When I first heard of the exhibition Masculinities at London’s Barbican, I was intrigued and a bit irritated, the latter because of my own fraught relationship with the topic. I have never identified with many strands of the masculinity that would be associated with me, that, in fact, I was told was mine (I’m a heterosexual white man, now in his early 50s). I find its aggressive competitiveness unpleasant and unnecessary; I find its posturing of strength and dominance ludicrous and wasteful; I find most of its bonding rituals annoying and ridiculous.

Consequently, my adolescence was the probably worst time of my life, because I was expected to behave in ways that I simply didn’t identify with. I wasn’t a member of any sports club — not necessarily because I didn’t like sports (I eventually settled on playing squash and later did some karate), but because of the rituals associated with it, which were based on a male herd mentality that I didn’t want to partake it (to this day, I’m fiercely autonomous).

Having thought this over for a while now, I think this is the source of my irritation: given the society I grew up in and the society I now live in, masculinity for me amounts to an attempt to force me to be someone that I simply don’t want to be.

I’d like to think that my background has made me sensitive to all those struggling with being at the receiving end of the many consequences the dominance of masculinity has for our societies, but I can’t be sure. After all, if I were sure then possibly I would be too sure, falling into the very trap that I’ve been trying to avoid for such a long time.

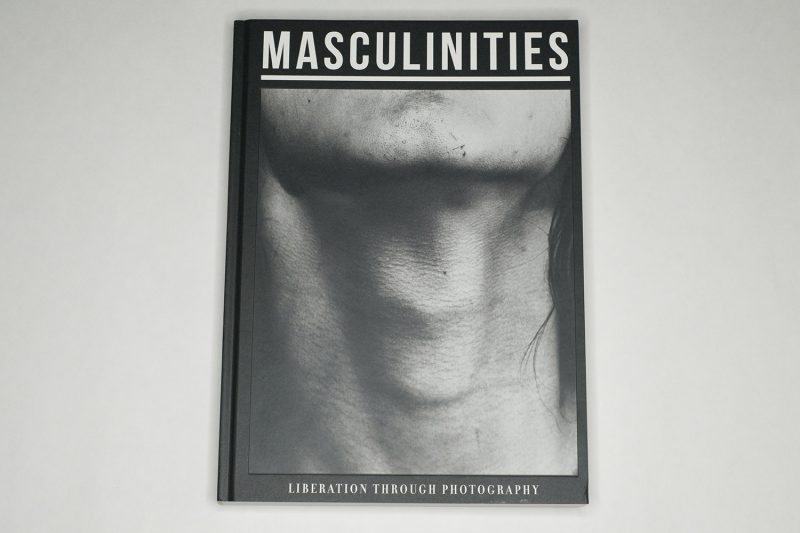

Earlier this month, I spent three days in London. I had planned to see the exhibition, only to find out it hadn’t been opened, yet. Fortunately, the catalogue arrived in the mail a few days ago, and I’m going to use it as the basis of this article. Truth be told, I’m not a big reader of wall text in exhibition spaces; but I did read the essays in the catalog. My reaction to the book thus might be different than to the exhibition itself.

“In the wake of #MeToo the image of masculinity has come into sharper focus,” the exhibition’s makers write, “with ideas of toxic and fragile masculinity permeating today’s society. […] Touching on themes including power, patriarchy, queer identity, female perceptions of men, hypermasculine stereotypes, tenderness and the family, the exhibition shows how central photography and film have been to the way masculinities are imagined and understood in contemporary culture.” (my emphasis — I’ll get to that part in a bit)

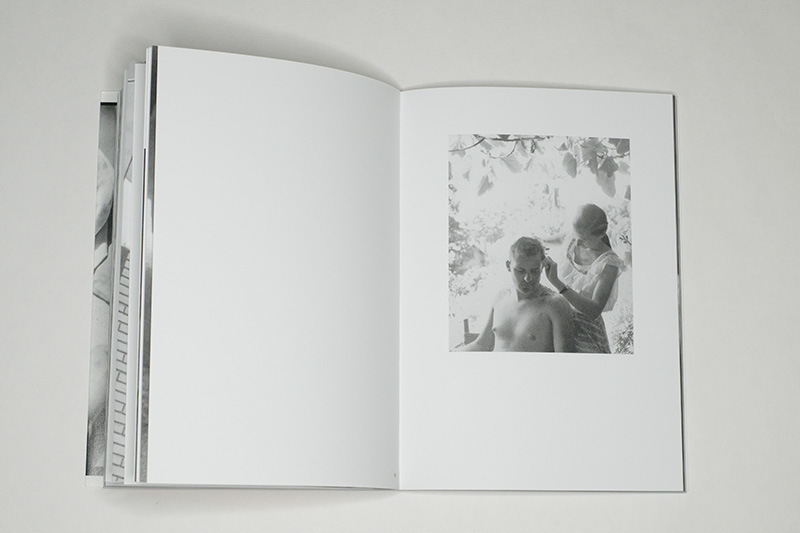

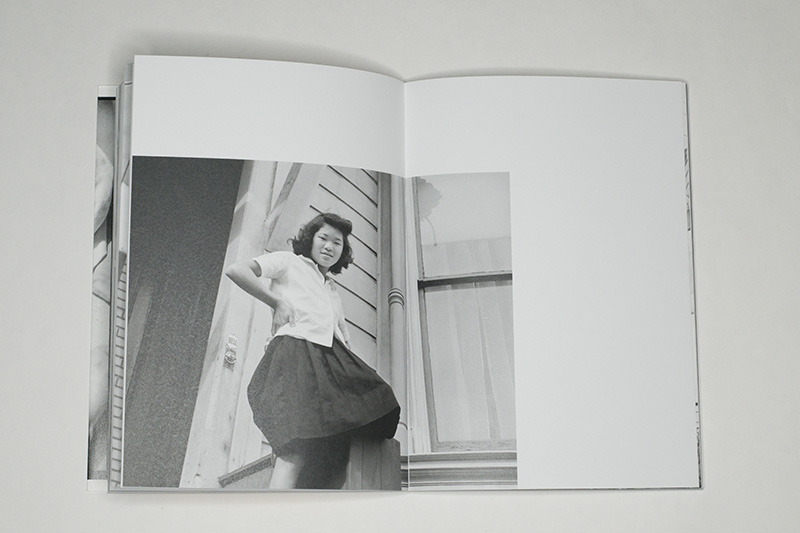

Masculinities approaches the topic through a series of sections that each explore a specific aspect. They are: Disrupting the Archetype; Male Order: Power, Patriarchy and Space; Queering Masculinity; Reclaiming the Black Body; Women on Men: Reversing the Male Gaze. Each of the topic presents an intriguing selection of work, with the usual suspects often being absent. I find this refreshing.

Obviously, I would be happy to argue over some of the curatorial choices, but that’s just par for the course. For example, instead of Richard Avedon’s portrayal of the United States’ 1976 power elite (The Family), I would have picked his portrait of the Chicago Seven against the leaders of the US military during the Vietnam War (I saw this pairing a few years ago in New York City; unfortunately, I was unable to find information about the show online).

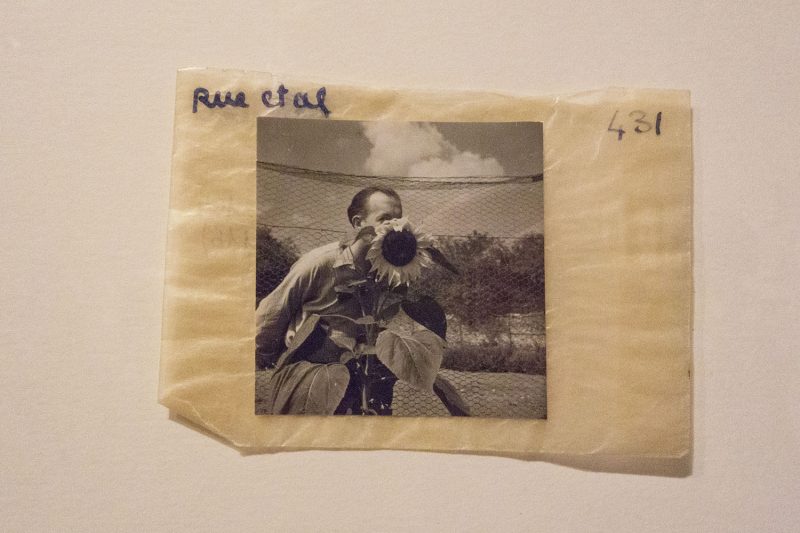

But there is so much very strong work included that, I suspect, might not be widely known even though it deserves to be. There is, for example, John Coplans‘ 1994 Self-portrait (Friese no. 2, four panels), one of the various pieces that I’m sure in its exhibition setting is even more impressive. There are George Dureau‘s 1978/79 portraits of B.J. Robinson (here’s one; two of the four reproduced prints were signed by both photographer and model). There are two panels by Marianne Wex for her 1977 Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchical Structures. The list goes on.

At times, I felt myself wanting to break up the rigid structure of the book/exhibition and create a dialogue between pieces that here are being kept separate. What happens if you show, let’s say, Samuel Fosso‘s self-portraits from the 1970s against some of Karlheinz Weinberger‘s photographs of queer rockers from the early 1960s? You would break away from the academic filing approach employed here (in this case Queering Masculinity and Reclaiming the Black Body, respectively), and that might be interesting. Again, much like in the case of my pick of different photos above, wanting something different obviously is easy for me.

My main criticism, however, is something else entirely. It’s the insistence on the sheer indexicality of the medium, the insistence that the only thing that is deserving of attention is the male body in the camera frame. In light of both the history and culture of photography, this omits one of the medium’s most problematic aspect, namely the machismo that has run through photography itself from the very beginning.

The topic that’s missing is the one containing the likes of Nobuyoshi Araki and Antoine d’Agata and Bruce Gilden and Garry Winogrand and Ron Galella and Terry Richardson and so many countless others. That would be the chapter of horror, and a large part of the actual horror would be to see how so many viewers wouldn’t even see the massive problem at hand: namely that the medium of photography, in the hands of mostly overly aggressive males, has become a handmaiden of exactly the toxic masculinity that this exhibition strives so hard to dispel. Photographs are being “shot”, there’s an insistence on that one successful photograph (besting all others), there’s the photographer as the hunter (Daido Moriyama even named a whole book The Hunter) on the prowl for pictures, etc. etc. etc.

In actuality the very making of the pictures and, consequently, the results have as much to do with masculinity — a mostly very narrow range of masculinity — as these various pictures of mostly male bodies. Where is the photograph of Araki posing next to a suspended bound female model? Where are the photographs of the mostly male photojournalists posing with a handful of cameras around their necks before the advent of digital photography? Where is, for example, Ron Galella’s What Makes Jackie Run? Central Park, New York City, October 4, 1971? Where’s the photograph of Lee Friedlander’s shadow on the back of a woman in the street somewhere?

What I’m after here is the following. It’s undoubtedly very interesting to look at how masculinity (or masculinities if you want to follow the exhibition’s approach) is portrayed in photography. But in light of the history of photography it’s equally — if not even more — interesting to look at how photography has been shaped through its mostly male- — I’d even argue: macho- — centric approach. So many photographs that do not explicitly show masculinity express masculinity implicitly. To understand the role of masculinity in photography means to study and understand this aspect as well.

So there is a lot left to be studied here that goes beyond what’s on display in Masculinities. The material at hand is very good and I presume it will challenge many ideas of how masculinity is presented in photographs. The next step now must be to look at how masculinity is presented through photographing — that crucial aspect of the male gaze that so often is ignored.

Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography; photographs by various artists; essays by Alona Pardo, Chris Haywood, Edwin Coomasaru, Tim Clark, Jonathan D. Katz, Ekow Eshun; 320 pages; Prestel; 2020