Some of the world’s most virulent anti-migration populists originate from countries that without migration wouldn’t exist in their current forms, let’s say Hungary under Orban or the US under Trump. In fact, if you erased all forms of migration from history books, you’d end up with a book filled with blank pages — or rather, history would look a lot different, with homo sapiens never leaving Africa (who knows what might have happened elsewhere).

Some of culture’s most beloved heroes were also migrants (or refugees or both), such as Chopin who was born in Poland (another country currently ruled by such populists) but worked in Paris or the entirety of the US’ so-called Founding Fathers. Photography itself would be unthinkable without the contributions by migrants/refugees. For example, André Kertész was born in Hungary and migrated not just once, but twice. Robert Capa was born as Endre Friedmann, also in Hungary, before he essentially followed Kertész’s trail, albeit for different reasons. Robert Frank was born in Switzerland but his claim to fame is not called The Swiss but The Americans. Walter Benjamin who wasn’t a photographer but whose writing about photography still is very widely read wasn’t as fortunate. Attempting to escape Nazi troops (he was Jewish), he committed suicide at the French-Spanish border in 1940. Thus, in light of its own history the world of photography has every reason to be particularly sensitive to the plight of migrants or refugees.

Of course, migration is notoriously hard to photograph because it is a symptom of a complex set of circumstances that play out in at least two locations at the same time, a migrant’s (or refugee’s) place of origin (home) and the place s/he hopes to reach (a new or at least temporary home). Most photography I am aware of centers on the actual process of migration, with often vast groups of people moving on foot, crossing or attempting to cross borders. That obviously makes for good fodder for photojournalism (at the time of this writing, John Moore’s photo of the crying refugee girl from Honduras is nominated for a World Press Photo trophy). Almost inevitably, though, these photographs don’t get at any at of the larger underlying issues, nor do they actually help fix anything (“Since the Trump administration announced it would end its practice of separating families apprehended at the southern border last June under its ‘zero tolerance’ immigration policy, at least 245 children have been separated from their parents, according to a new court filing.” reported CNN on 12 February 2019).

On their artier side of things, the technological overkill produced by Richard Mosse won the artist a Prix Pictet. Since I finally saw the video installation last year, I have even more concerns about the work than when I wrote about the book. Before that (and way before the arrival of hundreds of thousands of migrants/refugees in Europe), Henk Wildschut had approached the topic by photographing a large migrant camp in Northern France (there’s an updated version as well). These examples aren’t intended to fully cover how photographers have been attempting to deal with migration. The topic is quite old, and one can easily find a lot of older examples (such as, for example, Jim Goldberg’s Open See — which also won one of those awards, or the now curiously overlooked The Seventh Man by John Berger and Jean Mohr).

And then yet another migrant project won an award, the 2018 Kassel Dummy Award, in the form of Michael Danner‘s Migration as Avant-Garde. So I had a peek. Obviously, the worst way to look at many photography projects is to visit the website. I’m using the word “obviously” here, even though the book had to actually remind me of what I should have kept in mind. On the website, the pictures are presented as a hodgepodge of the types of photographs that many artists produce these days. That fact, plus the title, had me on edge, because if anything migrants or refugees ought not to be fodder for any photographer’s attempt to produce something overly arty.

It was seeing and experiencing the book that made me realize the value of the work. To begin with, the book demonstrated what can be gained from organizing photographs into this type of linear form that a viewer holds in her or his hands. This is an obvious statement, but pictures that shouldn’t be seen next to each other won’t be seen that way in a book. In addition, the overall organization of the visual material allows for a structure that helps communicate the intent. Most importantly, though, there are quotes by Hannah Arendt interspersed in the book, herself a refugee at some stage. These quotes give voice to the migrant/refugee experience and, crucially, they provide the context within which the book’s title itself can be understood.

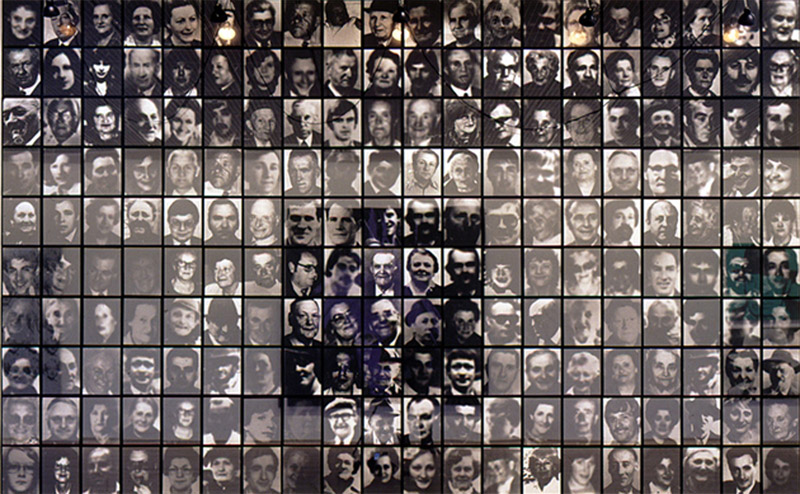

Migration as Avant-Garde attempts to cover the topic at hand from as large a variety of angles as possible, while avoiding the kind of visual fodder that dominates the news and that is so useless to understand anything. The pictures that on the website look so much like New Formalism exercises merge into the overall story, adding elements of visual delight as much as distancing (in the Brechtian sense). The fortress that Europe has constructed at its edges becomes clearly visible. It is the very last section, though, photographs of people who the viewer is made to think underwent the trek to Europe (there is no text) that really seals the deal (their names and origins are given by the artist in the afterword). They are shown as fully-formed individuals who possess as much a sense of personal agency as everybody else (contrast this with the way both photojournalists and artists like Richard Mosse visually dehumanize migrants/refugees to focus solely on photographic or artistic effect).

Obviously, the Kassel book festival has a lot less visitors than the various venues where World Press Photo pictures are being shown, and the same is true for photobook stores (where they in fact exist). It’s too bad that John Moore’s photograph of the crying girl will be seen by a lot more people than Michael Danner’s thoughtful exploration of what migration might really mean. That’s the fate of photography as art versus photography as news fodder/news click bait. But maybe the book will find itself in the hands of just the right people to serve as a starting point for discussions about not only what art can do, but also — and in this context especially — how slowing down and allowing for more nuance is something our societies desperately need. We owe that to ourselves as much — or maybe even more — as to those who reach our shores, often for the most desperate of reasons.

Migration as Avant-Garde; photographs by Michael Danner; text by Hannah Arendt; 120 pages; Verlag Kettler; 2019

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.0