“I wanted to show America what an empire in decline looks like.” writes Ken Light in the afterword of his new book Course of the Empire. Let’s unpack this.

To begin with, if you make a photobook you’re not going to reach America. You’re making a book for the tiny sliver of the population that looks at photobooks. Don’t get me wrong, I love photobooks. But not for a second do I believe that the people who look at photobooks (let alone buy them) are in any way representative of the countries or societies they live in.

Furthermore, a hefty coffee-table book is a luxury item. In fact, I’d be happy to argue that most photobooks are luxury items (mine included). Nobody needs a photobook in their life if their basic needs — shelter, general sustenance — aren’t met. In fact, I wager that the majority of people depicted in Course of the Empire wouldn’t be willing or able to buy the book that purports to focus on their lives.

Of course, in an ideal world, photobooks would occupy the same places that other cultural items exist in (novels, movies, etc.). But they don’t. Consequently, I need to focus on the world we have, not the one I want. I don’t necessarily want to get into a discussion of luxury items, given that a discussion might not be as clear cut as you might imagine. But in some ways I like that photobooks are luxury items, and here’s why.

In our world, for many people it’s an investment to buy a photobook. I don’t mean that in the neoliberal way (the way wealthy collectors think about it). Instead, I mean that with limited resources, someone will have to make a decision whether to buy this book or that book. The way I see it, from this fact arises a responsibility for photobook makers: you will have to make something that justifies someone’s investment, that gives the people who buy your book something to chew on.

I suppose you could say: “no, I don’t think people need something to chew on. I think it’s fine to entertain people.” Fair enough. I’ll admit that’s not my line of thinking. But I think it’s obvious from Course of the Empire that it’s not intended to entertain. It’s intended to shake people. I know this because I’ve read the afterword: “Surely we’ve hit bottom,” Light writes, “a nation drunk and stumbling.”

Does the book offer something to chew on, though? In some sense, it does, if you come from its maker’s place: “THIS IS NOT THE AMERICA I GREW UP IN.” — that’s the title of the afterword (including the all caps). And this brings me back to the quote I started this article with. “I wanted to show America what an empire in decline looks like.” If you start out with your conclusion, how will you be able to arrive at anything other than that, which you already know? What are you going to learn? What are you chewing on?

I’m writing this article on 11 September 2021, the 20th anniversary of the infamous terrorist attacks. You’ll have to believe me that that’s just a coincidence. In fact, had I paid more attention to the calendar instead of merely scheduling my articles by week, I would have done this differently.

I’m also writing this article as someone who was born in another country (I arrived here when I was in my early 30s). If there’s one thing that strikes me about the United States, something that I just don’t see in any other country I know, it is this: the country is completely enthralled with its own rhetoric, a rhetoric that’s hard to reconcile it with actual facts.

For example, NBC Nightly News end each day with a segment entitled Inspiring America. Whatever might happen on a given day, the last thing viewers see is some uplifting piece where you know that in thousands and thousands of households people are reaching for their tissues. Where in Germany the news might end with some report about a dog reunited with its owner, some little story that becomes meaningful because in the larger scheme of things it doesn’t mean anything, here, a little story is used as proof of the ultimate goodness of “the nation”. Everything in the news might have been terrible, but “the nation” still stands tall. That’s agitprop.

But the rhetoric sounds so good, doesn’t it? If you read the declaration of independence, for example, there is a lot of uplifting material in it. It’s written very well. It’s simple to see how one would cling to it as proof of the goodness of the country.

At the time the declaration was written, though, those words actually didn’t apply to many people. If “all men are created equal” how come some of them were slaves? Fast forward to today: former president George W. Bush (responsible for the wars that just ended) decried that “[w]hen it comes to the unity of America, those days seem distant from our own.” Need we dive into the reality of that unity, let alone into how Bush was responsible for undermining it a lot further?

Light’s sentiments are the opposite of Bush’s. His afterword also starts out with some ideal times (in this case, the short Kennedy era). From then on, the narrative goes, it all went downhill. But the general lament is the same. It’s the American lament, that, by the way, really only makes sense for white people. “In comparison with a future we don’t want to inhabit,” Maria Stepanova writes, “what has already happened feels domesticated — practically bearable.”

Here’s the thing: You never live in the country you grew up in. It just doesn’t happen. Heraclitus already noted that you can’t step into the same river twice. Things change, ideally (but not always) for the better. What is more, the actual reality of the beauty of past “unity” that Bush invoked (a sentiment that’s frequently mirrored by the current president) and of Light’s Kennedy era doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

In fact, it’s deeply reactionary to long for some supposedly better in the past (regardless of where you might fall on the political spectrum). If you look at the course of history, that approach has mostly been used by the wrong people, often with disastrous consequences.

What I’m after here is the following: if you set yourself up with a problem or challenge, and you pre-program the desired solution to it, then it’s very unlikely that you’re going to learn something, let alone achieve what you’re after. Instead, you’re guaranteed to chronicle your discontent.

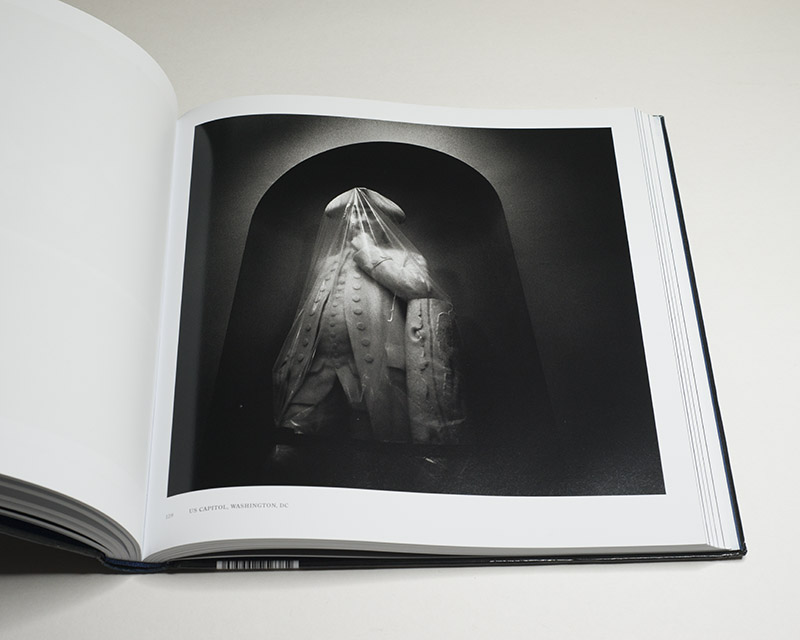

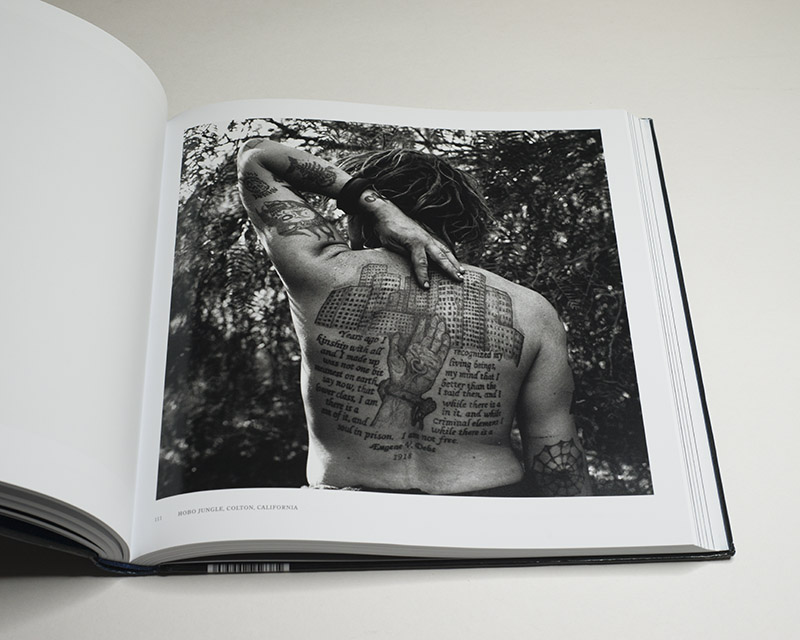

For his book, Light crisscrossed the US, to photograph homeless people in a lot of places, county fairs in the so-called heart land, fashion week and a private club in New York City, futures traders in Chicago, various demonstrations in a number of places, congressional hearings, the US-Mexico border, and much more.

I’m reminded of how US news organisations operate. For example, whenever they want to get some input from “real people”, they seek out some diner in the so-called heart land. Apparently, that’s where you can find “real people”. This approach has become so common that it has now resulted in a small industry of critical articles about it (if you’re curious, here’s one: Drive-by journalism in Trumplandia).

The problem with Course of the Empire isn’t that what it depicts isn’t real. The problem is that it remains self contained. In much the same fashion as the photographer didn’t challenge his own thinking while photographing, the resulting book doesn’t challenge the conversation. It’s a book for people who know they want their ideas confirmed, who want to look at art that tells them what they already know.

This is a reflection of a nation that believes in its own rhetoric instead of challenging itself to live up to it.

Photographers have been documenting, say, the homeless for a long time. For sure, homelessness is a pressing issue. And yet, nothing ever changes. You could retreat now and say “but photographs don’t have the capacity to change”. We’d probably agree on that. But it seems to me that the next immediate step would be to ask: why then continue photographing homeless people if the pictures don’t help them one bit? Maybe there are other ways to help (assuming there is a genuine interest in doing so)? Maybe photographic strategies need to change?

I wish I could stop believing in photography’s power. I wish that photography’s power extended beyond the private. In private settings, photography is enormously powerful — just look at how people use picture on social media to talk about their lives (whether or not those pictures are truthful is another matter and also besides the point). But the moment photographs arrive at the larger societal sphere, the power dissipates.

In part, Course of the Empire demonstrates the reason. That reason is not that dissimilar than, say, media outlets desperately trying to get their Saigon helicopter picture in Kabul. Instead of seeing the world for what it was, to make attempts to understand it later, they wanted to see it a certain way, to not even trying to understand anything later (and that’s exactly what has happened since, a few exceptions notwithstanding — make sure to read this article about Afghan women in the countryside).

Whatever you’re trying to look at with your camera, you want to be prepared for the possibility that the world offers something up to you that you couldn’t have foreseen — even (and especially) if what you encounter challenges you to the core. That, and I would argue: only that, is what defines an artist.

If you don’t do that, the risk is to produce something like Course of the Empire, a really well-made book that is sure to satisfy the people who believe in everything inside before they’ve had a look.

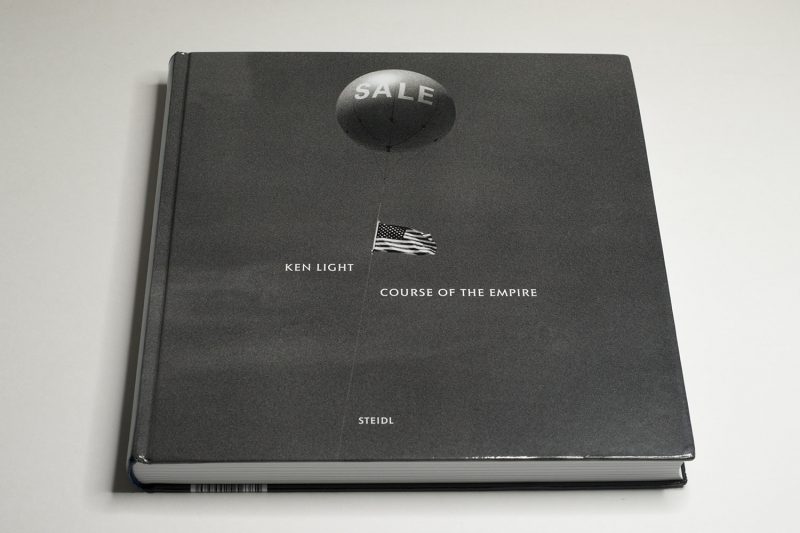

Course of the Empire; photographs and text by Ken Light; 276 pages; Steidl; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.