In the world of photography, those portrayed are almost never given much (if any) agency, regardless however much is at stake for them. This basic fact constitutes a well-known problem that usually is ignored. Why, after all, should those in front of the camera be given a voice if the general idea of the photographer as genius artist/maker (or truth teller) is so predominant?

Photographers know what to do with their cameras, and they — plus their assorted hangers-on (editors, curators, critics, …) — define what a good picture is. That works for a large variety of contexts, but as has become obvious for many people — more often than not originating from groups that previously were at the receiving end of what can be done with a camera — it’s lacking in so many ways.

If we consider the ongoing migrant crisis playing out in large parts of the world, the aforementioned situation is directly comparable to how migrant issues are being discussed in countries that attract them: discussions focus on migrants, while mostly not giving them a voice at all — as if they had nothing to say whatsoever.

Somewhat related, this week I read a longer essay in a respected German liberal weekly in which an author professed her problems with what she described as political correctness. Again, those at the receiving end of derogatory language (minorities, migrants, etc.) were almost completely absent from the essay. The wronged ones, it was argued, were those using said language (whether out of ignorance or indifference) who’d then be sanctioned. That’s a crazy approach to the whole topic, and seeing it prominently featured in a liberal weekly made it all the more depressing.

In all of these cases, the absence of those that are being talked about — those for whom is most at stake — can only have a chilling effect on the resulting impoverished debate, for the most part enabling and benefiting those arguing for repression or rather: more repression, given how repressive migrants’ incredibly wealthy target countries already are when it comes to accepting those most in need of help and support.

Breaking away from the one-way-model of photography inevitably will mean breaking away from established modes of thinking about and evaluating images. As photoland’s ongoing agonizing engagement with pictures on social media demonstrates, old habits die hard. It’s a lot easier to decry the (supposed) lack of visual sophistication of those millions of people uploading their selfies, cat photographs, etc. than to try to understand the meaning and actual merit of those images in the first place. In a nutshell, what a good picture looks like is very different outside of the incredibly narrow confines of photoland than inside, as is the question how or why this matters.

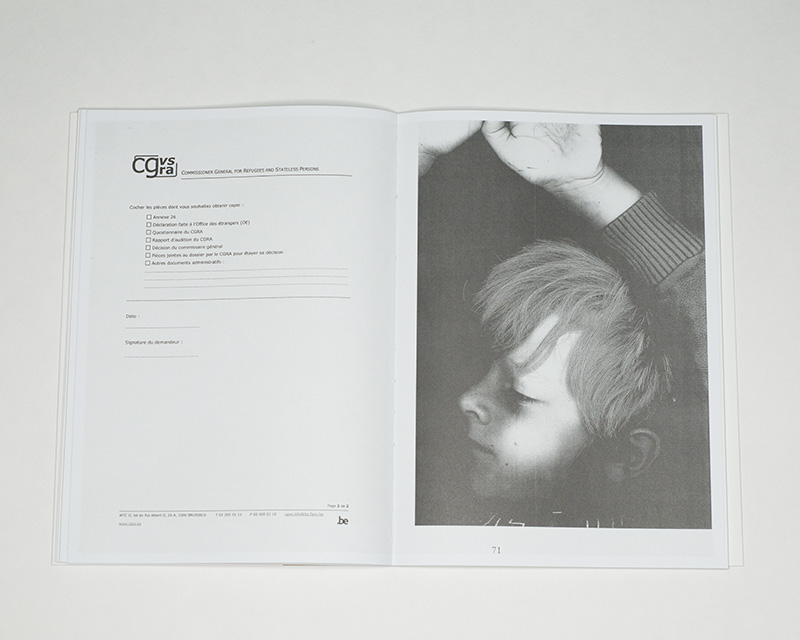

Interestingly, there already exist other modes of engagement with photography by artists such as, for example, Wendy Ewald or Jim Goldberg. A recent example that directly deals with Europe’s migrant crisis is provided by Maroussia Prignot and Valerio Alvarez‘s Here, Waiting. The duo spent an extended amount of time in a Belgian asylum seekers’ center, the kind of administrative limbo that is so common all over Europe (well, in those countries accepting asylum seekers; various countries have been refusing to fulfill their legal and moral obligations out of sheer xenophobia, if not outright racism).

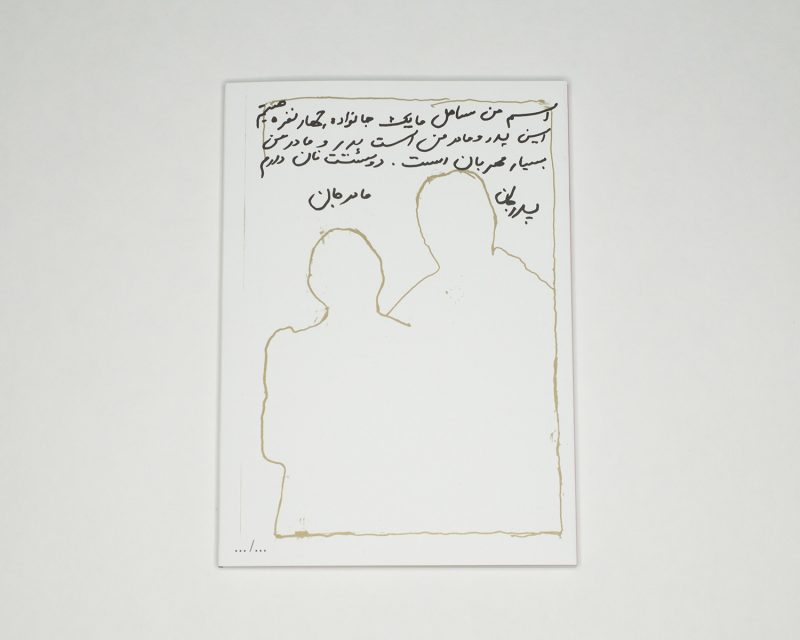

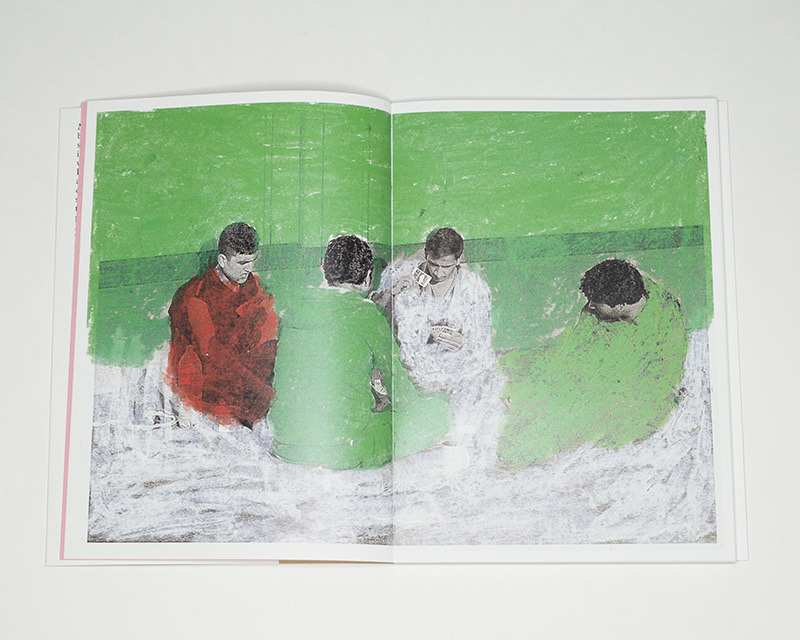

In the center, Prignot and Alvarez not only became acquainted with the center’s inhabitants, to document them and their living conditions, they also produced a series of workshops. The workshops were image centric. Photographs were made and printed to then be drawn on or modified by the subjects. A xerox machine, still a frequent bureaucratic tool, was used to make images like a scanner. Photographs were xeroxed and then drawn on. You get the idea. Whatever you want to say about photography having become a digital medium, the possible tangible nature of the medium played one of the most important roles in the process.

Here, Waiting is a compilation of some of the resulting images, in effect a mix of how the photographers came to see their subjects and how the subjects saw themselves — or maybe more accurately: wanted to be represented visually.

There are two dominant and very distinct strands of imagery that stand out. First, there are the many images of and by children that were drawn or drawn on and that at least right now provide possibly the only way for migrants to reach audiences in their target countries. While their collective plight has been amply pictured, typically only pictures of children make a (temporary) dent in the West’s callousness, whether it’s Alan Kurdi’s dead body, Yanela Sanchez crying at the border, or others. The second major group of images centers on young men, who are often depicted playing sports or being in the gym.

It’s doubtful that the book will change anything in Belgium or beyond. Those famous pictures of the children barely did. But to demand so much from photographs (or books) really is only an extension of the thinking that sees photographers as genius makers or truth tellers — after all, with such geniuses or truth tellers behind pictures isn’t it logical to consequently expect big changes as an outcome?

An alternative — I would argue much better — approach is the one that acknowledges that photographers’ subjects can be given an active role and that moves away from determining the validity and/or value solely based on the actually rather narrow ideas that are predominant given the established history of photography. Photographs can be precious in all kinds of ways — not just the ones that derive from photoland.

It is exactly that preciousness, plus the actual engagement Prignot and Alvarez brought directly to those trapped in Belgium’s bureaucratic limbo, that alludes to photography’s power. Photography is a way to recognize someone, especially if there is a deeper engagement, an engagement not merely based on passive consent but on active collaboration. In a very obvious way, the workshops provided a creative outlet for its participants. Beyond that, though, there was a direct exchange between two groups of people held apart by the state.

Even where the cruelty is not the point (such as when migrant children are separated from their parents and then held in cages), the bureaucratic procedures set up by modern nation states to “process” asylum seekers ultimately are inherently cruel. The mere depiction of fences and those fenced in will not change anything; but a direct interaction between the two sides of the fence will, whether it’s these workshops (or similar workshops held elsewhere such as in Warsaw), migrants and locals preparing meals together, or whatever else.

To stick to photography, it’s not the pictures that change the world, it’s the joint making of pictures that does.

Here, Waiting; images by Maroussia Prignot, Valerio Alvarez, and unnamed collaborators; essays by Julián Barón and Nicolas Prignot; 144 pages; Art Paper Editions; 2019

(not rated)

Ratings explained here.