“At least 800,000 people have died due to direct war violence, including armed forces on all sides of the conflicts, contractors, civilians, journalists, and humanitarian workers. […] The cost of the Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Syria wars totals about $6.4 trillion.” writes the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University in the summary of its Costs of War Project. “This does not include future interest costs on borrowing for the wars, which will add an estimated $8 trillion in the next 40 years.”

There is no end in sight. This year, the United States will have been in a constant state of war for 20 years, with very little to show for it. But war for sure is a mighty drug. President Biden wasted little time after he sworn in, ordering his first air strike on 26 February, 2021. Meanwhile, a large number of those displaced by the wars have created the European migrant crisis.

I remember that at some stage I tried to understand the Thirty Years War. It was a real struggle, and to some extent, it still is. How could a war last 30 years and in many areas of the affected countries result in population losses of over 60%? Now, these numbers don’t seem so abstract any longer. After all, the United States has been at war for almost as long as I have lived here. In tandem, the militarization of its society has been ever increasing.

For a while, especially at the very beginning, things were pretty scary. I remember that when an acquaintance moved to California, he decided to drive cross country. For his trip, he got his car decked out in those yellow-ribbon “Support the troops” magnets, knowing he wouldn’t easily make it through the so-called heartland without those. Now, things feel a little different. But it’s not clear to me whether it’s because things have moved back a little bit or whether we’ve just got used to the jingoism.

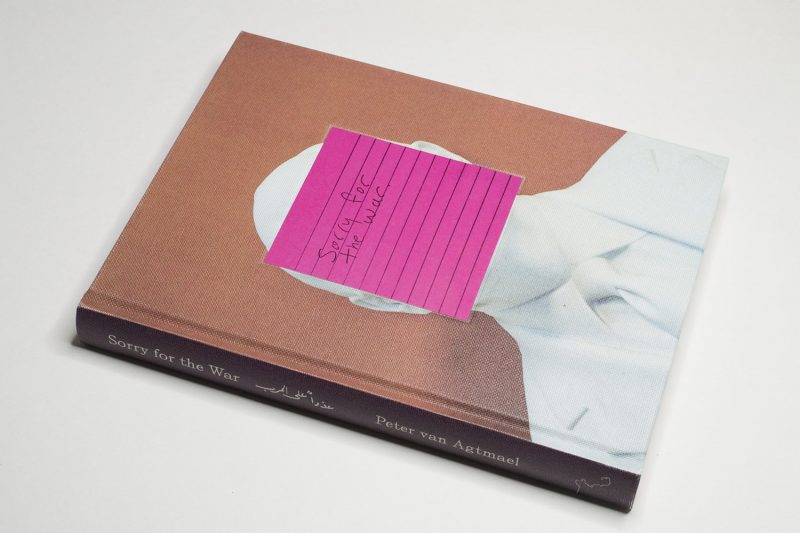

Peter van Agtmael has been documenting the Twenty Year War since its very beginning. I first spoke with him in 2007 and then again ten years later. He has published a number of books, all of them essential records of a country too embroiled in its own senseless militarism to recognise the folly of it all. There’s Disco Night Sept. 11, there is Buzzing at the Sill, and now there is Sorry for the War.

Rooted in traditional photojournalism, each of these books took the genre’s main conventions and tweaked them towards something that is a little bit less of the moment and more for that point in time where sudden enlightenment — to borrow a term from Zen Buddhism — might happen: what the fuck have we done?

Of course, we’re still waiting for our collective sudden enlightenment. Just look at this graph — that mountain range after the year 2000, that’s the Twenty Years War.

As its title indicates, Sorry for the War isn’t a book that sees sudden enlightenment happening any time soon. Instead, it observes how one insanity morphs into the next, as more and more lives are funnelled through the meat grinder that has been laying waste to larger parts of the Middle East and that has been mentally devastating those who volunteered or were forced to partake in it.

So the meat is ground and ground and ground, and Van Agtmael has the pictures that show some causes and effects and consequences. Just like in the Thirty Years War, it’s hard to keep up with what is cause and effect, and it’s hard to keep up with who is involved.

Slowly, yet steadily, the ripple effects of the war have been reaching further and further out, with, let’s say, Islamic terrorists spawned by a number of disastrous choices in Iraq killing Parisians, and the photographer happens to be right there, too (it was Paris Photo time).

At this stage, it would be tempting to write that the war essentially sustains itself. But such a statement would absolve those who have it in their power to stop it. There is a very telling photograph that shows mostly blue carpet and some wood-panelled long desk, with heavy leather chairs behind it — the US Senate, with its Armed Services Committee (support for the Twenty Years War might be the only bipartisan issue left).

Another photograph shows neo-fascist television personality Sean Hannity in what looks like a somewhat gaudily decorated Greek restaurant. There’s a man behind him, seemingly attempting to hold Hannity back by grabbing his right arm. But Hannity is having none of it. There is, after all, further meat to be ground, and it’s not the one in the restaurant’s kitchen.

Sorry for the War uses a number of video stills to point at the crucial role played by propaganda. These images include still from speeches by US presidents as much as from an ISIS video, Hollywood movies, anti-terrorism commercials, a Toby Keith video, or America’s Got Talent.

And there is one of Van Agtmael’s older pictures in a picture: a spread from a copy of Penthouse in 2009. The photographer is aware of his own role. He is not an outside observer (there are no outside observers: my own tax dollars fund the meat grinder, too).

The war might go on for another ten (or twenty) years — who knows? Looking at the book I came away with the feeling that the photographer knows that having chronicled things for so long now means that there will have to be something else — lest he becomes swallowed up by the meat grinder as well.

As photographers or writers we should all be so lucky: to have devoted so much time and energy on such an important topic, to have produced three incredible books that say so much, in such poignant fashions — as our country’s war rages on and on and on. Of course, it’s not luck that has been driving Peter van Agtmael. Instead, it’s his dogged devotion to the idea that the truth will win out in the end.

Highly recommended.

Sorry for the War; photographs and text by Peter van Agtmael; 200 pages; Mass Books; 2021

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.5 – Overall 4.0

Ratings explained here.