makes all the difference. Take the case of one of the finest photobooks produced over the past decade, Gábor Arion Kudász‘ Human. The book could have easily become one of the many books that triggered this piece, but it didn’t.

Concerned with how the built environment reflects some very basic aspects of human anatomy, the artist included a few photographs of human beings. He presents not just their hands or limbs against the types of bricks they deal with, human figures are also shown for scale and, crucially, as the very human beings they are. The book thus easily isn’t some cerebral photographic exercise around the idea of human scales, it instead dives deeply into our shared desire for a home.

This is not to say that every photography project about human topics necessarily needs a human presence. As an artist, you might be able to convince yourself that yours doesn’t. But at some stage during the process you might want to confront yourself and question your thinking critically: do you really not need any pictures of human beings, or are you merely buying your own bullshit?

The thing is that the presence of human beings in your pictures that focus on a human topic might make all the difference. And btw, photographing people but not showing their faces — I have plenty of such books, too, where everybody is always conveniently turned away — just amplifies the problem.