If you’re paying any sort of attention to the news, you will be aware that leading up to this year’s US presidential election, the so-called primaries are happening. Even now, despite the fact that a lot of them already dropped out, there still are plenty of candidates. And there is an abundance of stories and narratives around them, which might or might not reflect what’s actually going on. M. Scott Brauer has spent a lot of time photographing these primaries, and I thought that would make for an interesting conversation. Much to my delight, Scott took time out of his busy schedule to answer some questions. Grab yourselves a cup of your hot beverage of choice, and enjoy his fascinating take on the primaries — and photography — behind the scenes of politics!

Jörg Colberg: In this day and age, democracy seems to revolve as much around the fact that there are elections as that these elections are portrayed in very specific ways. From what I can tell, most political campaigns spend considerable efforts on trying to make sure the right kinds of pictures are being produced, so that their candidate is presented in just the intended way. There are plenty of flags, and candidates giving speeches often use very clearly selected people as backdrops – Count Potemkin would recognize all of this well. As a photographer, how do you approach photographing such events?

M. Scott Brauer: From the beginning of the project I knew I wanted to do something different from the coverage of political campaigns seen in most newspapers and magazines. I’d photographed the primary a little in 2012, but with a very straightforward style. The work didn’t excite me, and I spent a lot of time in the first part of 2015 thinking about exactly why that older work wasn’t interesting to me. I come from the American newspaper and magazine photojournalism traditions and shot it with that sort of natural-light, fly-on-the-wall approach. But looking back at the work, I find it doesn’t reveal much about the political process.

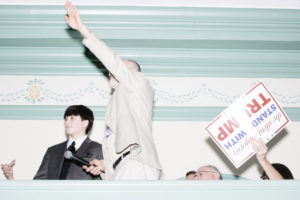

These campaign events are essentially press releases with everything perfectly arranged to present the candidates in (sometimes literally) the best light possible. There’s so much that goes on behind the scenes at these events, and that’s hard to see when the focus of attention is lit 3 or 4 stops brighter than anything around them or when the flag or people background behind the candidates is arranged just so. Thinking about this all, I knew I needed to counteract their lighting, figure out ways of shooting around the pre-determined set-ups, and also get a wide-enough depth of field so viewers could get a better idea of the environment surrounding a candidate. There are also really interesting moments before the candidate steps on stage or after they leave an event. There’s a legion of staff that makes sure the flags or banners are just perfectly positioned, for instance. Even with the lighting, these events are often really dark. Photographers have to use low apertures making everything but the candidate a soft, attractive blur. And looking at the images on candidates’ campaign websites, that’s exactly the sort of image they want to present of themselves: a patriotic hero standing in sharp focus in front an American flag or diverse collection of supporters.

I started the project with all of that mind, wanting specifically to subvert the images that the campaigns present of themselves. That doesn’t mean I don’t shoot the podium shots, but I realized I needed to make those podium shots interesting and informative about the process of modern American politics. I look at the project as not being about the specific candidates or the parties at all, in fact, but rather about the overall process of politicking. A good portion of these candidates’ appeals to the public is to show just how in touch they are with “real America” or “working families” or whatever the term they use is. But there is nothing less authentic than these campaign events. They are rehearsed and stage-managed and designed and focus-grouped to be almost infinitely repeatable. I’ve heard Ted Cruz tell the same joke at 6 or 7 events in the past month, for instance. It seems like Donald Trump just switches around a few superlatives at each rally. Sanders will hit the same 5 or 6 points about wealth inequality and climate change in every single speech. Hillary Clinton has something like a 45-minute playlist that plays “Happy,” a Jennifer Lopez song, and a couple others on repeat for a couple hours before each event. Scott Walker squinches up his nose in exactly the same way in the instant before every time he smiles. It’s a bit like Groundhog Day, but unless you’re really paying attention, it seems like each speech or meet-and-greet is a unique event. The attendees might feel like they’ve had special access to a politician. TV viewers see only a snippet or two, even if they regularly watch the nightly news, so it all seems novel. The reality, though, is that almost every moment you’ve seen in the news or at an event has happened over and over and over.

My approach to these events is thus a bit different from the way I approach a lot of the projects I shoot. I’ve got all of the above in mind, so I’m looking for cracks at the seams, repetitive elements across events or candidates, expressions and gestures by attendees or the campaign that belie the excitement and patriotic front that is put forward, etc. And I’ve singled out a few ideas that fit my conception of the primary being the worst party I’ve ever been to. This is a radical departure for me. I’m never one to make lists of what I need to shoot for a project and am happy to just let the subjects or story lead me however it will, like unravelling a sweater by pulling on a loose string. With this, it’s like the sweater’s pulling back, always trying to maintain its form. I’m trying to show that the sweater isn’t really a sweater at all, so I’ve got to keep pulling at my idea. It’s risky to let the idea shape the story. I don’t want to let my idea take over. I feel there’s an honesty to the way I’m photographing this, and if I let the idea guide me too much, I lose that honesty. The work might become untruthful, mean, or parodic.

JC: Those primaries and election events would really not work at all any longer if they weren’t also broadcast, in whatever form. So it’s kind of a dance, and for most dances you need more than one person. “The Press” – photographers, journalists, etc. – clearly are that partner, and there clearly is another agenda at play that is not quite independent of the campaigns’, but that follows different goals, goals that often somewhat openly work around a preconceived narrative around a politician. Is that something you think about before starting to work? Do you consider your own biases or ideas, or your peers’?

MSB: You’re right. The whole point of all of American politicking is to get on TV news and in the papers. The candidates depend on exposure afforded by mainstream news coverage and, as Trump has pointed out so much recently, the networks depend on this whole show to bring in ratings and, thus, ad revenue. I mean, the 24 hour news networks would still be blathering on even if there weren’t an election, but the campaigns give them so much more meat to carve up.

There’s a really weird thing that happens between journalists and politicians, too, as regards access. At the beginning of the campaigns, the candidates want every journalist they can get. But when they’re at the head of the polls and every journalist wants to cover them, the candidates can be a little choosier in who they let ask questions or get exclusives or even get in the door to an event. You see this much more when politicians are actually in office and they’ll dole out access or off-the-record comments to journalists that they like, and cut off access to those who the politicians perceive as having reported wrongly or unfairly. The journalists need access so they can write stories, so they might pull some punches. There’ve been plenty of stories of Trump kicking reporters out of events. Many candidates, especially when they get more popular, will set up pool coverage of their events. That means only a few reporters are allowed in and other publications must share their reporting. It makes sense when the event presents difficulties to covering like normal. Courtrooms, for instance, will have pools because the space is usually very small. On the campaign trail, the small business stops will sometimes be pooled just because there’s no way to physically fit the whole press scrum in, especially for a candidate like Clinton or Trump. Sanders’ campaign did some pooling at a couple of events in December that journalists thought was unreasonable and it resulted in less coverage of his events. One event was in a barn, and there’s always a way to fit more people into a barn. But the campaign wanted to pool it, so many of the journalists just refused to cover it.

There’s a documentary called “Spin” about this. It’s a look at the 1992 campaign almost exclusively through raw satellite feeds. In it, you can see the relationship between journalists and politicians. You can see how repetitive the “satellite tours” are. You can see how the candidates immediately turn on their personality when the live broadcast starts and how they turn it off as soon the broadcast stops. It’s fascinating.

The reason that I bring this up is that the give and take between politicians and journalists, which is generally doling out access depending on the favorability of coverage, has no factor in how I’m covering this. I almost never shoot politics; none of the images for this project are from private events; I don’t depend on access to politicians for my future work as a journalist. As I’ve said, I’m not trying to do a hit-piece on any person or party, but I also don’t want to pull any punches. My position as a journalist whose work does not depend on politics means that I can take more chances with my work. If, for some reason, every current and future politician denied me access to photographing their campaigns, it would make no difference to my career or bottom line. I can take risks other political journalists can’t afford to.

As I’d mentioned above, one of the main reasons for starting the project was my dissatisfaction with most political photography. I don’t mean to denigrate the wire photographers or anyone else covering politics. There’s a value to the work they do. Newspapers around the country and world need that sort of work. It’s important for the historical record. But many people are already doing that type of work, so there’s no reason for me to do it. There are valid complaints about the amount of press coverage certain candidates get, but I don’t think individual photographers should be blamed for that. All the photographers I work alongside at these events are great at what they do and cover the events in fair and interesting ways. Quite a few are working on little side projects that are pretty interesting – maybe portraits, maybe still lifes, maybe multiple-exposures, maybe something else – but it’s not the work that their employers/clients want. The newspapers have to observe a level of objectivity (I know that’s a sticky issue that you’ve covered here previously, but you know what I mean), and there’s just no room for certain types of photography. And sometimes, perhaps, some interesting work has been shot and even submitted to the photographers’ clients, but it just won’t work with what the publication can or wants to do.

Here are a couple of stories that speak to these issues, I think. In 2012, I did a behind-the-scenes assignment on a campaign for a big, international newspaper. The idea was to get me behind the scenes on both the Republican and Democratic campaigns in the race. The editor wanted to do a nice display in the paper and run slideshows online. The Republican side gave me full access, but the Democratic candidate wouldn’t. I spent a full day with the Republican and had enough to do a nice slideshow and a big spread in the paper. But because the Democrat wouldn’t let me in, the paper didn’t want to publish all of my work for one candidate and then just grab some wire photos for the other side. The end result was that only a single picture from 8 or 10 hours of shooting was ever published. I completely understand why; the paper needed to show balance in coverage and it couldn’t.

Specifically in this project, take a look at this picture of Ted Cruz. On the left of the frame is the arm of a great newspaper photographer. We’d been talking before the moment happened; he saw it happen and got a little ahead of me to take the picture. But after a frame or two, he put his camera down and said, “They’ll never run this.” On the other hand, that picture led the portfolio of the project that Esquire just published in the February issue. Different publications have different tolerance for different sorts of images and approaches.

As for my own bias, I’m lucky that I don’t have any of the pressures of the desires and sentiments of editors or publications to influence my coverage. Few photographers have that luxury. As of this writing, in fact, I’ve had just a four days’ assignments in the 6+ months I’ve worked on the project. There was an exclusive with Donald Trump for the Wall Street Journal; there was a day photographing campaigns for Businessweek; and there was two days for Time. For the WSJ, I knew the editor was interested in the way I’ve been shooting the project, but I also know that the paper has a certain style of coverage, so I tried my best to fulfill both my own interests in shooting the subject, and the paper’s. But other than that, it’s been totally free rein. That freedom raises its own complications, though.

I was really worried about the project during the first month I’d shot it. I was recovering from a badly broken arm, was planning my wedding, and I had regular assignment work keeping me busy. Because of that, I could only get up to a few events here and there, and they all happened to be Republican. At the time, there were 17 or so declared candidates and my work really fit the prevailing “clown car” narrative about the Republican field. I didn’t want this to be a hit piece on the Republican party, and not having covered any Democrats’ campaign events in my career, I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to photograph Clinton or Sanders in the same way. I think I photographed Sanders first, and I immediately knew it would work. It was in a weird wood-paneled room and there was just as much bunting as any other candidate’s events. Sure, there’s a little more tie-dye at the Democrat events, but otherwise, they’re basically like all of the Republican campaign stops. I’d mentioned earlier that this project is meant to critique the political process rather than individual candidates or political parties. The process is basically the same on both sides of the aisle: bad music, some patriotic decorations, bored staffers on the sidelines, pleas at every event to donate and volunteer, similar graphic design on the campaign signs, etc.

The other thing I’ve been worried about is losing my critical perspective as the months wore on. Just a few weeks into the project, people started coming up to me and saying they’d seen me at another event, and soon I started recognizing people, too. I started to know all the other journalists on the beat, and I developed friendly relationships with some on the campaign staffs. I know it’s not the same, but I’ve read about the bias resulting from embedded war reporting, and I was worried about something like that happening. I was worried that maybe I wouldn’t photograph a poorly-placed campaign sign, for instance, because I knew the person who’d put it up. Or perhaps I wouldn’t be as aggressive in my coverage of a particular candidate because I’d decided they’d be getting my vote when my state’s primary comes up. Or perhaps I’d be too aggressive, making a certain campaign look bad because I’d been treated poorly by their staff or I didn’t like something they’d said.

But after covering this story for so long, I feel like I’ve been fair across all of the candidates. To be honest, it all actually runs together. I was talking with an editor this week and they wondered what I’d been photographing recently. I mentioned a couple candidates and then said I knew there were a few more but couldn’t actually remember. When I’m taking pictures of these events, I have a hard time paying attention to what’s being said. And after a while, everything at one of these campaign events feels more like a still life than anything else. Maybe still life isn’t quite right. I was talking with another photographer recently who’d been covering this but wasn’t all that interested in politics. One of us said that it felt like we were aliens observing humans going through some strange ritual we’d never seen before. That’s really what it feels like after all of this time. I guess that’s what the project was meant to show: all the things involved in these events (the candidate, the audience, the signs, the decorations, the music, the food….) are really just props. After working on the project even just a few weeks into it, everything had turned to props in my own mind, too.

JC: When we throw all of this together, especially in light of what you just said, it isn’t quite clear to me what anyone possibly gains from this whole spectacle. Through all the control and mediation it seems so far removed from the underlying ideas of what eventually is at stake. I read Ben Cramer’s 1993 book What It Takes, and I couldn’t escape the impression that the combination of campaigning, plus of dealing with all of this stuff, is completely grueling for everybody involved. Being a part of this all so frequently, how do you deal with what it is, how it relates to your normal life? How do you decompress?

MSB: Well, this is really the first time I’ve covered politics so extensively. Everyone always comments that it’s got to be grueling or boring or exasperating (“How can you stand to be in the same room as Ted Cruz,” one side will say. Or, “I couldn’t stand 10 minutes of listening to Hillary talk,” from the other). This is just another project and it’s pretty rare for me to get tired of something I’m shooting. I haven’t tired of it yet, and sometimes I’ll cover 4 or 5 campaigns in a day. I’ve been doing that for 6 months. The final week before the primary started to get difficult. 7am to 11pm or so each day with a lot of driving and always feeling like you’re missing something. I’m lucky that I rarely have deadlines to worry about or editors looking for something specific. I also can just pick and choose what I cover, so if I need a break, I’ll take a day or a week off. I’ve been shooting a few assignments a week for years now, so it’s not really different from my normal work.

There is one thing that really bothers me, though. Those patriotic country songs that every candidate plays before and after events have a way of making me hate everything. Recently Sanders had a Bowie song playing after one of his speeches. That was a nice change. And when I’m driving between events, I’ll listen to podcasts or music that I really like to cleanse my palate a bit. Thirty minutes of listening to Warren G or Laura Veirs or Miles Davis or Hardcore History really does wonders.

One thing that has been difficult is the sheer amount of pictures I’m taking. I’m not sure I’ve ever photographed a single project or subject so heavily. And then there’s the editing, captioning, other post-production (really minimal, but the time adds up), uploading, and then sending out to publications. It takes hours and hours and I have a huge backlog. It’s also been really difficult to edit through the work after the fact when working with publications or thinking about contests, calls for entry, and the like. It’s a daunting task and I’m not sure I’ve succeeded at it yet. I’m in a weird space between the daily photojournalists and other sorts of photographers. I don’t have deadlines, but there’s also a short shelf-life during which this work will remain relevant for the sorts of publications I typically work with.

JC: So what will the “end product” be? I mean, given all the work you put into this, given a different take should be seen by a larger number of people, and given most media outlets are as you said unlikely to publish the work, will you produce your own publication? But then, given the photobook market is such a tiny niche, how would it reach a somewhat larger audience?

MSB: That’s the big question. My interest in taking pictures is always in getting them out to an audience, no matter how small. If my pictures are just sitting around filed away on a hard-drive, collecting dust, I’ve failed in my goal. When it comes down to it, the reason I pick up a camera is to tell a story to others about the things I’m photographing. Some projects are more successful than others at that, but that’s always the goal. I’ve been lucky with publications wanting to take a risk with this. Esquire published an 8 page portfolio in the February issue and also online. The New Republic recently did a big web piece and will have something in print in the March issue on newsstands now. Time used a few photos in print and online and published a story we worked on about Jim Gilmore’s long-shot campaign online. Le Monde’s weekend magazine ran 5 pages of images for a Trump story, and Canada’s The Globe and Mail did a nice doubletruck for another Trump story. New York Magazine’s political blog, The Daily Intelligencer, ran some pictures. The Wall Street Journal ran a couple pictures shot on assignment in the style of the project with an exclusive interview with Trump both in print and online (I did shoot some natural light on that just in case the editors didn’t want to run this weird sort of coverage; there isn’t much in the WSJ that looks like these pictures). Blooomberg Businessweek did a spread. I’ve been sharing pictures on my Instagram and Tumblr, which together equal around 35,000 followers (though who knows how many actual people that reaches). There was a great MetaFilter post about the project with good discussion from people outside the photography and journalism worlds. I did an interview with The Image, Deconstructed and now this piece with you.

By circulation/readership size of each of these outlets, that’s probably at least 3 million viewers who have at least seen snippets of the project, which seems like a a pretty wide reach for my strange perspective on American politics. I’d love to do a book or exhibition or something, but lately I’ve just been focusing on shooting the project since it’s there is such a short, fixed time in which to shoot the project. Now that the primary is over, hopefully I can think about this a bit more. You’re right, though, that photobooks have such a small audience. But each method of getting work out to the public has a different audience, not necessarily overlapping. Each of those outlets I mentioned above reaches different people, and that’s what I’m after. I had a project China’s zoos published on Buzzfeed last year, for instance, and I was getting emails from 15 year olds around the world who were inspired by the work. Pieces of it had been published before, but the other places that published it would never reach those 15 year olds. Interviews like this reach a radically different audience from the magazines that have published the work, too. I think I’ve done a decent job getting the work out so far, but there’s always more to do.

I’m also curious what life this work will have after the primary and especially after the 2016 election. It will lose its news value, of course, and my pictures probably don’t have the same historic value that the AP’s coverage has. These will never be the pictures printed in textbooks along a blurb about Hillary Clinton. But I hope what I’m trying to say about the political process through these pictures will have some value, even when these particular candidates no longer have national and international relevance.