Between 1897 and 1903, James Reuel Smith traversed Manhattan and the Bronx to documents its disappearing springs and wells. His documentation included taking photographs and ample notes, the latter of which often extended beyond mere descriptions of the sources of water. For example, part of an entry from 16 October 1897 reads: “This spring is some four hundred feet south of the slate-colored building that the Volunteer Army maintains as a home for discharged convicts until suitable employment can be obtained for them. There are now thirty of these men in the home, which is rented from Mr. Shay.”

A little over a century later, Stanley Greenberg followed in Smith’s footsteps to photograph the locations he had detailed. Now, with the exception of Central Park and a few other locations, all of Manhattan and the Bronx is covered with concrete, asphalt, and houses, leaving very little if anything of the land’s original state. Unlike Smith Greenberg didn’t take any notes.

It’s tempting to look at Smith’s photographs as reminders of what was, of what, in other words, has been covered up with layers and layers of materials. This approach would make for a grim exercise, given how transparently unattractive Manhattan’s and the Bronx’s lived environment actually is (as documented by Greenberg in his photographs). Of course, one could say the same about any modern city that has grown rapidly over the course of a single century (a little while ago, I watched a documentary about all the now hidden rivers underneath contemporary Tokyo).

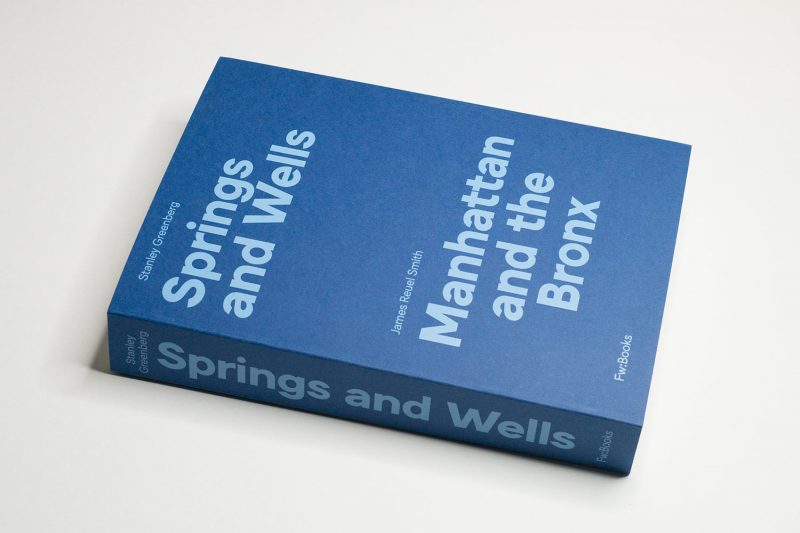

After all, the changes in these 100 years are too vast to allow for the kind of comparisons that can be made when locations are re-photographed that retain enough elements to show a world in flux. Here, in Manhattan and the Bronx, the flux has been too fast — the points in time are spaced too far apart. If someone were to look at the book that has now resulted from Greenberg’s endeavour — it’s entitled Springs and Wells (yet again, a very handsome production by FW:Books), they might be tempted to conclude that two completely different locations are being described (which, in a sense, is true, albeit not in a geographical one).

For me, it is Smith’s texts that offer most insight (if that’s even the right word). More often than not, there will be a number of details in them that open up a glimpse of a different time as much as an openness to observe beyond the purely geographic task at hand. The taste of water at a number of springs and wells is described. You’d imagine that in such a small area there would not be any variations but you’re mistaken. Also: yes, water has a taste (of sorts).

Furthermore, there are all those little idiosyncrasies of life that Smith manages to sneak into his text. Names are given even as the people behind them don’t play a role: for example, there’s the Mr. Shay who has rented out his property. All of these descriptions go beyond the photographic, and they hint at photography being seen differently (if not used differently) at the time when Smith compiled his collections of springs and wells. I’m thinking that he bemoaned not only the disappearance of these sources of water but also the increasing inability of those around him to see more of the world than an area to build on.

But there is another aspect of the book, something that I have been thinking about on and off. Photography appears to be particularly attractive for obsessive people, doesn’t it? There’s something about a camera that invites its users to produce not merely a sampling of something. No, it has to be a complete, exhaustive (-ing) collection of material: things, locations, people — whether it’s water towers or gas tanks or other industrial buildings, the German people, gas stations, springs and wells in Manhattan and the Bronx…

What is it with us photo people being these kinds of creatures?

I’m obviously unable to approach this particular subject matter as an outsider. I not only take my own pictures, I also observe other people’s picture making (and the books and exhibitions that result from them) from the inside, from that place known as photoland. Consequently, I don’t know what this might look like from the outside.

I have not compiled evidence that would hold up to scientific scrutiny. So far, conversations with non-photolandians tend to support my observation. In fact, those outside of our own niche seem to view what I outlined with even more suspicion that I do. We are obsessive people, out to collect our visual treasures in such a way that no detail or no example may be omitted — often at the expense of exactly the lightness of touch that makes so much art art.

Maybe this is what had me connect so much with Smith’s texts and those seemingly irrelevant observations around the springs and wells. Strictly speaking, they’re not relevant — why would have to know the name of a man who rents out some property that’s near a well? But what if the name is the actual point — and not so much the water itself?

I’m not sure, yet, where this would leave me. For sure, it would create an opening in the book that would ask me as a viewer and reader to become mindful of all the things that are excluded when something is done in just an exhaustive photographic fashion.

It seems obvious that this particular consideration is besides the point here. Springs and Wells wasn’t made to have people think about the role of photography. To make this clear, I do not intend my considerations as a criticism of the book. Instead, I want to speak of the opportunity provided by any piece of art, namely that it can trigger a discussion that’s expressly outside of its own bounds.

That, after all, is something else that I see as connected with the obsessiveness and quest for completeness that we witness in photoland so often: I perceive a lack of flexibility, an inability or unwillingness to allow for a discussion to go sideways (I wouldn’t want to necessarily imply a moral statement out of this, so feel free to pick whether you see this as an inability or unwillingness), to dig up Mr. Shay and give him a small and completely irrelevant part of the story.

Maybe we can all learn a thing or two from James Reuel Smith and look out for the Mr. Shays — or someone else, regardless of who he or she or they might do.

Springs and Wells, Manhattan and the Bronx; photographs by James Reuel Smith and Stanley Greenberg; text by James Reuel Smith; 496 pages; FW:Books; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.