In this series on the forms and functions of photobooks, I have so far discussed four types of binding: how they function, their advantages and disadvantages, and how they can be used to support the underlying photographic material’s intent or message. To conclude this series, I thought I would move away from binding and focus on an aspect of photobooks that of late appears to have commanded more attention than binding: the use of different types and/or sizes of paper.

Especially after the run-away success of Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood, which included facsimile-style reproductions of archival materials, photographers started to pay attention to the fact that the pages in a book needn’t necessarily all have the same size. Of course, Peckerwood wasn’t the first photobook to employ this trick. Especially in the Netherlands, photobook designers have been working with different papers and/or different sizes for quite some time.

Conceptually, the use of different paper stocks and/or of different page sizes can be a very simple way to organize information in a tactile and/or visual sense. If handling some pages feels different than other pages, an attentive reader will pick up on this: these pages here look and/or feel different than those, so there must be a difference in what they’re talking about. In other words, the book’s very materials can contribute to communicating its intent in a very specific manner, if, of course, this is done properly. This isn’t quite the same as what was done in Peckerwood, where the sizes supported the idea of the facsimile. Still, the choices made support the underlying message, and that’s what you want for a photobook.

If as a photobook maker you want to work with the idea of different papers stocks and especially different page sizes you need to be careful. Unless you produce your books by hand, in which case the added work doesn’t matter all that much, in the case of books being made by machines you need to consider costs. There might be added costs, especially if hand work is required.

That’s probably the very first thing you need to consider: given the choices made, can this book be mass produced easily, or will costs simply explode? Especially if you work with a publisher this topic is likely to arise. Experienced photobook designers know how their design choices relate to production, which, however, usually is not the case at all for inexperienced ones.

So the very first question you need to ask yourself is: is what I’m thinking I should have feasible? Can it be made, and can costs be kept under control? The second, equally important question is: does this actually make sense? What purpose do these different types of paper and/or page sizes serve?

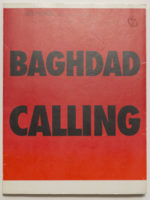

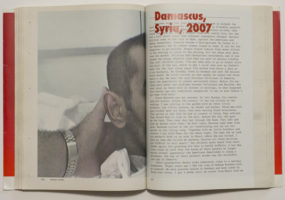

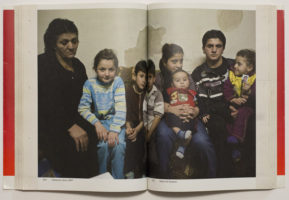

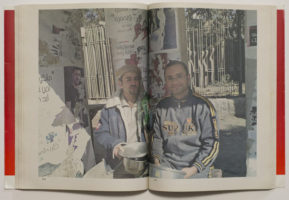

As in the previous articles, I’d like to look at a few example cases here. The first book is Geert van Kesteren’s Baghdad Calling. Published in 2008, the book broke new ground in terms of what a photojournalistic photobook could do. Van Kesteren visited Iraqi refugees living in Jordan, Syria, and Jordan and described their lives in exile. At the same time, he collected their cellphone photographs, which showed life in Iraq, a life that at that time was almost impossible to document for photojournalists, given how dangerous the situation there was. So there are two types of photographic materials in the book, Van Kesteren’s pictures and the citizen-journalist-style pictures by the refugees.

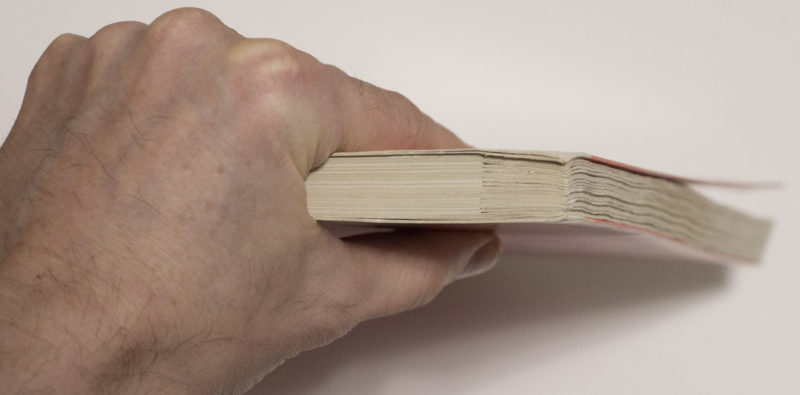

Given what I have been discussing above, it might seem obvious how to present the material, and this is indeed how it was done. Van Kesteren’s and the refugees’ photographs are printed on two different types of paper, namely for the former the kind of paper one would find in magazines such as, say, Time, and for the letter newsprint. In addition, the newsprint pages are 2cm (a bit over 3/4 of an inch) wider than the other ones. The design (treatment of the typeface) is uniform throughout the book. For most of the photographs, the difference between the photojournalist’s and the citizen journalists’ images is clear: the cellphone photographs clearly betray their origins through copious amounts of image artifacts, whether it’s blurriness, pixelation, or wonky colours. The paper choices reinforce the differences. At the same time, they also reference the typical life span of the pictures. Whereas Van Kesteren’s photographs might at best live for as long as a regular news magazine would be around, the refugees’ photographs are not unlike the ones we all take with our phones on a regular basis: to be looked at the same day and then mostly forgotten.

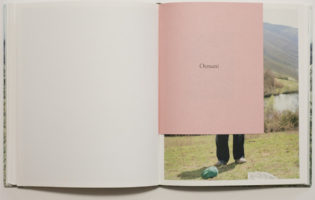

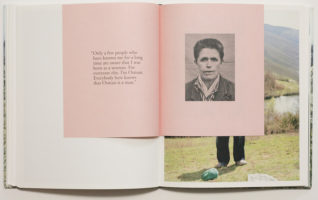

Even though it’s very different work, a similar device to organize photographs was used for Pepa Hristova’s Sworn Virgins. A book about a group of Northern Albanian women who out of tradition decided to live their lives as men, the photographer’s images here live side by side with archival photographs. While in the case of Baghdad Calling the vernacular material was given precedence over the professionals’, in this particular case, it is the other way around. The archival photographs, along with short texts, merely provide the basic context for Hristova’s pictures. Consequently, the archival materials and text are featured on small inserts, using a rose coloured thin paper stock that feels quite cheap compared with the paper Hristova’s photographs are printed on. Thus, in addition to the differences between the pictures, there also is a hierarchy being communicated: Hristova’s photographs are clearly the ones that carry the message.

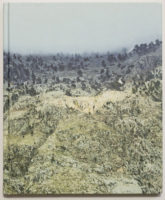

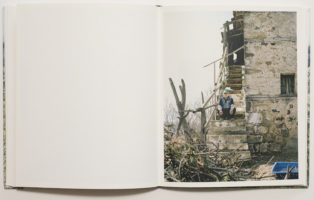

In terms of sizing, Max Eicke’s Dominas operates in just the inverse way than Sworn Virgins. While the paper stock the pictures are printed on feels like it’s of higher quality (it’s a slightly heavier white paper), the pages are actually smaller than the whole book. There are three different sections. As already noted, there are, first, the pages containing the photographs. There then are pages that contain text in the form of quotes from the women portrayed in the pictures. These pages have the same size as the picture ones, but it’s a different paper stock (see pictures). It’s red, and it feels like an office-paper stock. These two types of pages are then embedded in larger pages, which large rasterized segments of found pornographic images, printed in black and white.

The structure itself is simple. There’s no title page, so the first raster spread is identical with what ordinarily would be the end paper. There then is another raster-only spread. After that, there is a text page inserted. Into the next two raster-spreads, there are picture pages inserted (one each). Then one text page, followed by two picture pages, etc. until the end. Consequently, those who don’t read the text will experience a book focusing mostly on the photographs. Sworn Virgins doesn’t follow quite as strict a pattern, but the smaller pages there clearly separate the different chapters. In Dominas, there are no chapters.

As I hope to have made clear, apart from supporting facsimile reproductions of archival materials (Peckerwood style), different paper stocks and/or page sizes can be great tools to help organize content in a photobook. For this to make sense, there needs to be a variety of content being present. In the examples above, differences in the photographs arose through their sources. Obviously, there are other ways to separate out different types of images, but using paper stocks and/or page sizes provides a way that doesn’t require any further explanation: an attentive viewer will simply pick up on it. Other types of content that can be separated out are text and images, even though here, it’s not necessarily so clear per se why one would need to point out a difference. That said, though, printing text on the same relatively heavy paper stock as the photographs often feels a little bit over the top, so picking thinner paper is not a bad idea.

One needs to keep production issues and costs in mind. Wherever hand work becomes involved, production costs tend to explode. You probably want to stay away from that — even if you have the means to make such a book, the sale price would have to reflect the production costs, resulting in a pretty expensive book (unless you would want to absorb the added costs). A smart and experienced photobook designer will be able to come up with a design/production that will adhere to the budget. So as always, but especially when thinking about anything that involves a non-standard book format, with different paper types and/or sizes, speak with an expert to get help!

This article is the fifth in a series of five. You can find the other parts here: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5