Up until very recently, there were two things I knew about Dora Maar, namely first, she was Picasso’s muse (ugh!), and second, there is a photograph of hers — entitled Père Ubu — that is a prominent example of surrealist photography. Here and there, I would see other photographs occasionally that had no visual connection to Père Ubu, making me curious about this particular artist.

•

The “muse” aspect has always given me the shivers. I personally don’t care what kind of relationship she might have had with Picasso. It’s the “muse” part that has always bothered me. It has bothered me here as much as anywhere else, given its inherent machismo, its reduction of a woman to a status that pretends it elevates her whereas in reality, it does the opposite. I find the word — and the idea as a whole — tainted through its associations with exactly the likes of Picasso.

•

Once I removed the “muse” part, I was left with that photograph of the baby armadillo. That’s not much. It’s not a photograph that lends itself to imagining something else (assuming one is familiar with surrealist photography). For that reason, I was looking forward to visit an exhibition at London’s Tate Modern, the opportunity of which presented itself given a very short trip to the UK.

•

•

As I made my way to the museum, I realized that its environs have changed quite a bit since the last time I went (roughly 15 years ago), and not necessarily for the better. Exiting the Southwark subway (“tube”) station, my walk forced me walk past quite a few rather gaudy looking buildings, the tackiest one a glass-clad tower near the river which appeared to house luxury apartments (the rich really have no taste). That put me in a bad mood.

•

But a bad mood is not a bad state to be in when going to a major art museum: it sharpens the senses, and it revs up one’s bullshit meter (assuming one has one).

•

What a delight to then come across Kara Walker’s Fons Americanicus in the building’s main hall! Other critics have written about it (example), so there’s no need to do so here. I lingered around it for quite some time, soaking in the fact that contemporary art can be very bitingly political without being clumsy, superficial, or merely didactic (which unfortunately it so often is).

•

Before seeing the Dora Maar exhibition, I briefly walked through one of the free ones. Setting out to write this piece, I only vaguely remember its premise, so I looked it up: Artist and Society (“artworks from Tate’s collection that respond to their social and political context”). That premise is sufficiently vague for it to contain a variety of material; but all in all, it felt too broad, too dispersed. Obviously, there’s nothing wrong with presenting a bunch of artists, each in their own gallery space, and an attentive viewer can make connections; it might just be that I’ve grown tired of this model.

•

Up one level, there was the Dora Maar exhibition, organized by Tate Modern, Centre Pompidou (Paris), and the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles), with curators from each institution involved. The first thing I noticed was the rather subdued light, which made for a somewhat cavernous atmosphere. Given there were many vintage and thus possibly light-sensitive materials on display, the lack of light made perfect sense, and it really forced a closer engagement with the many objects on display. That said, there was a sense of gloom hovering over larger parts of the exhibition that took away from the lightness and liveliness of many of the photographs.

•

As most single-artist exhibitions go, the organization was temporal as much as topical, leading the visitor from an introduction to various aspects of Maar’s work. The picture presented was one of an incredibly gifted artist who had engaged in a large variety of work, with Père Ubu being an outlier even within the surrealist section (they had painted this sub-gallery a different colour, not sure why). In a nutshell, Maar worked on all kinds of assignments and types of photography, with a general sense of the wittily absurd often lurking around the corner. I suppose this would in part explain this artist’s engagement with the surrealist movement.

•

•

I couldn’t say which parts of her work I most connected with. Most of what was on view showed an artist adept at making strong work regardless of where it would have to be filed. The street photography was just as good as the surrealist collages which were just as good as the social documentary work etc. Many (most?) of her male contemporaries excelled in one, but not in so many different approaches to photography.

•

The limitations placed on Maar because of the fact that she was a woman seemed pretty obvious to me. There were prints signed “Kéfer-Dora Maar”, which, the wall text (reproduced in a little booklet I took) explained, for the most part were Maar’s products — there was a shared-studio set up with Pierre Kéfer.

•

Another little nugget I picked up on (which, alas, I didn’t have the foresight to photograph so the details unfortunately escape me) was a caption underneath a portrait that Maar had taken of a female painter. The painter, I was told, had been put off by surrealist poet André Breton’s homophobia and sexism.

•

And then Maar ran into Picasso, who apparently encouraged Maar to return to painting. In a variety of ways, artists such as Picasso are like black holes, from whose pull nobody can escape. This was as much true for Maar as it was for the curators, because there was a whole room dedicated to the man and his work, with Maar having become a minor object orbiting the black hole. She had, one was told, documented Picasso’s making of Guernica, and she had been made the subject of The Weeping Woman.

•

As a visitor, I found this part of the exhibition jarring, but not in a good way. I had not come to see Picasso. And given that the two galleries after were rather weak, I ended up feeling that maybe one would take away less from this exhibition that one might have, had there not been such a focus on Picasso, the grandmacho of modern art.

•

•

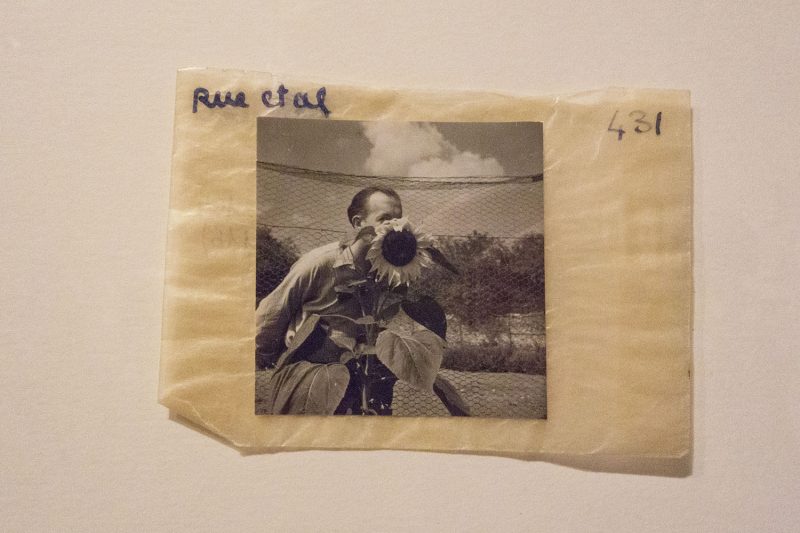

Tellingly, in that space, there was a small negative of Maar’s, a portrait she had taken of Picasso, which she had partly scratched. (There were a few backlit negatives on display through the exhibition.) Make of that what you will — I certainly did.

•

Who am I to tell anyone what to do, but I think the exhibition should have been a lot more feminist than it was. After all, what it did make abundantly clear is that Dora Maar is a very underappreciated artist, whose contributions to photography should be a lot more widely known — beyond Père Ubu. For example, her surrealist work included some very strong collage examples. Her street photography included plenty of what possibly would be considered classics — had they been taken by any one of the famous male photographers from the era.

•

I suppose it’s easy for me to demand not to put so much emphasis on Picasso — after all, most people will show up for exhibitions not because of what or whom they don’t know but what or whom they know. Still, it left me feeling disheartened to see that even in her own retrospective exhibition, Dora Maar ultimately was yet again reduced to being Picasso’s “muse” — despite the fact that it had been made clear what an incredibly gifted and accomplished artist in her own right she had been.