Weddings happen in a larger context that is defined by social, religious, and political traditions and by capitalism. As such, they express social conventions and ideologies a lot more than people might want to admit. Whatever commitment to one another the two people getting married want to celebrate, there is the contractual aspect, which is highly regulated by both states and faiths.

I will admit that I have always been repulsed by some of the traditions around marriage, such as, for example, a father “giving away” a daughter — as if she were his property. But this is exactly part of that tradition, even if (one would hope) in modern times nobody thinks this way any longer. Property did and does play a huge role for a marriage. People might sign prenuptial agreements that secure the interests of both parties etc.

Wedding photography reflects part of that, even if the premise, of course, is that photographs taken at weddings celebrate the happy couple. Depending on the context (the society in question), wedding photography might produce different outcomes. But within a given context, the outcomes are typically so consistent that analyzing wedding photography to reveal what is being communicated is an extremely useful tool for visual-literacy classes.

Obviously, analyzing another societies’ wedding photographs often is a lot easier than one’s own. Learning to overcome one’s sense of familiarity, of ignoring what one simply takes for granted, in other words defamiliarizing the familiar (the essential Brechtian task) — that is the hardest part of becoming visually literate.

This work is not necessary for Sabelo Mlangeni‘s Isivumelwano, a collection of photographs taken at wedding in the artist’s native South Africa over the course of the past two decades. Already the very first photograph leads the viewer into uncharted territory. The upper two thirds of the picture look as if they had been covered with a veil. Only the lower third contains some information in the form of a voluminous dress touching the ground, with a pair of thin legs that end in what look like sneakers next to it (possibly a child’s legs).

The next photograph shows a column of cars that have balloons attached to them. Afterwards, we see two men holding hands, their fingers interlocked as if they were dancing. The man at the right is wearing an elegant bright suit. Of the other man we can only see a white glove on his hand and an outline of the left side of his face. His figure disappears in a dark shadow that cuts through the frame.

The fourth picture finally puts full focus on the idea of wedding. A bride is seated next to what might be her groom. But again, only parts can be made out: her veil, a big bouquet of flowers, the top of a white dress, the collar of a white shirt. All other details and faces disappear in the shadows.

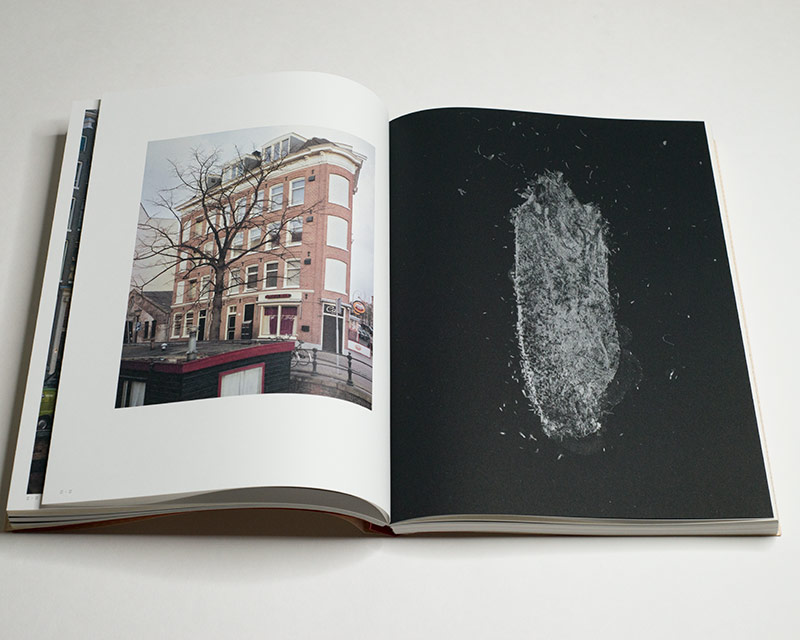

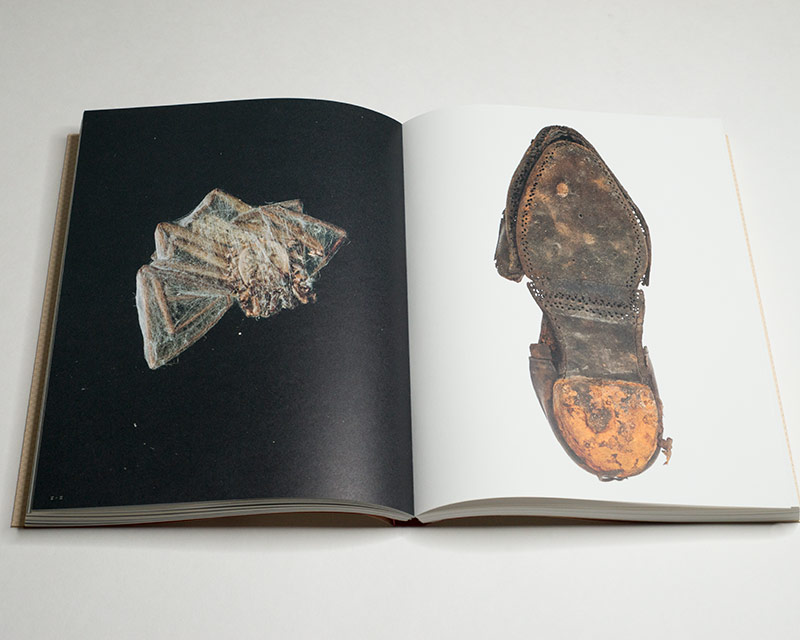

With few exceptions, it would be safe to assume that were members of one of the wedding parties to receive any of the photographs in the book, they would not be particularly happy with them. What one would expect to see in wedding photographs is largely absent. Instead, there often are photographs of meaningless details. And where a bride or groom can be seen, a photograph itself might show what I described above or might be literally degraded (underexposed or scratched). Often, the “right moment” has been missed.

What’s going on here?

“In Africa, like many other parts of the world,” writes Tshepiso Mazibuko at the end of the book, “young women are raised to believe that their ultimate duty in life is to become married and to become a loyal and devoted wife. […] Knowing the inner workings of such marital agreements and the idea of it being a kind of covenant, brought out my rebelliousness.” The photographs in the book speak of a similar sense of rebelliousness, of wanting to look past the carefully planned and staged beauty of the moment, to pull back the veil of what marriage might stand for.

As someone who has never been to South Africa and who has what realistically speaking is merely surface knowledge of the country’s most recent history, there are many aspects of the book that are likely to escape me. That its title, isivumelwano, is a word from Nguni languages meaning “a contract, agreement or alliance” I learned from a text by Emmanuel Balogun in the book. The deeper meanings of the word in its original language I can’t comprehend any more than, say, those of similar words in Japanese, a language I’m currently attempting to learn.

(As a very brief aside, I should have started learning Japanese a lot earlier: learning a language so different from my own and originating in completely different society involves a lot more than cramming vocabulary and understanding grammar. Instead, I have to learn details about social conventions and traditions in ways that also allow me to see how their equivalents play out in my own context.)

Given that in the larger context of the arts, photographs also have to conform to certain conventions, when first looking at the book I was briefly confused: even as I realized the source of my confusion, I also realized how conventions in different spheres can point at similar backgrounds, at similar expectations. Unlike wedding parties, though, I can work with the Brechtian idea of the alienation effect (or whatever your preferred translation of Verfremdungseffekt might be). So I found myself looking differently at the photographs, and more carefully.

The following might read entirely like too convenient a sentiment of writing, but I do think that I was able to connect some of the irritations I wrote about at the beginning of this piece with these pictures. The pictures are irritating, and they were made with that idea in mind. Granted, if the book contained traditionally beautiful wedding photographs, I would be irritated for a different reason. In that case, however, I would hardly revisit it.

I had not expected to ever see a photobook made around wedding photography by someone consciously producing such pictures as an act of resistance, an act of wanting us to look more closely at what is going on at weddings to reveal the traditions and ideologies in the background. I also had not been expected to become engrossed in such a book.

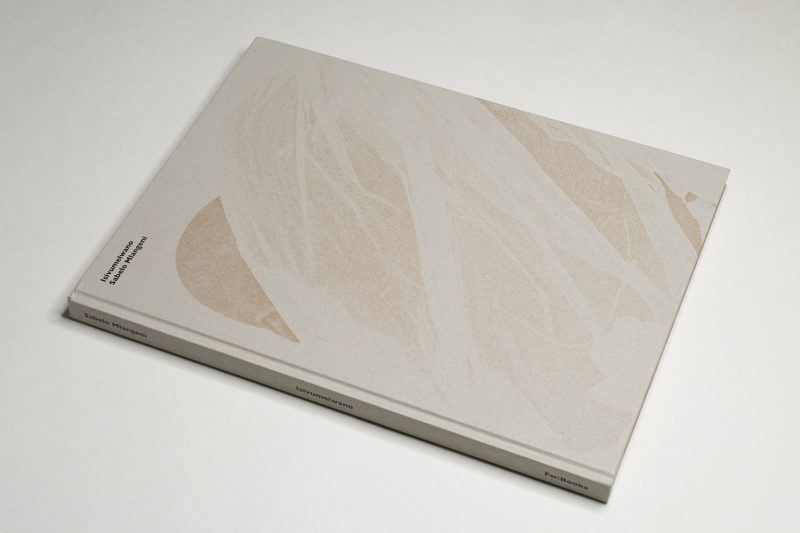

Isivumelwano; photographs by Sabelo Mlangeni; essays by Emmanuel Balogun, Athi Mongezeleli Joja, Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni, Tshepiso Mazibuko; 120 pages; FW:Books; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!