“During my service for the Military Medical Museum of the Red Army, from November 1943 to May 1945” wrote Valery V. Faminsky in an autobiographical sketch, “I served on seven fronts in WWII. […] From the 22nd of April to the 24th of May 1945, I covered the Russian entry into the suburbs of Berlin and then inside the city.” Cue forward 70 years. Arthur Bondar: “In 2016 I saw an advertisement online that somebody was selling the negatives of a Soviet photographer from the WWII period. […] the seller […] briefly spoke of the photographer, Valery Faminsky. After his death […] relatives discovered this collection at Faminsky’s apartment. Nobody was interested in the photography, so the family decided to sell it.” These two texts can be found at the end of Berlin Mai 1945, a book that now presents the photographs Faminsky took during the final days of World War 2.

There’s something staggering about the history of the book itself. Without the history that can be found depicted in the photographs, its relevance would of course be vastly diminished. After all, photographers die all the time, and their archives are then being sold off online. These days, a book made about or from a find has become a regular occurrence in the world of photography. In fact, some artists and publishers have turned this approach into an industry of their own.

Still, the frequency with which pretty amazing material is being discovered for me points at the fact that the history of photography as written is at best the tip of a vast iceberg. What is known, in other words, or what is famous and/or celebrated often enough is not necessarily the best. It’s often known simply because it’s known and because something else has been suppressed or not discovered or dismissed. It’s very possible that some of the most amazing photographs ever taken will never see the light of day again (pardon the pun) simply for that reason — while the same old tiresome stuff is being peddled in museums all over the world.

What makes Faminsky’s photographs so interesting isn’t just that he happened to be in the right place at the right time. He was also an extremely skilled photographer who took pictures of a bewildering variety of scenes (I have seen other books of somewhat similar WW2 era material, and many of them fall short in that regard). For example, there’s a photograph of an almost a little bourgeois looking Soviet soldier who is depicted painting (in front of a shop named “Panther” whose shutters are drawn). A few pages before him, there’s another painter holding what might be a small watercolor (in the back of the book, he is identified as “Kitayko, a painter from the Grekov studio”; this is the second Grekov studio painter in the book).

There are ample photographs of an utterly devastated Berlin, there are what can only be called propaganda pictures (such as one of some meeting around a table in front of a tank — a good example of Socialist realism if there ever was one), there are more photojournalistic pictures of the military advancing and wounded soldiers retreating, there are what look like more casual snapshot portraits, etc. It’s a truly incredible archive that is now widely available again and that adds visuals to a widely known story.

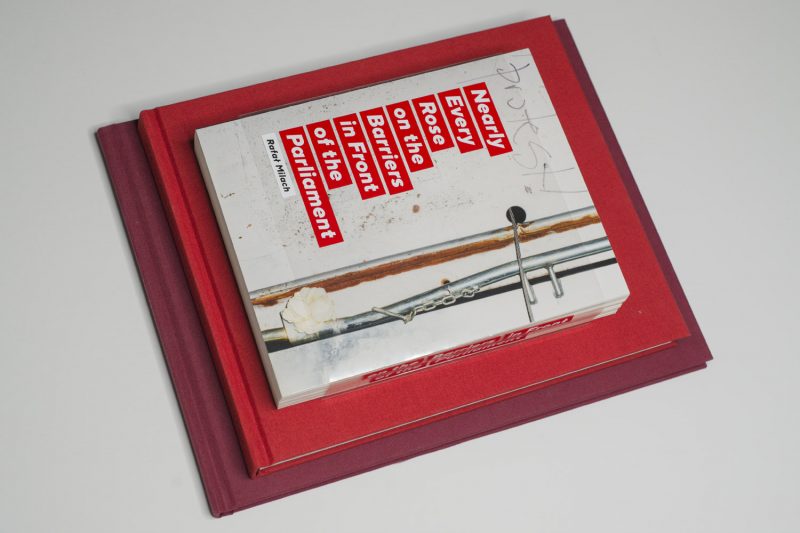

Berlin Mai 1945; photographs by Valery Faminsky; test by Arthur Bondar, Valery Faminsky, Peter Steinbach; 184 pages; Buchkunst Berlin; 2018

(not rated)

Almost three years ago, I wrote a short opinion piece entitled Why does it always have to be about something? It garnered some attention from photographers who don’t work with projects that are “about” this or that, who, in other words, make pictures, and that’s it. In principle, that approach should be fine — and it is, but it has become somewhat uncommon. These days, every photographer is “exploring” or “investigating” something, and s/he then produces a project about that something before moving on to some other something (or the same thing in some sort of variant).

I’ve even noticed that many young photographers I speak with get nervous when facing the prospect of making pictures without knowing what it’s all going to be about. It’s almost as if the thinking well known from the editorial part of photoland has taken hold everywhere: everything has to always be about something, and you work on everything in chunks that then — inevitably — become a narrative-driven photobook.

If you’re someone who doesn’t work with that approach, you might feel that you’re on your own, that you’re not en vogue (it escapes me personally what would be so terrible about that, but that might be my age or lack of or actually complete and utter disinterest in competitiveness showing). Another way to approach this situation might simply be to go about what you’re doing, and with an increasing archive of seemingly unrelated pictures at hand you’ll then pull out the strands that might show up after all.

I don’t want to make it sound as if that’s how Jem Southam‘s The Moth came about — I don’t know. The book’s afterword makes me think my hunch is correct, but since as a critic I question everything photographers say about their own work, I can’t go with that. What I can say, though, is that the book feels to me as if it were made this way, with the artist (who for me is one of the very finest contemporary landscape photographers there is) pulling a particular strand out of thirty years of work, to arrive at this very melancholic and introspective book.

Looking at the book had me think of being in the presence of the man behind the book, of sitting near him, watching him. Without a single word said there’d still be a lot communicated about a life lived, about what it means to be alive. I couldn’t necessarily say what it’s all about, but it certainly doesn’t matter at all. It’s beautiful.

The Moth; photographs and short text by Jem Southam; 72 pages; MACK; 2018

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.7

As Jason Stanley outlines in How Fascism Works, there is a neo-fascist assault on democratic institutions happening in many countries all over the world. In some countries, that assault has been hugely successful, turning previously democratic societies into shadows (if that) of their former selves; in others, the struggle over the future is still undecided. In some countries, its institutions that have led the resistance (for example in the US), in others, it has been the people themselves.

For a large variety of reasons (most of which are beyond the scope of this review), I have been watching events in Poland very intently. Faced with an onslaught of illiberal laws by the neofascist party in power (PiS), Poles have taken to the streets time and again to protest and make their voices heard. In light of the country’s recent history, with its Solidarnośč movement ousting the communist dictatorship imposed on the country after World War 2, this might not come as a surprise.

But still, I find the many expressions of civil resistance hugely inspiring, especially given how adept it has been at using very simple and effective visual symbols. For example, to fight PiS’ undermining of democratic institutions, the fact that the Polish word for constitution (konstytucja) contains the words for you (ty; strictly speaking this is the informal you, which makes this even more effective) and I (ja), a protest poster makes use of these details (see above), with the main word’s two constituent parts highlighted in the country’s national colours (white and red; see this article for details; this one has a lot of details and other posters).

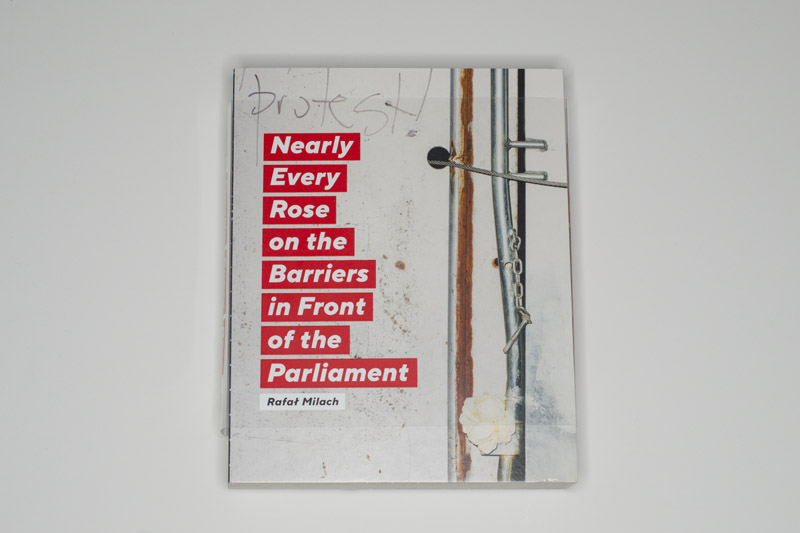

There have been other symbols as well, such as white candles and white roses. In a nutshell, Nearly Every Rose on the Barriers in Front of the Parliament by Rafał Milach is really “only” what its title says it is: a collection of such photographs, with the barriers providing the rough canvas against which the fragile flowers seem so powerless and powerful at the same time. It’s an accordion book that when unfolded present the viewer with a barrier of her or his own. On its back, there is a collection of anonymous uniformed men, made ever more ominous through the clever use of a heavy dot pattern.

In a variety of ways, the book is as inconsequential as photobooks are: they’re not going to change the world. But it’s an individuals gesture of resistance, which neatly ties in with his fellow citizens’. So I find the fact that a visual artist would actively engage with his country’s convulsions hugely inspiring (this isn’t Milach’s first project around the topic, and I suspect it will not be his last).

I wish I would see this more in other parts of the world. There simply is too much at stake for all of us. If photoland really cares as much about the state of the societies it operates in as it proclaims, then it would be awfully nice to see this expressed a bit more: where is all the protest art?

Nearly Every Rose on the Barriers in Front of the Parliament; photographs by Rafał Milach; accordion; Jednostka; 2018

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.0

Ratings explained here.