It’s probably a fair statement to say that most Western societies have developed rather unhealthy ways of dealing with the most basic biological parts of our lives. People are born and die, and they are born after people have sex. Most aspects of this very basic and natural process remain hidden, usually either not to be talked about or when talked about then either in code (for example, “passing on” instead of “dying”) or in often grotesquely distorted ways (such as in the case of pornography). We are, after all, fascinated by all of that — despite (and in part because of) the vast set of stigmas and codes created around it.

As is always the case, the world of photography neatly reflects this situation. For example, a little while ago, the New York Times published a photograph of a Kenyan man who had been shot and killed in a terrorist attack. Other news outlets had published the picture as well, but with its own tone-deaf grandstanding, the Times asked for the response it received: “African victims of atrocities such as yesterday often get their death displayed for consumption with little to no regard for their privacy or the grief of their family members” James Siguru Wahutu was quoted in a BBC article about the incident.

Photographs of the dead, in other words, are firmly located in the world of taboos. How a newspaper deals with them exposes the concerns of the society it is embedded in. In the case of the New York Times, this includes both the taboo of publishing such pictures as well as denying other societies the same rights. What makes this Times case so instructive is not merely the implied neo-colonial attitude (which, granted, is problematic enough). It also points at a more basic fact concerning such photographs.

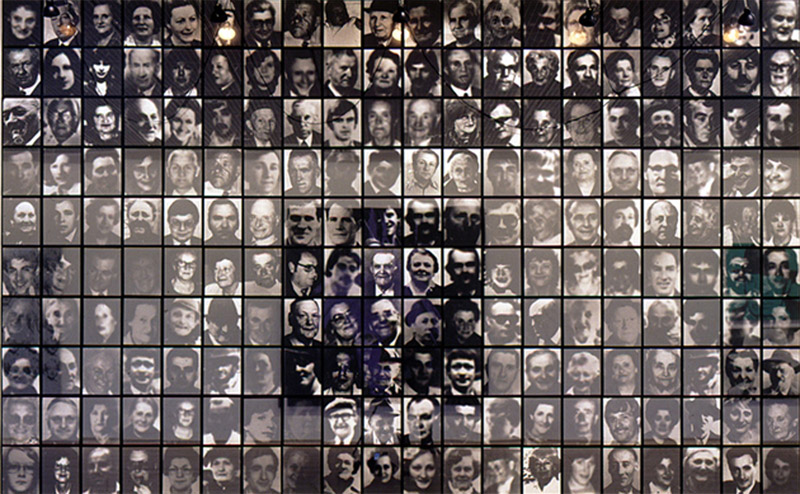

Photographs of the dead are deeply fascinating for people. But that fascination splits into two separate components for anyone who is intimately related to who is depicted and for everybody else (by intimately related I here mean either family members or close friends). A photograph of a dead person almost inevitably strikes terror in the heart of the beholder. If as a beholder you’re intimately related to the depicted there also is the vast loss experience and felt — feelings that are inaccessible for everybody else. It is this aspect of such photographs that Roland Barthes famously wrote about in Camera Lucida, starting out with a photograph of his dead mother.

An exhibition at C/O Berlin entitled Das Letzte Bild (The Last Image) — deftly curated by Felix Hoffmann — brings together a large variety of images to look deeply into how photography has been used to deal with death ever since the medium was invented (the exhibition is on view until 9 March 2019). Please note that for this article I’m working off the marvelous catalog published by Spector.

In fact, even if you can see the exhibition itself, you might want to spend time with the catalog. In addition to presenting the photographs, it features a plethora of insightful essays by a variety of authors about aspects of the exhibition, often centering on specific examples. What is more, I suspect that the experience of looking at the book will be vastly different. While this is usually the case for images on a wall versus on a page, here it is the very nature of the photographs in question that amplifies the difference.

During the 19th Century, a time when mortality rates were vastly higher than they are now, it was common to have a photographer take a final image of a deceased loved one (who more often than not might still be a young child). This practice might strike many people today as strange if not outright weird, but it is still being performed today (this — German language — article profiles a photographer who specializes in taking pictures of stillborn babies). I personally know photographers who took pictures of dead loved ones in funeral homes.

While death and the idea of the macabre are by construction related, they needn’t be addressing the same thing, or rather person. Death might be death, but the death of a loved one is always an entirely different entity to deal with than the death of a stranger. I suspect that if we were to ever be able to cross that divide as humans, things might take a turn for the vastly better on this planet (don’t hold your breath, though).

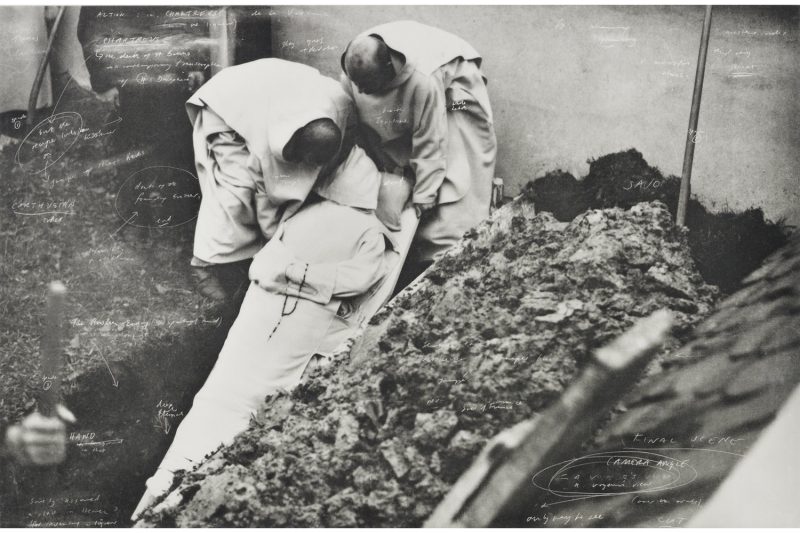

As The Last Image shows there exists a depressing archive of photographs made at the occasion of death meted out at people, whether during times of war or otherwise. While I find it hard to comprehend how someone could become a killer, I know that if the history of humanity teaches us anything, it’s that pretty much anyone can become one. But the ease with which people not only can become killers or active or passive bystanders for me isn’t remotely as disturbing as people’s documented willingness to have visual records, in which they are willing if not eager to appear, either as killers or as bystanders.

It’s not quite the same thing, but seeing the lynching photographs in The Last Image is as deeply unsettling to me as is coming across a well respected photojournalist posting a photograph of a dead person’s face on Instagram to essentially brag about his bravado (no need to point this particular case out — at the time of this writing, it’s from a week ago). Maybe these kinds of photographs need to be taken, and maybe they need to be shown in newspapers (these two aspects are deserving of further discussions). But for sure they should not be presented in pretty much the same way as those of hunters posing with dead animals (as always, your mileage might vary).

Unlike Barthes in Camera Lucida, when I look at photographs of dead people my focus become the dead and those responsible for their death, whether actively or passively. Of course, death might be caused by old age, illness, or some misfortune. But often enough, death arrives in the form of a human hand pressing some form of trigger. State-sanctioned killing disturbs me as much as outright murder, regardless of whether the sanctioning happens beforehand (war time) or after the fact (such as when someone who killed in obviously cold blood is acquitted in the courts).

Photographs might be viewed as documents, but they always are a lot more. As I wrote a few years ago, the act of photographing is an affirmation of one’s presence. But in many cases of death, it can also become an act of acquiescence, if not an act of open support (such as in the case of lynching photographs).

So photographs of death are as much about the dead as they are about those who are not — those who might be responsible for a death, those who might be bystanders, those who have lost a loved one… (or any combination of these). And, of course, much like all photographs they’re also about and for those looking at the pictures, the people who will respond to someone having pointed her or his camera at the dead.

More than anything, The Last Image can — maybe should — make us more aware of our own involvement, which ultimately also ties in with the fact that a stranger’s death is never the same for us as a loved one’s. Photography has a strange power of externalizing its viewers’ involvement (much like how in the world of business costs can be externalized and thus made to essentially disappear beyond the horizon). This is what makes it so easy to write tone-deaf and self-aggrandizing justifications for making or showing pictures of carnage for or in a newspaper, or it explains why after seeing all these photographs of death and destruction there still is no end in sight.

This is not to say that at any point in time photographs will have the power to change the world. If anything, they might change us viewers, and it’s then up to us to change the world. To change the world, we will have to recognize what is at stake for all of us, a task that is simultaneously made easier and harder by photography. Photographs might show us death, yet as I already noted they allow us to externalize possible reasons even further (which might include our own involvement, however indirect it might be).

So The Last Image ought to make us look not only at the dead and at all of the horror responsible for such vast parts of it, it also ought to make us look at how photography has the power to point out our own being connected to what is on display. At the very least, one fact is certain: one day, we’re all going to die. Maybe that’s why there’s a reflective band of material inserted into the black cloth of the catalog: the first things we’ll see are our own faces.