For better or worse, communities play a very important part of human life. Communities range from the most basic unit, the family, up to larger and larger numbers of people. Some communities are chosen — such as when someone decides to join a chess club, say; while others are mostly not.

For example, if, like me, you’re born in the relatively small town of Wilhelmshaven, Germany, then you are a Norddeutscher, someone who not only originates from northern Germany but who, at least that’s the idea, displays certain characteristics that people from there either claim to have or are said to have.

Therein lies the rub: often, community is a lot less well defined than those within it would like to imagine. Families have their black sheep, chess clubs tend to erupt in rather pointless infighting over the proper rules of engagement as a club, some North Germans are stoic and don’t talk very much while others will chew your ear of.

Community, in other words, tends to come with bad blood, and bad blood has the potential to create open conflicts, even (or maybe especially) when the underlying reasons have long been forgotten or were so minor that in retrospect the whole conflict seems positively ridiculous.

But we stick to communities because they’re not only the sources of conflict. They’re also the sources of deep meaning, regardless of whether that meaning is derived from abstract principles or from something very real.

The largest communities we know are conglomerates of states such as the European Union or the United Nations. Just below these conglomerates sit the smaller ones, states or countries, that often are less poorly defined than you might imagine. Or rather, they can be defined in any which way — whether originally from the outside or inside.

And therein lies the trouble, because not all peoples have their own sovereign entities — even if they want to. But also not all sovereign entities contain all the people that they think they should contain. Or, and this is where things can get particularly iffy, some people think they should have their sovereign entities while the rest of the country they belong to will deny their request.

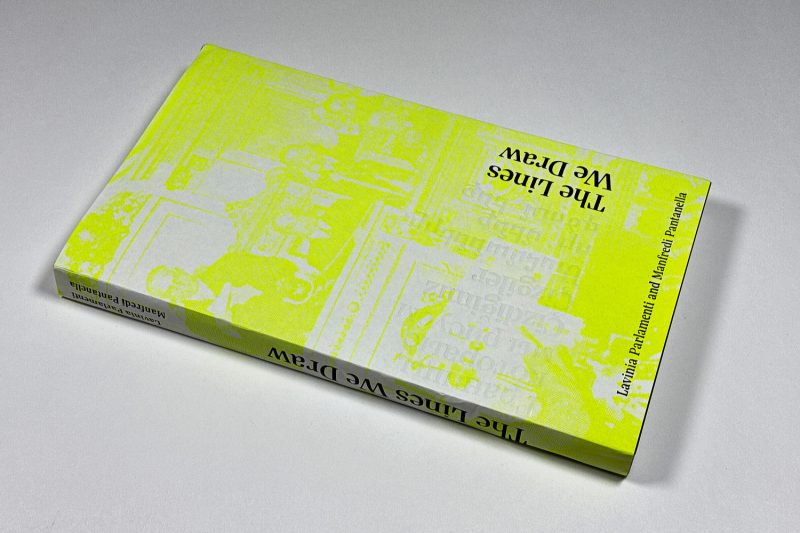

With their book The Lines We Draw, Lavinia Parlamenti and Manfredi Pantanella decided to focus on five different regions of the world that are not widely accepted as their own sovereign entities but that for some reason or another either exist as one or strive to do so. They are the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria), the Republic of Catalonia, the Republic of Artsakh, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR).

The duo traveled to these five locations to photograph there and to collect material for their book that is intended to look into what this might entail: being a sovereign entity. In principle, photography is not particularly well suited for such endeavours, but clearly the inclusion of a vast range of materials in the book is intended to help guide a viewer/reader towards some more clarity.

The subject matter with its various complexities (some of them being more real than others) presents a challenge for anyone trying to approach it in a photobook. I think the gold standard for such work is still set by the books produced by Rob Hornstra and Arnold van der Bruggen (The Socci Project) who managed to distill the many details they encountered in the Caucasus into a series of very clear and engaging books.

With their work, Parlamenti and Pantanella could have created a book with five separate chapters, each of which with a focus on one region. That probably would have been moderately interesting, but it would not have been able to get at the larger idea.

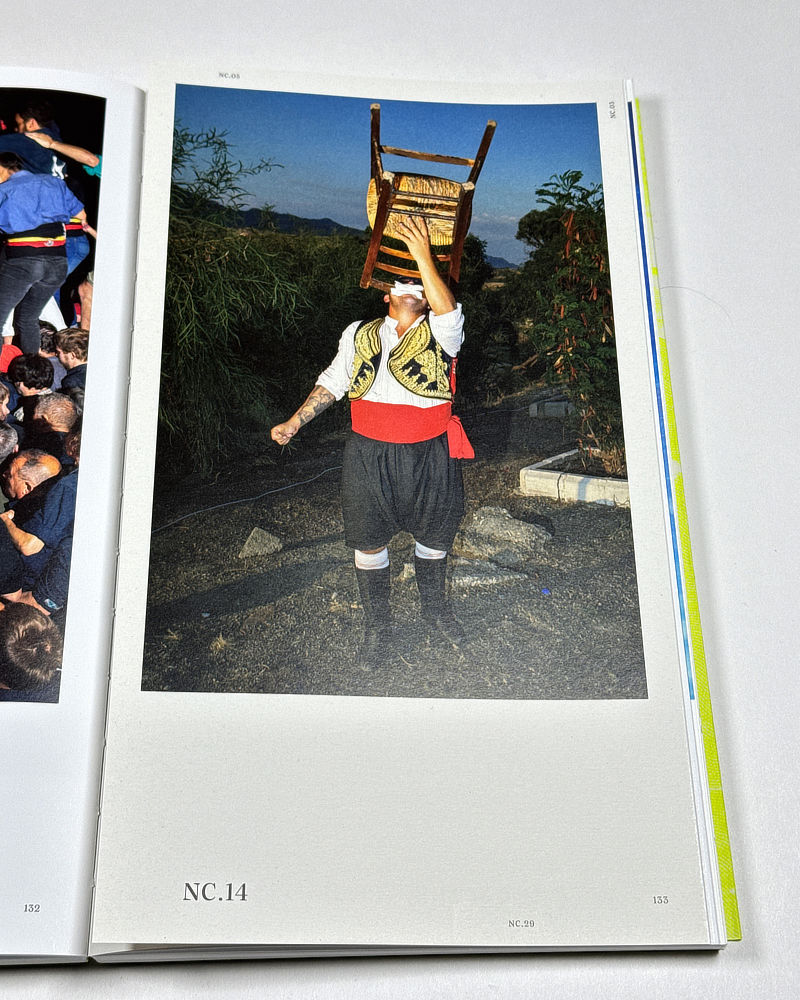

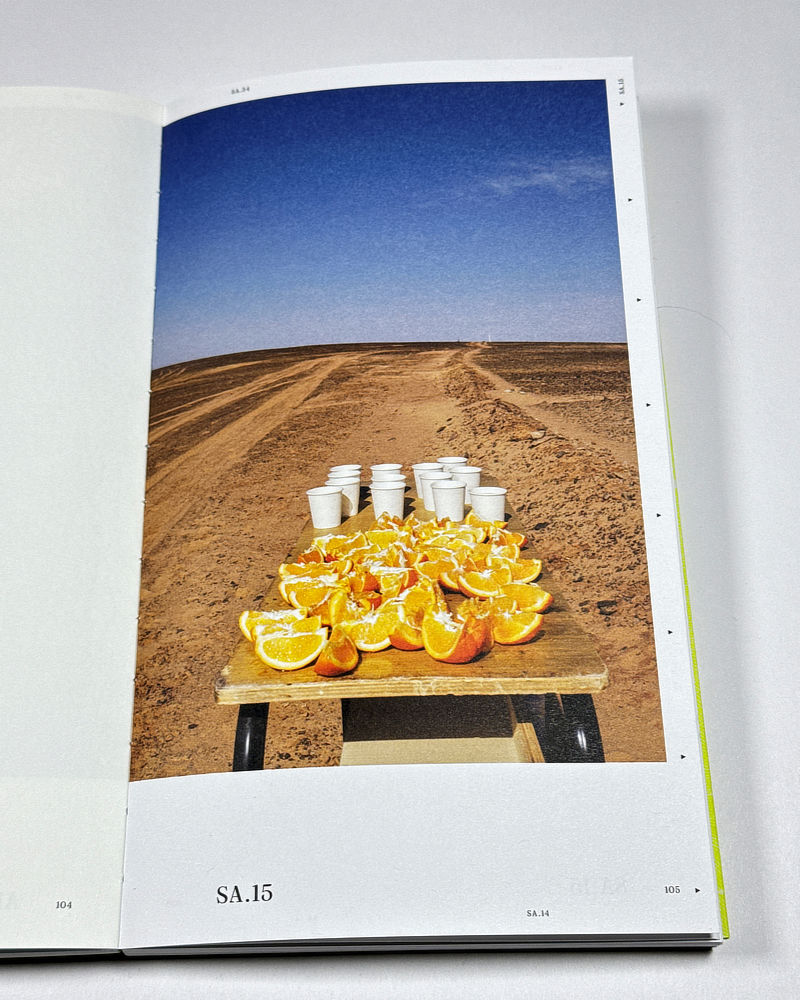

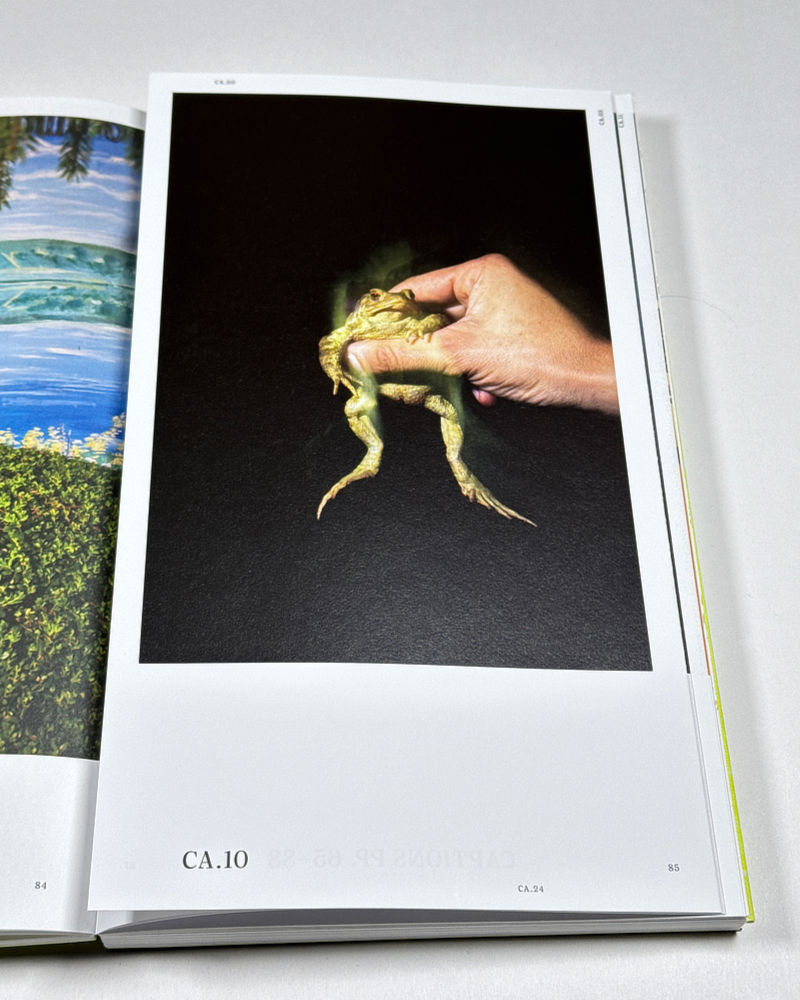

Instead, the duo opted for a book in which photographs and material from their various travels intermix. Visually, that was a very good idea. It is clear from the photographs that they were taken in different locales. Their juxtaposition opens up very intriguing relationships between seemingly disjointed parts.

This is where (or how) photography can be incredibly enlightening not despite of its shortcomings but because of it: you can make people see things that are difficult to describe.

Alas, the book utilizes an impossibly complex concept that creates a lot of confusion because it insists on the viewer being presented with a myriad of information at all times. In addition, images or text pieces are cut in half in numerous places, continuing elsewhere. At times, I even felt micromanaged, given how insistent the authors were that I would get exactly that one point they felt they needed to push.

It’s the kind of concept that violates the most important tenet of photobook making: keep it simple. Especially with complex topics, you don’t want to make a complex book because one (the complex book) does not help the other (the complex topic). And you want to leave some space for your audience’s imagination.

I tried looking at the various details in the book a number of times, only to get confused and bogged down in details that I did not think I needed to know. Ultimately, I realized that if I only looked at the photographs and ignored the rest, the book created a lot of interest in me.

In part, this is because the photography is mostly very, very good. More often than not the combination of the various photographs evokes a state of hallucination: what is real and what is not? Because, after all, is it not hallucination that sits at the core of so much of what is taken as the basis for a country?

Of course, that’s not how we tend to approach things in the real world (from which, it is important to note, these photographs were taken). Hallucinations aren’t real. But are the divisions in a chess club over some rules real? Are the differences between two people who happen to live on different parts of what might be an arbitrarily drawn line on a map real?

With so many conflicts and wars still erupting over those lines on the map (whether drawn previously or to be added later) — can’t we approach all of this as a huge hallucination and focus on what really matters? On being human beings living next to and with other human beings?

The Lines We Draw; photographs and text by Lavinia Parlamenti and Manfredi Pantanella; text by Hugo Meijer and Maja Spanu; 272 pages; self published; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!