I just finished Adam Begley‘s The Great Nadar: The Man Behind the Camera. I can’t remember the last time when reading a photographer’s biography was so much fun. Even when well written, such biographies tend to be rather dry affairs, because the flamboyant, the irrational, the people who just refuse to grow up tend to prefer activities other than taking people’s pictures. As originally did Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, who first set out to become a writer, then became a rather accomplished caricaturist, then opened a photography studio, then got obsessed with ballooning… Or maybe it was ballooning first and then photography — such details would not have mattered much, if at all, to a man who seemed to have been possessed with an overabundance of ideas and energy, a true human dynamo, an Energizer Bunny before there existed such a thing (actually, batteries existed, but they weren’t very good — you’ll find out about that in the book, too).

I find it very hard to relate to people who lived in times so different than our own. I’m intensely fascinated by some historical figures. But there’s always this abyss of time, this abyss of everything I am taking for granted in all likelihood being somewhat or completely different many years ago. What had me enjoy this biography so much was the fact that this unknowable stranger, who happened to take some of the most amazing portraits in the history of photography, had such an insatiable appetite to realize ideas that even at the time must have sounded outright crazy to many people. Nadar, as Tournachon ended up calling himself (how and why the book explains), reminded me of the kinds of characters you can find in Tom Waits’ lyrics. However, while Waits’ characters mostly end up being somewhat tragic losers, Nadar showed that it doesn’t hurt to be crazy, as long as you make what seems crazy a reality. Goal post shifted: who says this can’t be done? Who says this is nuts?

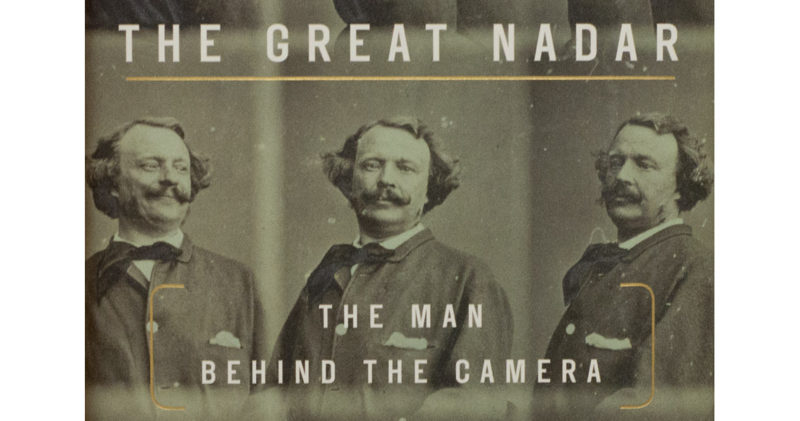

Seen this way, the photographs on the cover of The Great Nadar are a truly brilliant choice. Here are nine self portraits of the man (the original set has 12, you can see the remaining three on the back, albeit cut off), taken from different angles, as if he sat in a rotating chair, with Eadweard Muybridge operating the camera, except that Muybridge’s serial photographs came later (btw, Rebecca Solnit’s River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West is a great read, too, even though Muybridge’s life was mostly a lot less entertaining). But there’s one other crucial difference, because in one of the frames, you can see Nadar smiling (you can see it in the top image). I just want to believe that he was just trying very hard not to laugh. What a completely silly idea to take these portraits in rotation! What purpose would this serve in 1865 (or so), just a little over 25 years after photography had been introduced to the public? Well, obviously, Nadar’s: simply doing it for the fun of it, to see what the outcome might look like. That one frame gives it away: the fun of it. I’ve looked at these pictures so many times now, and it still gives me so much pleasure seeing this man enjoying himself.

Maybe Nadar was helped by the fact that there was no photographic tradition. There was a very, very short history, vast parts of it French. But if you were interested in photography in the mid to late 1800s the world was your oyster. I have a hard time believing someone like Nadar would have viewed the presence of a longer tradition as an impediment. He simply was too focused on his ideas to let others get in the way. This was, after all, a man who built a gigantic balloon to raise money for his pet aviation projects (which involved impractical helicopter models), a balloon carrying a two-story wicker house that, we are told, came with a wine cellar (of course!).

The world doesn’t feel like anyone’s photographic oyster any longer (or any kind of oyster really, unless you’re a member of the 1%). Reading The Great Nadar reminded me of that. It also reminded me of the fact that large parts of photoland seem to be so devoid of simple, silly fun, of laughter, of taking yourself not too seriously. In a sense, photoland has a lot in common with rock ‘n’ roll: most of its biggest stars, however accomplished they are as artists, aren’t necessarily well known for being lighthearted and funny. There is a seriousness (and usually literalness) to photography that often makes me feel like I desperately need to look at something else (ask yourself: how many truly funny photography projects can you think of?).

If I have one complaint about The Great Nadar it’s that it was over too soon. I would have enjoyed reading about Nadar for another 100, 200 pages. Many of his acquaintances and friends, people he photographed, were some of the most well known writers, composers, artists of his time. I would have enjoyed reading more about them and their relationships. That said, thankfully, the book never makes this celebrity aspect its sole focal point (it would have been so tempting to do so).

One thing Begley makes clear is that for all the fun and silly exuberance Nadar was considerably more than just a man with too many ideas. He was a human being like the rest of us, just a little more gifted, and just as flawed as we all are. I don’t know if I would sue my brother over a trademark I established (I have a brother but no trademark). I also don’t know if I would shelter the equivalent of a political refugee from certain death and then risk my life going to the authorities, telling them to pardon him. I would like to think I wouldn’t (sue), and I would (shelter), but I have no way of knowing.

Biographies can be great ways of learning about the choices other people made and of everything that resulted from those. Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, the man known as Nadar, had too many ideas and too much energy, so he just decided to realize as many of them as possible. In a world where there are so many options now, where we individually are given so many choices, having to fend for ourselves, someone like Nadar might come as an interesting role model: if you think you need to build that gigantic balloon to fund your helicopter research you might as well do it.

Life’s too short to waste any time, and there are too many other, equally interesting ideas just around the corner. If you want, you can be a writer, caricaturist, photographer, balloonist, and family man at the same time. And you can have a lot of fun while doing all of that.