Sometimes, the same books get made in very different eras. Almost inevitably, the books will look and feel very different, even if at their heart, they get at the same thing. Such is the case for Thomas Hollyman‘s The Oilmen and Tanja Engelberts‘ Forgotten Seas. Both books tell their stories through a combination of photographs and texts. Both are very well made productions. To understand how these books deal with the same thing, though, you will have to ignore superficial differences.

The Oilmen was published in 1952 and is essentially a piece of corporate propaganda: “This book, telling the story of men and women at work in a great industry, was made possible by the corporation of the employees of Shell Oil Company.”

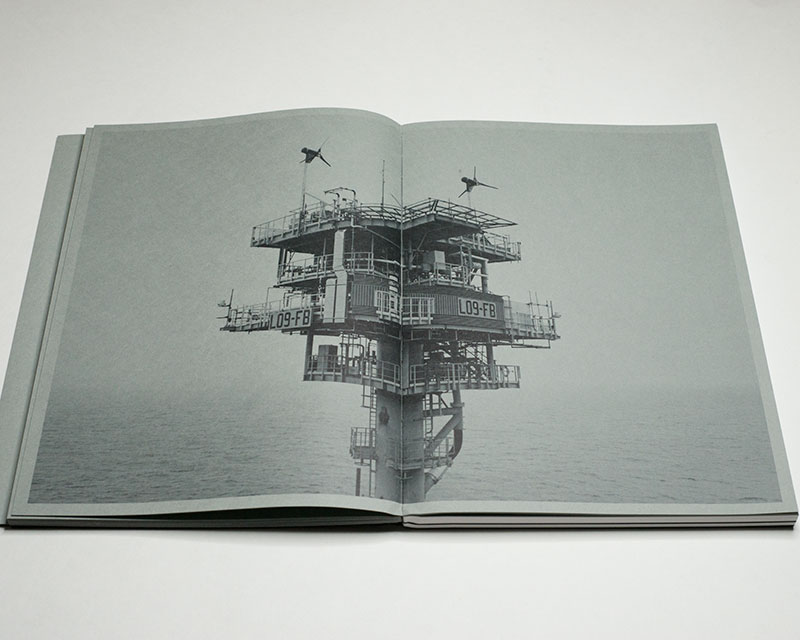

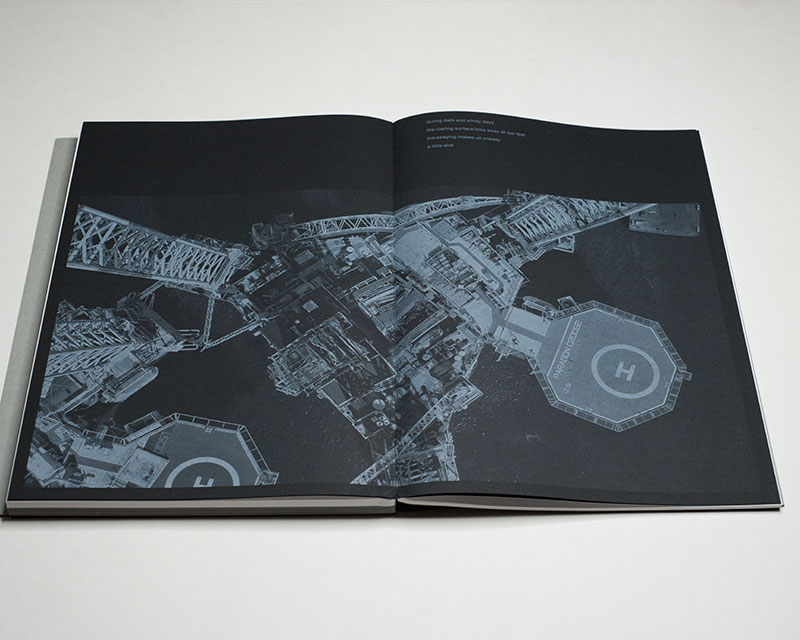

Forgotten Seas was published 71 years later. It is an art book that (in part) is being described as follows on the publisher’s website: “Forgotten Seas is a testament of seventy years of gas and oil drilling in the North Sea, an industrial landscape that is slowly disappearing.”

In these seven decades, a lot has happened with this particular industry. In a nutshell, we now live through the repercussions of its consequences by experiencing the climate catastrophe that has been long in the making. At the time of this writing, it does not appear as if we — and by that I mean the people who hold power, whether it’s derived from elections or money — are willing to do anything about that.

But a lot has also happened in the world of photography. Even as there still is the occasional lazy argument over whether the medium is art or not, for better or worse photography has entered art museums and is now being taught at art academies. The following might paint a picture with too broad a brush. But I think it’s fair to say that all in all, photography has mostly moved away from its subjects or subject matters, to instead approach them with a ten-foot pole.

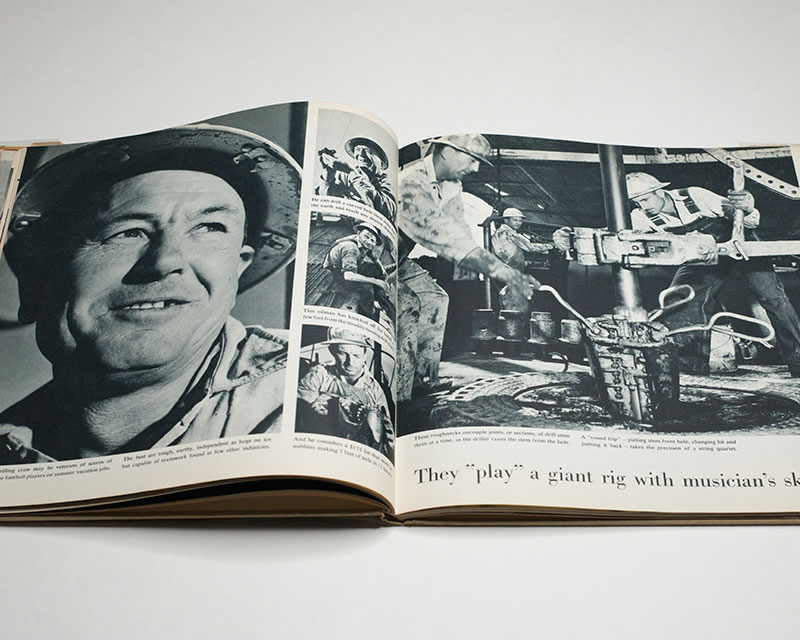

You can see these differences on the books’ covers already. The Oilmen features a smiling oil worker who is photographed as if he were holding a drill bit over his head. The photographer must have placed himself on the floor of an oil rig, pointing his camera towards the top of the drill tower (all of that using a flash). The book’s title sits between the oil worker’s head and the drill bit, printed in bright red. In contrast, the cover of Forgotten Seas shows a photograph of a sea-based oil rig that betrays signs of analogue or maybe digital artifacts. The book’s title sits at the very top of the page.

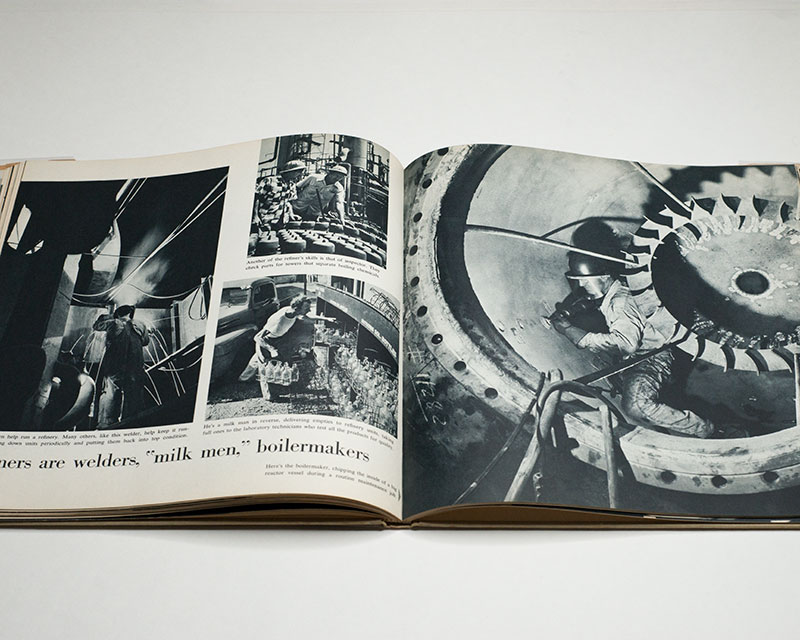

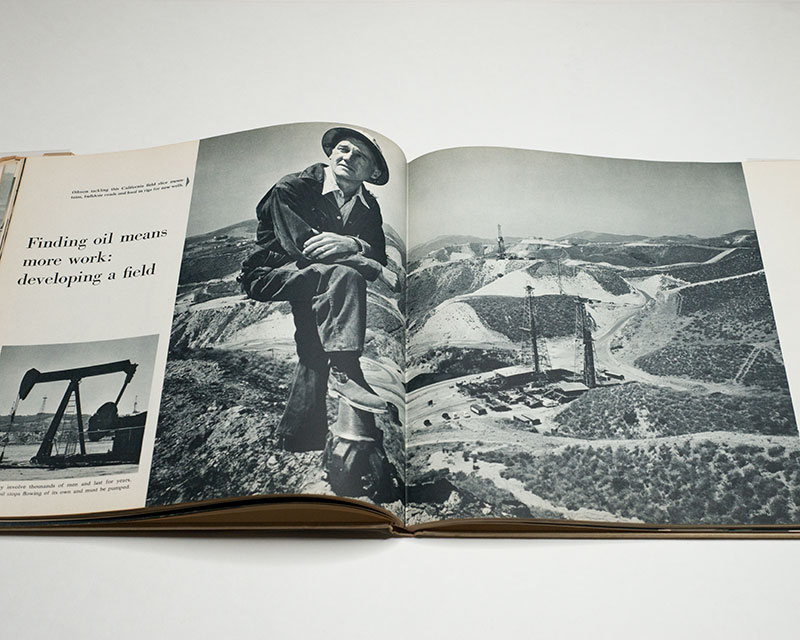

The Oilmen tells its story in what we now perceive as a very traditional reportage fashion. Differently sized pieces of text serve different purposes while sitting next to the photographs that are organized in any number of fashions across the various pages. There are captions, there are longer pieces of text, and there are what look like pull quotes, even if they are not that.

This combination is very dynamic — as are both the photographs and the various texts themselves. However you might feel about the oil business, Hollyman pulled all available photographic stops, often for incredible effect. And the text drives along, making one breathless proclamation after another. For example: “Once captured, oil never rests. These men measure it, clean it and pass it on”. Why, oil is being described as if it were a wild beast!

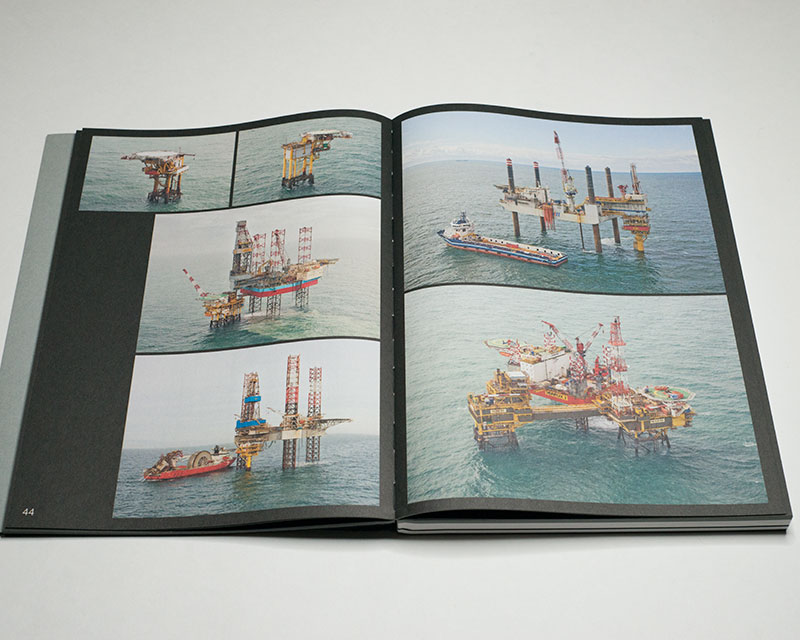

Much like The Oilmen, Forgotten Seas employs chapters. There are five: “Archive”, “Platform”, “Embarking”, “Horizon”, “Decommission”. Where The Oilmen focuses on the men and occasional women in the business, this book centers only on deep-sea rigs. Each of the chapters shows an aspect of their life time (as you can probably guess from the titles of the chapters).

In pretty much every fashion, the text is the complete opposite of the 1952 book. There are parts that read as follows. “twelve hour shifts / slumbering zombies // twelve hours on / twelve hours off” etc. In all fairness, some of the text is slightly livelier: “The Dutch, fresh-faced, a slight smile on their lips as if the joke is always on you. Then there are the silent Russians, the jokester Poles, the kind-hearted Norwegians.” But that’s about as exciting as it gets.

Photographs of human beings are mostly absent from the book. Instead, it’s many pictures of oil rigs; each chapter features assortments of groupings of such pictures in its spreads. There is ample repetition. However often I’ve looked at this book, the effect is quite numbing, with the turning of the pages turning into increasing tedium. Why, I wonder, am I supposed to care about any of this?

In fact, after I received Forgotten Seas in the mail I thought that there was no way that I would be able to write intelligently about it. I don’t want to claim that the book does not have a message or is not interesting. But I’m confident to write that whatever its audience might be, I am not a member of that group.

We’re now seeing an increasing number of exhibitions that focus on what appear to be very specific ideas of themes. They mostly feature photography that appears to have been made with the idea of looking as much like contemporary art as possible. And everything is tied together by some curator’s concept that is often explained in such a fashion that even after repeated reading I have absolutely no idea what they’re after. Again, I don’t think I am a member of the target audience of such exhibitions.

Truth be told, even as I am insanely critical of the way the fossil-fuel industry is actively destroying the very living conditions of this planet, The Oilmen has me a lot more engaged than Forgotten Seas. I know what the former is trying to get at, which offers me a lot of ways to respond to it, in part because the book is doing its job so well. I love the pictures and hate the message. In contrast, I have no idea what the latter is trying to get at. Oil rigs are constructed, they work, and they get disassembled? That can’t be it. But neither the pictures nor the text engage me enough that I feel compelled to dive in more.

I suppose what gets me these days is that so much of contemporary photography has such low blood pressure. At times, you don’t even know whether there’s a pulse! I want to look at photography that makes me feel something. It’s not that I mind the occasional cerebral exercise. But I find the steady stream of such exercises disheartening.

Mind you, what makes this realization even more bitter is that a lot of the photography that does not conform to this new trend merely copies old photographic strategies that are problematic for all kinds of other reasons.

I don’t know what the reasons are for what we’re observing these days. Is it all those art academies and MFA programs that are churning out “lens-based” artists? Is it the general dearth of a proper economic support system that has photographers reject more open messages, instead opting for the ten-foot pole approach?

In all likelihood, it’s just me. It’s my own fault. I want photography to be something that it mostly is not — or rather that photographers mostly decide to avoid, whatever their reasons might actually be.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!