Photobooks aren’t the only types of books arriving at my door step. There are also books about photobooks or about photography in general. The following discusses three such books that I recently engaged with.

I initially approached Mark Alice Durant‘s 27 Contexts with the wrong mind set, having misread its subtitle as “an anecdotal history of photography” instead of “… in photography.” I’m not sure what I would have expected to find had I paid more attention. I’m not even sure I would have approached the book differently. But my misreading provided yet another reminder that every book that I encounter is not necessarily treated on its own terms. Instead, I approach it with my own preconceptions in mind, however much I might attempt not to do so.

Not to get too hung up on the differences between two characters that form two very short words, but Durant’s book in fact is also what I thought it would be, an exploration of photographs against the background of the author’s biography. Mostly, though, the focus is on the private and professional life itself and the photographs arising from or directly connected to it. It’s a life that started in a suburb of Boston, moved all the way out West, and is now back on the East Coast in Baltimore.

Much like any artist’s life, Durant’s has been filled with ups and downs. A creative life wouldn’t be one without periods where it’s anything but that, creative, periods where things appear to be falling apart more rapidly than they can be put back together again. Much to his credit, Durant does not shy away from including what others might have been tempted to exclude.

There is a richness to the experience of reading about this particular life, as presented by the person living it, a richness that often is absent from other such books. This richness is not just due to the fact that Durant is an excellent and engaging writer. For me, it also arises from suddenly becoming interested in, let’s say, the kind of performance art he was engaged in for a while or from seeing certain photographs discussed under a different angle.

Thus, 27 Contexts isn’t “just” someone’s autobiography (let’s just call it that). It is such a chronicle against the vast background of this larger cultural medium that surrounds us with images, while we make some ourselves. We can’t help but act against this background. But most of us aren’t as conscious of what we’re doing and what we’re exposed to. To be able to read about how certain photographs imprinted themselves on this particular biography makes for the finest reward this book has to offer – and it might nudge us towards paying closer attention to the visual backgrounds of our own lives.

I’m extremely skeptical about many ideas of collaboration that are being floated in the world of photography, especially when it comes to portraiture. So it would seem that Daniel Palmer‘s Photography and Collaboration was not necessarily written for someone like me. But I’m also very eager to get my horizon and thinking expanded, and what better way to do that than to have someone make an in-depth case?

Thankfully, Photography and Collaboration goes much beyond the idea that all portraiture is collaboration. Instead, it dives deeply into the history of photography to discuss a series of artists with this particular approach in mind: to what extent is their work based on some form of collaboration, however explicit or implicit it might (have) be(en)? This discussion of history happens in two separate parts. The first, covered in the first chapter (“Ideologies of photographic authorship”), provides a terse run across the medium’s larger history, examining various aspects. To be honest, I wasn’t sold on much in that chapter.

The book’s real meat, however, is provided by the remaining chapters, “Photography as readymade,” “Photography in the name of community,” “Photography as social encounter,” “Found photography and social networks.” In each of these chapters, three artists (or groups of artists) are discussed in detail following the larger framework. These sections are well researched and can easily serve as introductions of the artists in question in their own right.

Investigating an artist with the idea of collaboration in mind can make for very interesting insight. It might be obvious why and/or how Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin collaborate, but how is, let’s say, Joachim Schmid potentially collaborating with those whose pictures he finds? On top of that, the usual suspects here mix with artists that aren’t discussed as often as they should or that maybe usually exist in different contexts (think Douglas Huebler).

I’m not sure that the work of all of the artists discussed in the book is at the same artistic level. But to insist on that would surely miss the point (and tilt the book back towards the same old usual suspects). Instead, Photography and Collaboration offers a way to (re-)engage with artists under a very specific angle, namely to what extent their work relies on or works with outside input that usually is just swept under the rug.

It would also miss the point if a reader (like this one before he read the book) would insist on agreeing with the author on every single point (I still don’t believe portraiture is a form of collaboration). Palmer’s larger point is to open up our thinking around art as that activity solitary, isolated human beings engage in, to put it back into the larger world we all – including those artists – live in. If anything, in our hyper-individualized world that’s an important point to make.

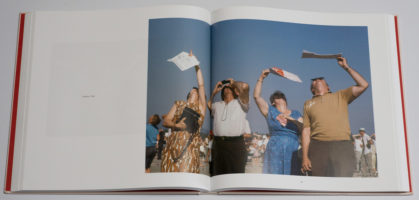

Magnum Photobook by Fred Ritchin and Carole Naggar is billed as “the catalogue raisonné.” And the book does indeed provide a listing of all photobooks ever made by all Magnum photographers at its very end. The list of photographers includes everybody who ever was part of agency, whether they stayed or not (if I counted this correctly, that’s 85 men and 11 women). That’s a lot of photographers making a lot of photobooks (also, that’s really not a lot of women).

The larger, main section of Magnum Photobook covers examples of these books – one per photographer, Parr/Badger style. One could possibly have a debate concerning which book was selected for each photographer (for example, I’m baffled by seeing Chris Anderson’s Stump and not Capitolio). But at the end of the day, such a discussion might not lead anywhere.

The larger question appears to be what actual insight is provided here. Actually, I’m not sure. What we learn is that Magnum photographers have made books (some of them a lot), and the sum of these books adds up to what you might imagine it does, considering the agency, while successfully living off a reputation established over 50 years ago, now is a fairly amorphous group of photographers that reflects the world of photography at large, at least how it’s currently established in the West. What does this tell us, though?

In terms of the books, there isn’t much more to learn, either. How can you even compare, say, Philippe Halsman’s Jump Book or Martin Parr’s Common Sense with Philip Jones Griffiths’ Vietnam Inc. or Abigail Heyman’s Growing Up Female? The answer is obvious: you can’t. The former are shallow entertainment, and the latter are anything but that. This is not to say that there’s anything wrong with the idea of this book. On the contrary. It’s about as good as a taxonomy of Magnum photographers’ photobooks could get.

But maybe what is to be learned is the following. For any such meta-book to offer insight it has to go beyond these very broad kinds of categories that are being used left and right, whether they’re geographical or whatever else. Let’s face it, the good books about photobooks aren’t good because of their categories, they’re good because in those categories such great material exists. Where the material is as mixed as it is in the case of Magnum photographers, you end up with, well, something like this book, especially given all these very different books are presented with equal weight. That’s good for crossing the bar provided by the main idea – a catalogue raisonné of Magnum photobooks. But beyond that, for me it’s really not terribly interesting at all.

There are enough photobooks here, to give just one possibility, to look at the evolution of the photojournalistic photobook in more detail. The photographers obviously aren’t the same, but with each new generation there appears to be a push towards a slightly different form. Obviously that’s a different catalogue raisonné. It’s here where I see most of the potential of the book about photobooks. The librarian’s approach has given us Parr/Badger etc., and that’s great. Now, I’d like to see more in terms of depth, a depth that a simple survey just can’t offer.