A long time ago, I read an article online that argued that the Romans could have invented photography. Photography here has nothing to do with cameras; instead, it’s the type of photography that Anna Atkins engaged in before the invention of the daguerreotype. Obviously, the Romans did not have the required chemicals at their disposal. But they had something else that has existed all around us: plants. Using their leaves, you can produce chlorophyll prints.

Of course, a photographic concept is one thing. Marrying it to the photographs themselves — creating a meaningful connection between process and the larger idea — is quite another (this is where about 99% of all process-based photography falls short). In the case of chlorophyll prints, I find it difficult to imagine a better use than Binh Danh‘s in his Immortality: Remnants of the Vietnam and American War.

Danh arrived in the US as a refugee in the late 1970s. His family — mother, father, and three other siblings — had left their native Vietnam by boat. The exodus of Vietnamese people using rickety boats forms one of the first major news items that I remember vividly. I was just old enough to be able to take in the news on TV in a somewhat more conscious fashion. Growing up by the sea, I knew of its powers. How or why all those people would risk their lives that way my ten-year old mind was unable to comprehend. This might also have been the first time in my life that I became aware of what I would later understand as desperation.

Whatever his parents’ desperation might have been at the time, Danh was much too young to understand. Born in 1977, he arrived in the US when he was two years old. But growing up, there were early reminders of the fact that he was in fact somewhat different. In The Enigma of Belonging, he remembers fellow high-school students at school discussing a possible class trip to Mexico. “I chimed in that we just needed our green cards, and the other students burst out laughing.” (quoted from the conversation with Boreth Ly, p.157 of the white volume) Now, of course, there is the persistent anti-Asian sentiment in the country that periodically erupts into violence (more information here).

Under ordinary circumstances, you can’t bring much when you travel. When you flee your native country on a boat, you can bring even less. Maybe you’ll bring a few family photographs, such as the one of Danh shown in the book that looks like it was folded and stored near someone’s body. Photography is a way of connection with oneself and one’s biographical, cultural, and societal past — and present. If anything, that realization provides the red thread through The Enigma of Belonging.

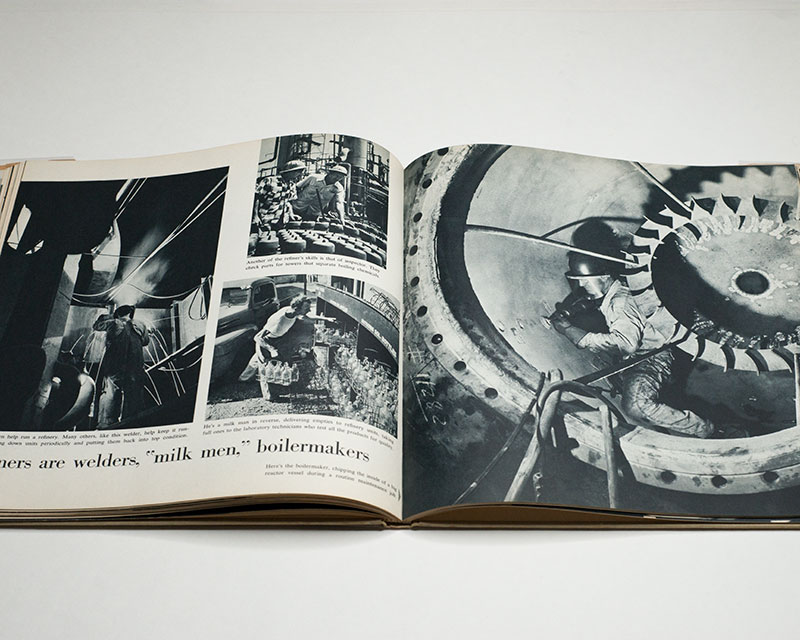

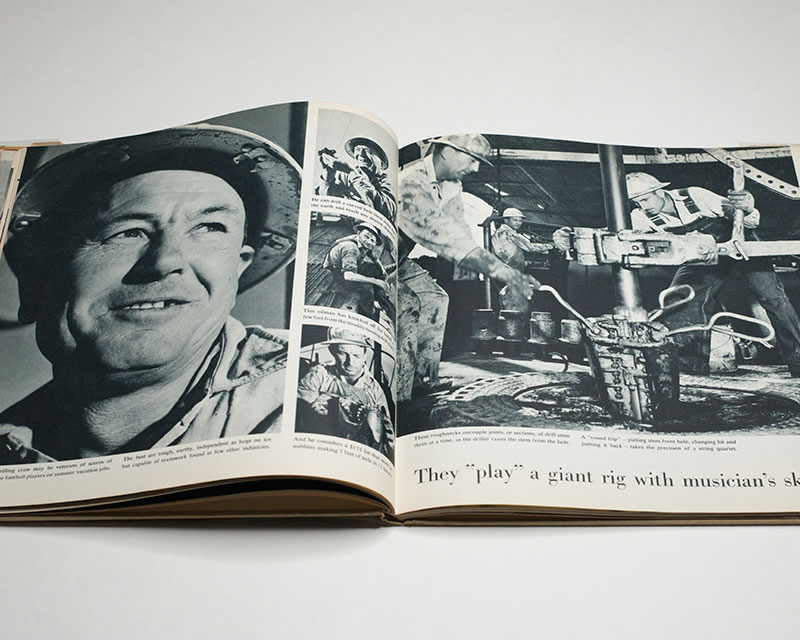

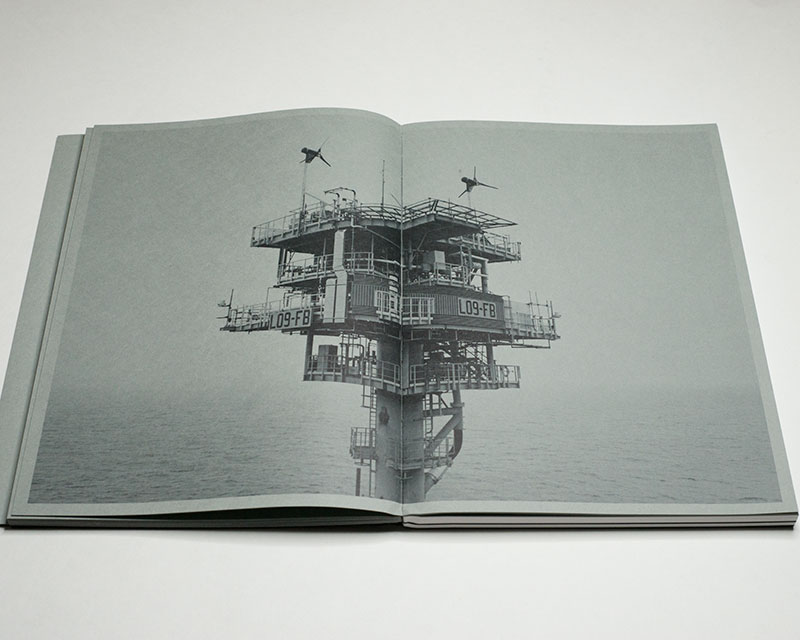

With Immortality: Remnants of the Vietnam and American War, Danh created a unique visual record of the war that would drive him from his first home. He “etched” (if we want to call it that) photographs and parts of news-magazine reports on leaves using the chlorophyll-print technique. The outcome is more haunting than beautiful. This is not to say that the images aren’t beautiful. But whatever beauty they might have pales in comparison to the overall effect. Ever since I first saw these photographs, I had hoped they would one day find themselves printed in a book.

During the war, the US defoliated large parts of Vietnam, leaving behind a vast and terrible legacy in the country. Creating the images on leaves thus produces an immediate connection to the war. Even if these aren’t the actual leaves scattered on Vietnamese ground, you could imagine that these ghost images would have appeared at the time.

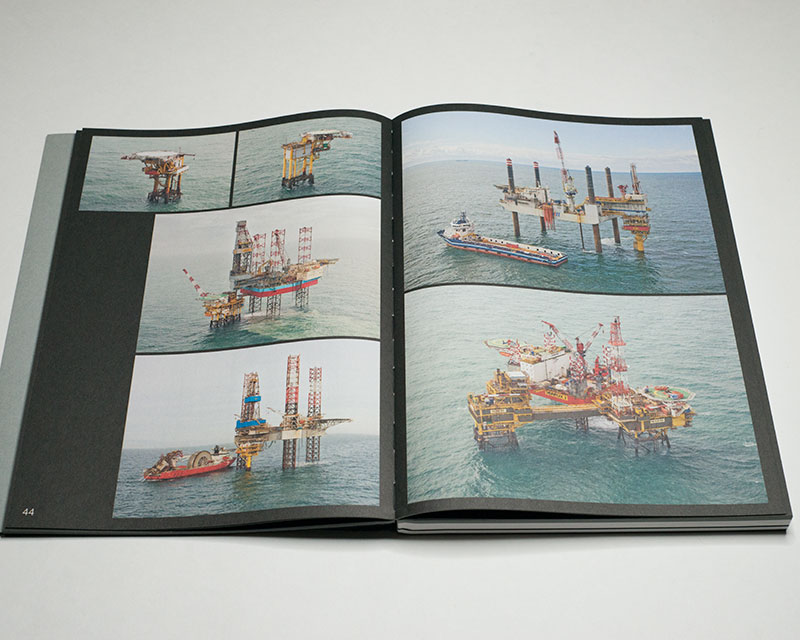

The Enigma of Belonging consists of two books in a slipcase (one has a black cover, the other one a white one). The black volume contains the images from Immortality along with another project that I will get to below. The white volume presents essays alongside what you could consider complementary material.

Most of that material centers on Danh’s family’s experience as “boat people” (that is in fact the actual term). There are family photographs and documents, there are photographs taken much later at the remnants of the refugee camp the family lived in for a while, and there are other photographs related to the Vietnam War that the artist collected. The combination of the essays and the supplementary material provides an indispensable background to Immortality and in particular to Danh’s life conundrum, which is also expressed through the publication’s title.

What does it mean to belong? Where or how does one belong? For many people, those questions are never an issue. But there are others for whom there are no simple answers — maybe even no complicated answers. Danh’s fellow students in high school had him realize that his situation was different than theirs. Back in Vietnam, though, he is — in his own words — a việt kiều, a Vietnamese foreigner.

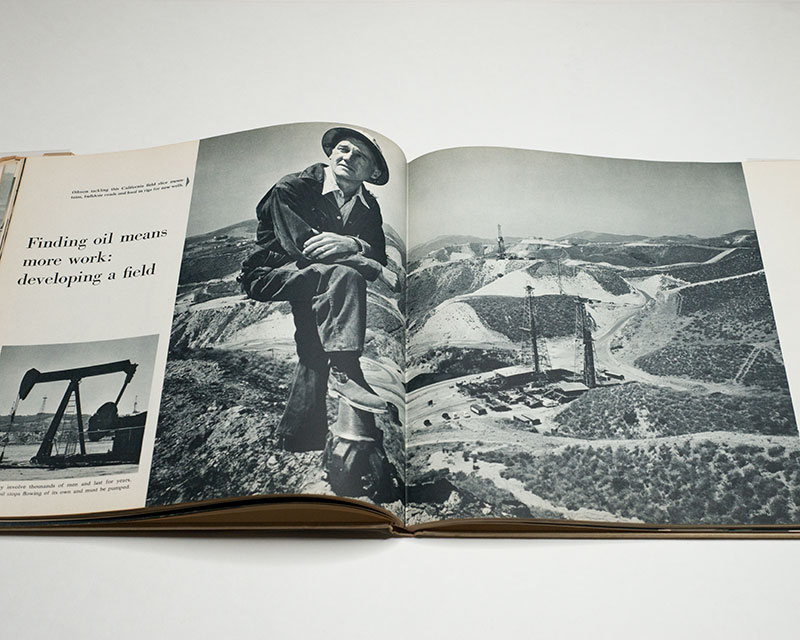

This is an experience shared by many other people, whether in the US or elsewhere. I don’t mean to lump all of their life experiences into one. My focus here is only on the aspect of belonging. The reality is that when you stop belonging somewhere — or when you never belonged in the first place, then it’s very hard, if not impossible to get it back. I see the second major body of work in The Enigma of Belonging — daguerreotypes of US national parks — as an expression of exactly this underlying concern.

After all, what could be more American than going to, say, Yosemite, an area that has been used to express Americanness through photography (if you’re interested in finding out more about this, read Tyler Green’s Carleton: Watkins Making the West American)? But how can you portray these places in such a fashion that people will not immediately think of Ansel Adams?

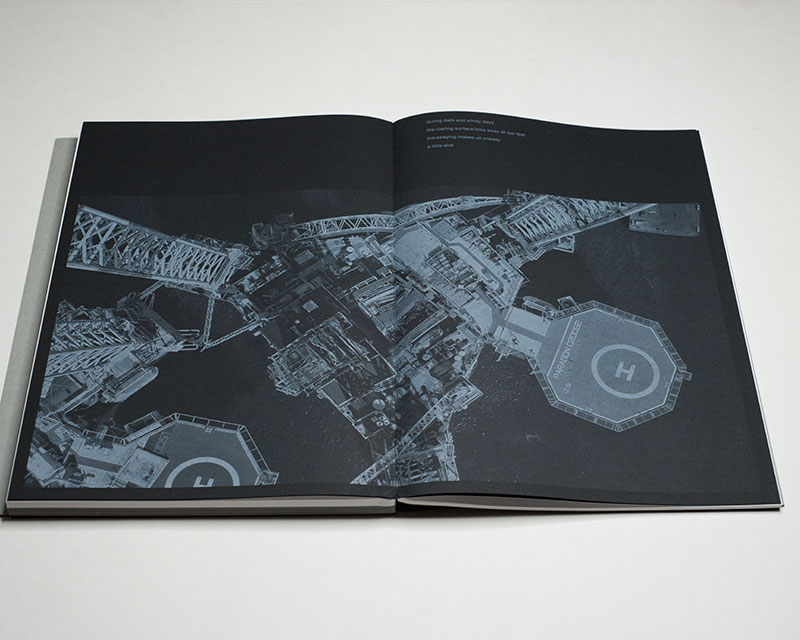

This is where the daguerreotypes come in. If you have ever seen a daguerreotype in real life, you know how difficult it actually is to see the image. It sits on a polished mirror, which you have to angle just right to be able to see. In The Enigma of Belonging, the images were printed with metallic inks that sit on coated paper. This brilliantly bring the viewer close to the experience of seeing the original daguerreotypes.

The end effect, of course, is that you never see just the image. You’ll also see a lot of what’s around you reflected in the images, and if you hold the book just right, you’ll see yourself. How do you belong into these scenes? There’s no answer. There’s only the experience of it.

The Enigma of Belonging pulls all the right stops to achieve maximum effect. The books are very well produced, using a variety of different papers that each help communicate the material they’re presenting. The end result is a publication that is incredibly beautiful but in which the beauty does not distract from the haunting aspects that lie underneath the photographs: a gruesome war, a family seeking refuge in the very country that played a major part in brutalizing their home, a young son growing up and trying to figure out his own place in all of this.

Especially in these times, where so many other people are forced to leave their homes to try to find a decent life somewhere else, this publication is a landmark achievement. It should remind those with comfortable lives how important it is to be open to other people’s suffering and to other people’s attempts to also have a safe and happy life.

Highly recommended.

The Enigma of Belonging; photographs by Binh Danh; essays/interview by/with Binh Danh, Boreth Ly, Joshua Chuang, Isabelle Thuy Pelaud, Andrew Lam; two volumes in a slipcase with combined 276 pages; Radius Books; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!