Every once in a while, photography produced outside the narrow confines of photoland manages to find its way inside, resulting in a breath of fresh air in an environment stultified by its own conventions and structures, in particular by its insistence on the model of the “master” photographer crafting precious images.

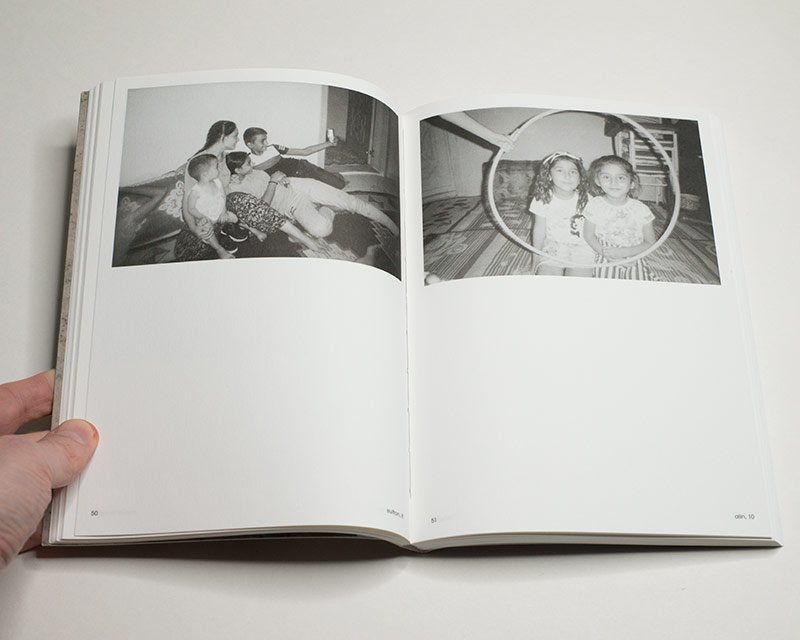

In many ways, the photographs in i saw the air fly do not conform to this “master” model. They were made by children and adolescents aged 7 to 18 who live in Southeastern Turkey, an area where people from nearby conflict zones have found a new home.

These are their names (and ages), in the order in which they appear in the book: Muhammed (17), Fehet (13), Ahmed (10), Refai (12), Alan (10), Ayshe (9), Omar (11), Renim (10), Bilal (13), Ilava (9), Dilava (13), Naime (11), Sultan (14), Alin (11), Melik (14), Nurma (13), Muhammed (13), Melik (13), Hala (13), Seyid (11), Ibrahim (14), Derya (15), Menal (13), Shakra (16), Resha (10), Reshit (10), Sultan (14), Ceylan (15), Hamrafin (13), Muhammed (10), Sultan (8), Alin (10), Refal (12), Sidra (15), Ilava (10), Eylem (13), Abdullsamet (13), Meryem (13), Zeynap (14), Roksan (9), Rojin (14), Menal (13), Halil (12), Selma (10), Rumeysa (11), Mahabad (18), Reshit (11), Hamoude (11), Halil (10), Baran (14), Abdo (10), Meltem (18), Rumeyse (11), Zeynep (13), Zeynao (13), Dialava (14), Selma (9), Esma (14), Emine (15), Ibrahim (13), Nalin (13), Nisrin (17), Kudbettin (14), Mehmet (14), Shehed (13), Alin (10), Nevaf (13), Dilava (13), Nurma (13), Beyan (14), Hamit (12), Gizem (12), Cane (8), Melek (11), Cemail (13), Lara (13), Ertugrul (12), Ibrahim (12), Haci (17), Alican (11), Menai (14), Yara (13), Sözdar (12). (There are no last names given.)

They were taught how to take, develop, and print photographs by Serbest Salih, a photographer and refugee from Syria who works at Sirkhane DARKROOM. Its idea is to give these children a creative, fun outlet. In 2019, Salih writes in the short afterword of the book, a mobile-darkroom component was added, which allowed access to smaller villages. With the onset of the pandemic the mobile darkroom also help alleviate reduced access to education. This two-minute documentary provides a good introduction to the darkroom.

In the book, we see some of the photographers’ faces as they took pictures of each other or of themselves. We have, of course, seen their faces before. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t their faces but faces of their peers as they appeared in reports of war or migration. Typically, those fleeing war or attempting to reach a safer home (possibly in nearby Europe) aren’t given a name, let alone a voice.

For example, as I’m writing this, a small group of migrants is trapped between Polish and Belarusian soldiers at the two countries’ border. Belarus has been using migrants to try to create a problem for its European neighbours, while Poland is in violation of its own laws and obligations by refusing to give them protection. So far, five migrants have died. News reports typically do not includes names of those who essentially have become hostages in an utterly shameful spectacle created by a dictatorship and an authoritarian regime.

But this is not the same thing as what’s in the book, you might note. And you’re right. At the same time, though, by pointing that out you’d engage in playing the game of relativism and denial that in the end is responsible for the miserable life so many refugees and migrants have to endure. After all, at the beginning of it all sit small considerations of difference that, with laws and rules added, are responsible for wealthy countries refusing to take care of those in need.

This is why i saw the air fly is such an important and overtly political book. It creates a powerful counter narrative to what dominates the news. It shows us the world that Muhammed, Fehet, Ahmed, and all the other children live in through their own eyes. That world is a lot less somber than you might imagine. Child play pervades the photographs — as it should. After all, childhood should be a time of enjoyment and fun, even if overall circumstances are less than ideal.

At the same time, there is a strong sense of self determination in the book, which comes across strongest in the children’s self portraits. Photolandians have become so used to maligning the selfie. I dare anyone to look at the selfies in this book and to dismiss them as superficial exercises in narcissism. Especially in this particular context, such a read would be almost obscene.

Instead, the selfies are an affirmation of the self that one might imagine cannot be had easily, given the circumstances: scarce resources and difficult access to education. But somehow, the children are unaware of all of this and simply take them, looking with big open eyes into their cameras.

In The Emperor’s New Clothes by Hans Christian Andersen it is a child that points out what is there to see for all: the emperor is wearing no clothes. In a related fashion, in i saw the air fly it’s children who show us how wrong and misguided our ideas of their lives are. They are human beings deserving of a life without hardship just like the comfortable rest of us.

When I looked through the book, I remembered what I had read about it in a number of reviews. In almost all of them I couldn’t help but feel that somehow, these young photographers didn’t conform to what was expected of them. It’s not just that migrants tend to remain nameless, we Westerners also seem to have very clear ideas of their intent and motivations — as communicated by our own media (with its helicoptering photojournalists).

How else can we understand the surprise caused by these photographs: our surprise?

All proceeds from this publication will go to the Her Yerde Sanat-Sirkhane non-profit, the publisher notes.

Highly recommended.

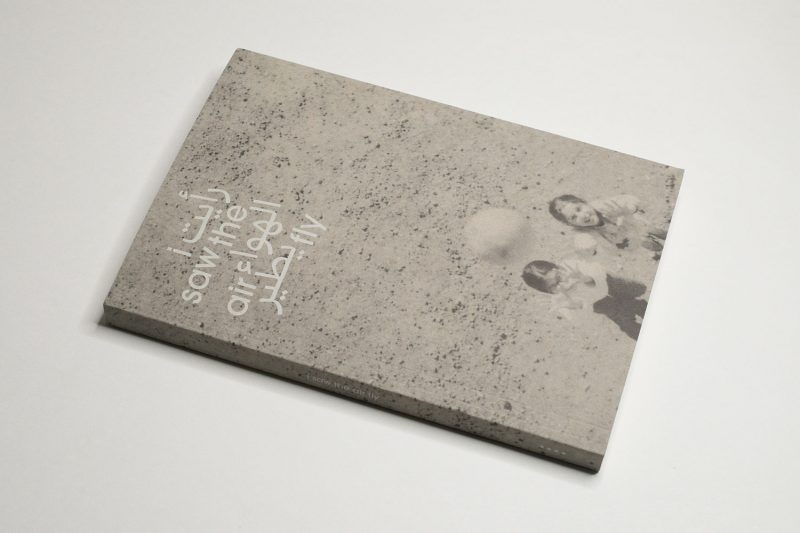

i saw the air fly; photographs by children living in Southeastern Turkey, edited by Liv Constable-Maxwell and Morgan Crowcroft-Brown; 160 pages; Mack; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.