If you wanted to, you could divide the world into two parts. One part would contain all those people who are able to control the narrative that surrounds them and who for that reason are in charge of their own destiny. The other part contains all the rest of the people whose story is largely defined by those other people. From what I can tell a much larger fraction of the world is part of the second group. Despite (or rather because of) their enormous privilege, the first group resists changing this situation.

This basic situation plays out on a number of levels, ranging from what on a societal level is microscopic to what’s macroscopic. And it extends far beyond that as well. On the largest possible scale, entire countries are placed into one of these two categories. This fact can have gruesome consequences, as the inhabitants of countries who were or are defined by others know all too well. Colonialism would have been unthinkable without a racist definition being created around regions that were then plundered and pillaged by nations who carried the banner of their own supposed enlightenment.

The war in Ukraine entails not only a literal fight over land. A fight over the definition of what the country actually is forms an essential part of the war. Russia’s fascist dictator claims that there is no such thing as the Ukrainian nation, which somehow translates into a right for Russians to commit mass atrocities. Ukrainians, in contrast, are now struggling to not only survive but also to show the world that there actually is such a thing as a Ukrainian nation with its own very rich culture and history.

But the problem extends far beyond the two countries. More than three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, most Western European countries still have absolutely no understanding of the richness of culture and history between what used to be the Iron Curtain and the border of the country that replaced the Soviet Union as a major power, Russia. It’s probably more than fair to say that in the US such knowledge is even more limited.

For example, German news media still parrot Russian propaganda about Ukraine without even batting an eye. I don’t know whether they’re just clueless or they don’t care (I also don’t know whether the difference matters). And it’s not even Ukraine, whether it’s Poland, Hungary, Latvia or any of the other countries that lie between Germany and Russia — most Germans don’t care to learn more. This obviously isn’t only a German problem. But since I’m German, I prefer to get upset with my own people.

Even as art and culture have been assigned little to no value in our neoliberal world, you can still see their power by the frequent Russian attacks directed at Ukrainian art and culture. Even the most uncultured fascists know that a display of military power and might only translates into a very brittle narrative around a nation, one that topples with very little effort.

Especially if you are an artist (or writer [such as this one]) struggling to make ends meet, you want to remind yourself that there is a value to art that transcends prices realized at auction houses by a huge amount. You won’t be able to pay your bills with it, but you contribute to a larger good that cannot be assessed in financial terms.

Art can play an enormous role in building a narrative around a group of people or a country that corrects one imposed by other groups. In part, this is because good art does not make any claims regarding telling the full story. Instead, you tell your story. This leaves space for uncertainty and for discussions. That’s why such narratives are much longer lasting than those imposed by sheer power. The latter will crumble when challenged just enough. The former allow for openness and for adaptation; they are, in effect, human: full of truths and contradictions at the same time.

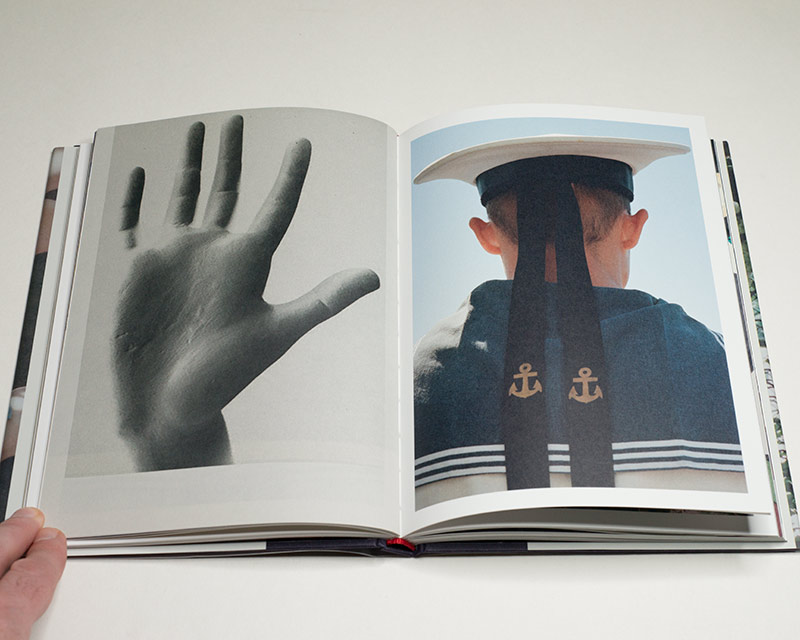

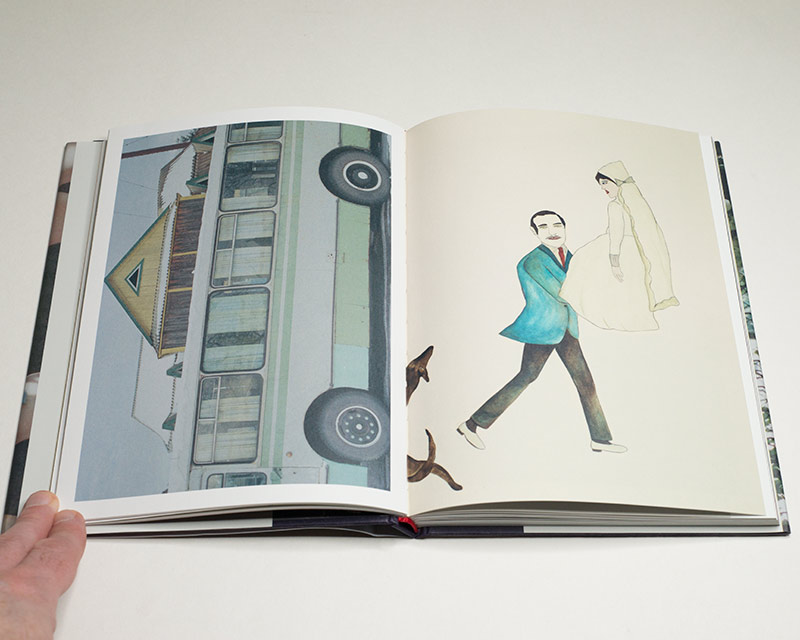

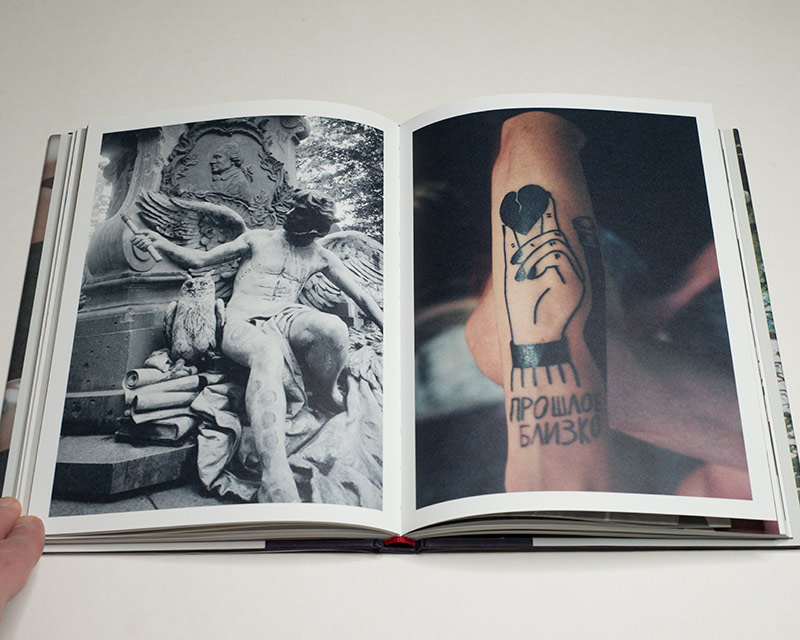

You will want to see УYY by Yelena Yemchuk in this context. The book was compiled from a number of previously separate projects by the artist, which include photography and painting. I think it is the intermixing of previously unrelated material that makes the book stand out. Of course, the work was related before in the sense that it was made by the same artist. But typically, separate projects are not intermingled the way it was done in and for this book.

The overall spirit of the book is one of playfulness, albeit an adult’s. Unlike children, adults know of the horrors of the world, and they can incorporate it into their playing, creating unsettling aspects.

I have no way of knowing how I would perceive the book if the war was not going on right now. On the one hand, the war adds a terrible sense of heaviness. I’m imaging the people in the pictures sitting in air-raid shelters, some might serve in the military, yet others might have found temporary homes abroad. I’d rather not imagine that some of them might have been died, say in an apartment building targeted by the war criminals in the Kremlin.

On the other hand, it’s exactly the war that amplifies the book’s overall feeling, namely that there is a rich culture, a culture beyond our simplistic Western understanding. The war lends an urgency to the book: “We are still here.”

Yemchuk’s parents emigrated when the artist was a child, meaning the book was made by someone who essentially re-discovered the country of her birth. While some people might use this fact to contest the importance of the book for Ukraine, I do think that such a discussion would be missing the real point of art. As I said, art is not defined by one truth, and it’s not clear that an insider’s view is automatically preferable over an outsider’s (or here, an outsider-insider’s).

Even as book making is incredibly difficult, given the fact that most photographers and many book makers are part of the precariat that the neoliberal world of photography has created, as a cultural artifact the book has enormous importance. УYY and earlier A Sensitive Education (find my review here) has me excited about seeing more from Départ Pour l’Image, the publisher behind these two books.

I personally am not necessarily very interested in finding the next publisher that will take over as that one hot photobook publisher. Instead, I’m more interested in the whole field expanding out steadily, with previously underrepresented regions filling in blanks in the world map of photobook publishing.

УYY; photography and paintings by Yelena Yemchuk; essay by Luca Reffo; 160 pages; Départ Pour l’Image; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!