The simplest way I could describe Michael Ashkin‘s Were It Not For is to compare it to the music by British post-punk group The Fall, in particular the one produced from roughly 1979 until early 1983. Mostly devoid of actual melodies, the songs all begin and end, without much happening in between: a short phrase or even just a single note is repeated seemingly endlessly, with a cantankerous man (who might or might not have suffered from some form of mental disorder) spewing out cryptic words — an assorted variety of non sequiturs — on top of it all. Most music, of course, lives from repetition, but The Fall would drive the concept to its logical conclusion. Consequently, one of their earliest songs is entitled Repetition.

Their longest songs from that period, whether Winter or Tempo House or The NWRA or Hip Priest, drove home the actual point strongest, and they are the ones I revisit first whenever I decide to give the group another listen (if you want to try only one of them make it The NWRA). Much like in all good art, there is a world created, a world that is shockingly bleak and grim, a brutal world. If you’re in search of consolation, The Fall is probably not your cup of tea.

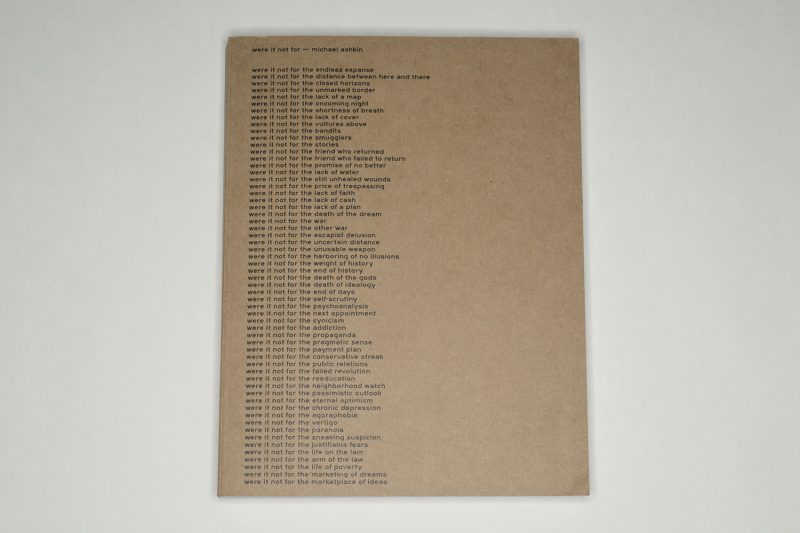

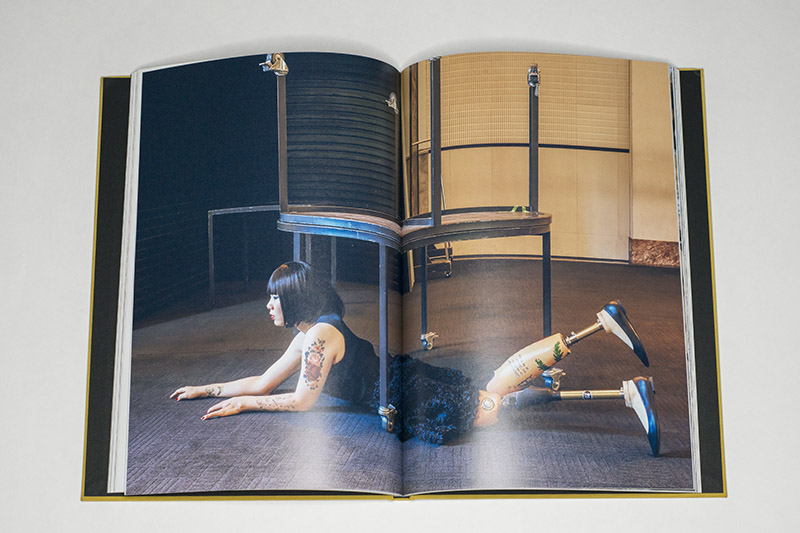

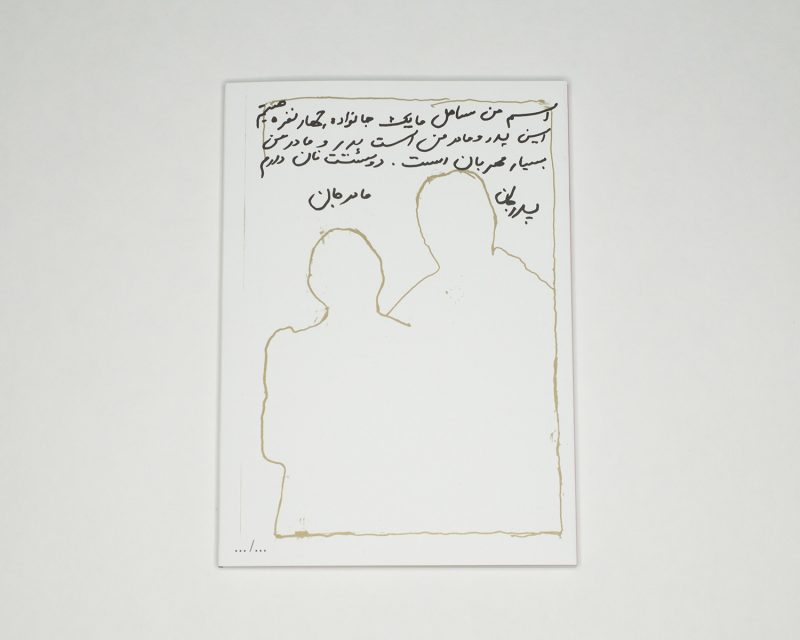

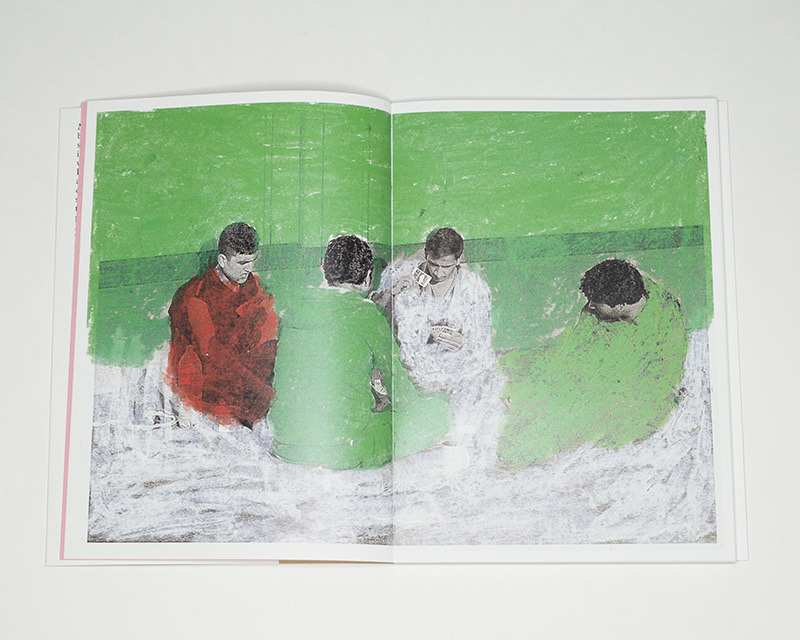

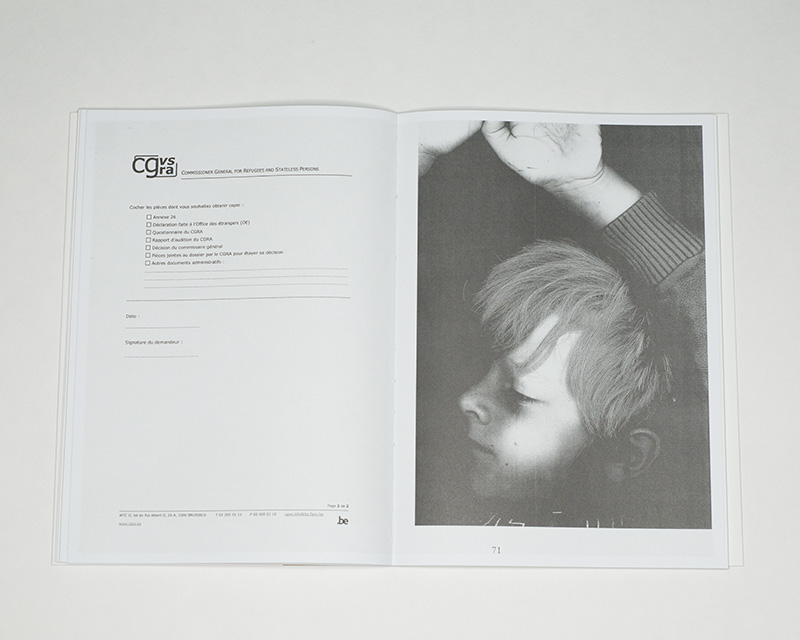

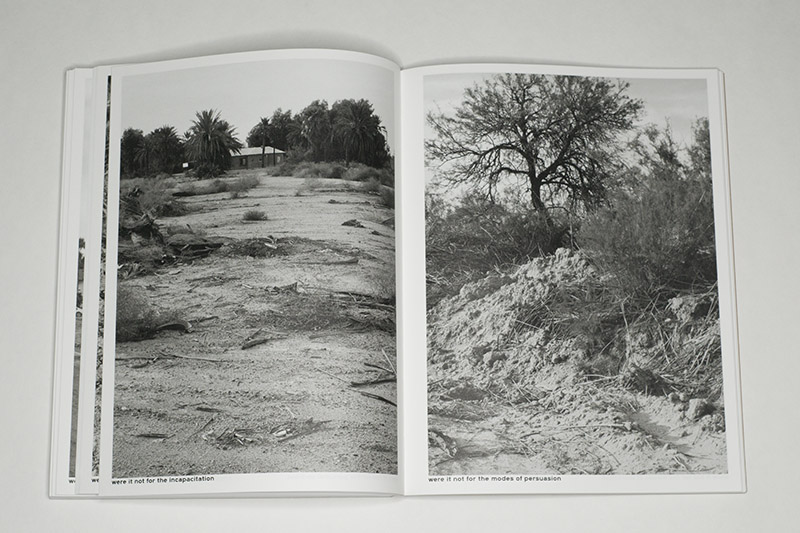

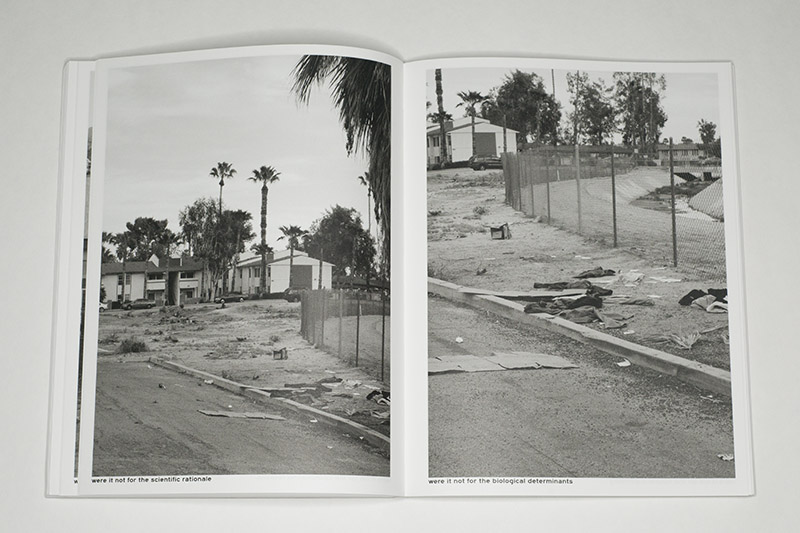

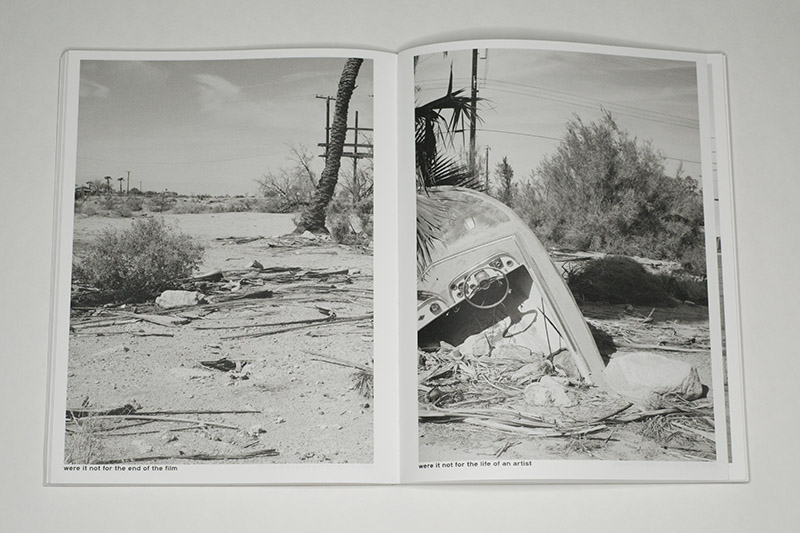

Were It Not For lives in this kind of territory. The book is easy to describe: a large number of photographs are paired up with phrases that all begin with the words (you guessed it) “were it not for.” Occasionally, such a phrase might be displayed on its own; in addition, there are longer lists of phrases on the book’s cover and before and after the section that contains the image. The photographs are all black and white, and they look like they were taken somewhere in California in an area that is bleak and grim.

Much like in the case of The Fall, to fully appreciate the book you will have to cast aside your expectations of what a photobook will do. This might be my personal read, but the idea of the memorable photograph is completely irrelevant here. None of the photographs are memorable, and many don’t offer much, if anything, to study. Just to be clear, I don’t intend this to read as a form of negative criticism — quite the opposite actually. Looking through the book, I found myself preferring some photographs over others, only to realize that that approach was completely besides the point: much like one doesn’t listen to The Fall for lovely melodies (there aren’t any), you don’t want to look at this book expecting precious pictures (ditto).

(Obviously, your mileage might vary, and you might consider these pictures as precious. OK, well, this won’t change any of the conclusions I’ll be coming to.)

Much as I could dive into the history of photography and dig out some references (for the photographs), I don’t think this would be very enlightening. In the end, the book is the book, and if anything one would need to refer to other books that achieve a similar effect. I can’t think of any. Leafing through the book, the viewer/reader is faced with a large number of photographs and short phrases that are all very similar and that build up to a portrayal of a place that has reached its nadir, without there being any way out in sight.

Wherever you look, whatever you hear, it’s all the same hopeless mess: a lived environment that more often than not looks like a garbage dump, with soulless anonymous architecture everywhere, and a cultural/societal environment filled with endless violence, dread, and despair.

Of course, that place is the United States of America.

Were it not for the nightmares.

I have been wondering when there would be a photobook about the Age of Trump. Here it is. As grim as it is, it is nothing but brilliant.

Along with Alan Huck’s I Walk Toward the Sun Which Is Always Going Down, Were It Not For provides a model forward for what can be done in/with photobooks. In both cases, text plays a very strong role; but it does it in a way that short circuits the kinds of anxieties that has most photographers stay clear of using words. In both cases, the text does not compete with the pictures (and it also is not used in a supporting role).

My hope is that more photographers will realize what can in fact be done with text. At the same time, these two books demonstrate that the form of the photobook is not exhausted at all. There still is ample room for a step in a direction not explored, yet. As someone who has been looking at photobooks for quite a while now, it is enormously heartening to see such experimentation and to see it done so successfully.

Highly recommended.

Were It Not For; photographs and text by Michael Ashkin; 256 pages; FW:Books; 2019

my rating system doesn’t take text into account (yet) so: not rated