A spectre is haunting photoland — the spectre of audience. In some way or another, it appears to pops up its head everywhere. In an obvious sense, discussions about so-called social media center on the question of how to build and grow your audience. Given many (most?) of those discussions tend to be self-referential there often is little to be learned there, though: to what end is this being done?

Colin Pantall has recently been writing a lot about photobooks and their audience, that niche group of people I belong to as well. An aspect of it is the photobook festival, which to me at least increasingly looks like the same small group of people traveling from location to location, staging essentially the same festival only in different locations (much like a circus — feel free to think about who the lions and who the clowns are). Offprint here, Offprint there, Offprint everywhere. Don’t get me wrong, in principle I like the idea. In practice, however, I’d like to think that the goal should be to grow the audience for photobooks, and I’m not sure that’s happening.

And just the other day, I came across an article by Michael David Friberg. “We spend thousands of dollars and years of our lives on projects,” he writes, “only to publish an expensive photo book that will probably only be seen by a handful of other photographers, editors and photo geeks etc etc.” This obviously overlaps with the preceding. But there’s more: “The incredible myopathy of our industry is staggering when you think about it. We have been looking in all of these pre defined spaces for validation when they are in all reality, probably not the best ways to disseminate work.” (my emphasis)

In some sense, Friberg is wrong. These myopic outlets are the best ways to disseminate work: they’re easily available, and there is an audience, however small it might be. But the real question is whether that’s the audience we all want to play to, and that’s Friberg’s actual point here. Should the following scheme described by Friberg really apply? “Grant applications (that you won’t get) > project work > pitching the project > maybe a magazine runs a few of the photos in print > runs in a big fancy photo blog > published in a limited edition of 500 monograph > gallery show > goes on your website to die.” (depending on what part of photoland you operate in, your version of the scheme might omit a few parts)

In other words, what looks like the most obvious way to reach an easily available audience, however small it might be — is that the way to go? Or are there alternatives?

Isn’t it a bit absurd that photography currently is one of the most popular media, maybe even the most popular one, yet large parts of the people engaged in it in a professional manner operate in a miniscule niche that for the most part is completely invisible to all those who happily snap photographs with their phones and tablet, and who then share those pictures and look at other people’s pictures? How can this be? Or rather: can we change this?

There probably are many ways of thinking about audience. I could be entirely mistaken, but it seems to me that many photographers think of their audience as whatever section of that pre-defined, already existing audience in photoland they can get. And audience is thought of as an afterthought. You go about your work, and then, once you have the end product, you think about your audience. That might not be the best approach.

The more we think in terms of fine art, the more problematic thinking about audience becomes. If you worry too much about your audience, in particular what to do for that audience, you risk catering to an audience, reducing your art to essentially being entertainment. Per se, there’s nothing really wrong with it, and some well-known photographers have been very successful with this approach. But the question what the end result amounts to often comes up with very little. The opposite approach would be to brood in your studio until it’s all done, and if people don’t like it, they can go to hell. Somewhere in between those two extremes, there have got to be other viable spots.

Assuming that as an artist you actually want to break out of the scheme outlined above, there are many options. You just have to start thinking outside of the box. You will also have to face the fact that if you want to engage with a new audience, things won’t necessarily be a huge success right away (they can be, of course).

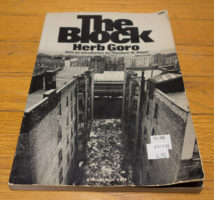

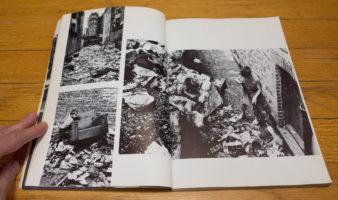

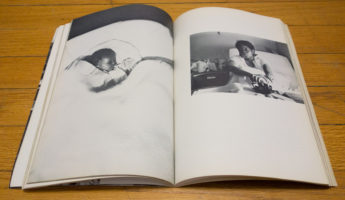

For example, if you want to make a photobook, does it have to be a photobook that targets the photobook niche, a highly specialized and stylized publication? Make no mistake, there’s nothing wrong with the photobook per se. But I feel that in its current form, the medium is being considered in oddly narrow, limiting terms.

In much the same fashion, you can exhibit your work in ways other than the white-cube gallery, which usually really is just a boutique for the well off.

I’m not sure to what extent photographers consider these kinds of questions. I’m not saying they have to. But those who are not content with operating in a fairly small niche, one whose cards are pretty firmly stacked against most of those interested in getting a piece of the pie — those photographers might want to consider different ways to reach an audience. An audience, not the audience. And this would have to start out with the work, the photography itself: who might be interested in this? And how can those people be reached, regardless of whether they’re part of the niche?

That might mean not traveling to Arles, for example. Don’t get me wrong, Arles is probably great (I’ve never gone). Photoland loves going there. But you probably won’t find any of that new non-niche audience there.

If you’re one of the recent graduates of any of the MFA programs, you’re likely to face that very question right now: where am I going to take things from here? Graduates often ask me how to approach publishers or how to get that gallery show… Are those really the only options? Are those options the ones that you want to be pursuing?

That photoland pie is pretty limited, and the crumbs you might be able to pick up here and there aren’t overly nourishing. Given there are more and more photographers interested in if not some big piece then at least some crumbs, it might be time to look for a piece of some other pie. And part of the work needed might be not to think of the audience you know, but about the audience you don’t know, yet.

(this piece in French: La question du public)

A couple of unrelated things:

First, my sincere thanks to all of those who contributed to my fundraiser! If you haven’t donated, you still can.

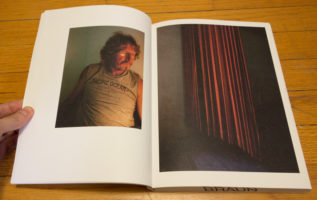

Also, I started producing video photobook reviews. There are two available already, one of H. said he loved us by Tommaso Tanini, the other one of Find a Fallen Star by Regine Petersen. They’re each about five minutes. Feel free to send me some comments so I can work on improving whatever needs to still be improved.