Please note: The author generated this text with the help of GPT-3, OpenAI’s large-scale language-generation model. Please refer to the notes at the end for more details.

The surfaces of any modern city are a hodge podge of mass-produced materials, set against each other without regard for what sits next to what else. This is done this because it’s cheap. The problem is that it doesn’t look good. People don’t know what to make of it. This is why everything has to be branded. In the same way that the modernists thought that a city could be designed by a vision, the thinking now is that a city can be branded. The idea is to create a city that looks like a designed object, but it’s done in a way that’s controlled by the marketplace. New buildings are a lot like new cities: they look good, but they don’t feel good, resulting in a city that looks good, but feels bad.

The modern city is thus defined by its surfaces, by the accumulation of materials on top of them, and by their erosion. These traces of human activities are ubiquitous, and they are familiar. They are thus easy to miss, easy to overlook. But they are not invisible. They can be analyzed, studied, recorded, and, through the reproduction of their forms, re-imagined.

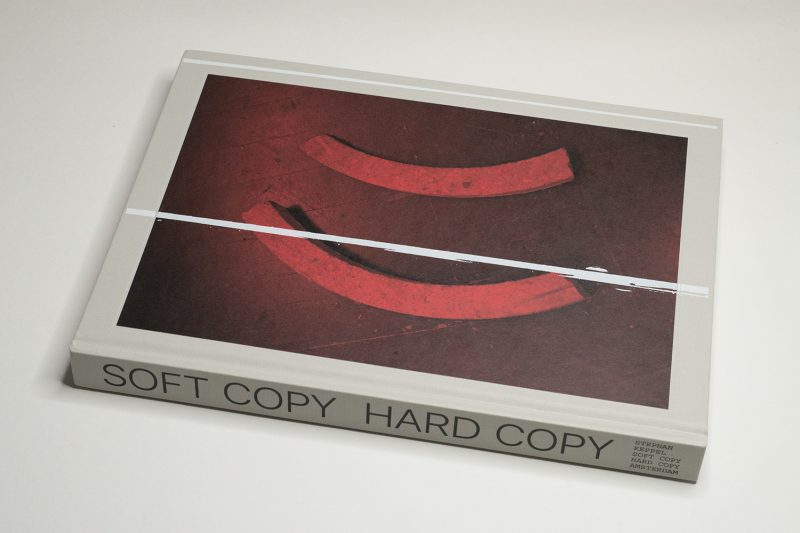

To describe Stephan Keppel‘s Soft Copy Hard Copy as a re-imagination of Amsterdam is apt. There is very little in the book that will remind a viewer who is familiar with the city of what she or he might remember. There is no great canal, no Anne Frank House, no zoo, not even a canal ring. A book is a fantasy, it can be whatever an artist wants it to be. And Keppel’s Amsterdam is a city of the 1960s, with a touch of the 1970s. It’s all surfaces and materials. It’s a city that looks like it’s made of cheap plastic, cheap wood, cheap stones, all of them grimy.

The images depict a built environment made out of materials, components, platforms, and other things that can be found in a hardware store or on the street. Keppel’s book uses photos of buildings as a vehicle to talk about the city and culture that produced them. Soft Copy Hard Copy is about the creation of buildings, their architecture, and construction. It is about neglect, in particular the kind we don’t think of as such: opting for cheap materials, for layering of materials upon materials, for doing the job and just the job.

After all, the marketplace’s cheapness of the materials has resulted in a cheapness of our own ambitions on the job. This is unfortunate, because the motivation for the cheapness of the materials is the perception that quality isn’t worth it. Ultimately, though, the marketplace is just responding to our demands. So why don’t we demand better materials? It’s because we’re under pressure to be cheap. But this causes a big problem. Cheap building materials don’t last. So they’ll need a lot of maintenance before long. And then they’ll need even more maintenance after that. And so on and so on and so on. It thus becomes a feedback loop of cheapness, cheapness on top of other cheapness. It’s a downward spiral, and it’s why buildings today are increasingly more expensive to maintain.

For an artist, the cheapness becomes a fodder, though. Keppel photographed and accumulated the materials, extracting forms and shapes. One might imagine him expressing his ideas as follows: “I think in all my work, the collage is very important. I like to play with different materials, different shapes and forms. It’s about the materiality of things, that you can create something new with old things. And I like that.” (This sentence isn’t an actual quote by the artist; it’s something the AI created. Given the experimental nature of this article, I decided to keep it, while being transparent about how it arose. — JMC)

Furthermore, depictions of materials and patterns become their own materials, as Keppel scans and photographs instruction manuals, books that showcase samples of materials, and his own photographs of surfaces. Much like in his book about New York City, the result has very little to do with the Amsterdam a visitor or even a local might notice. An index at the end reveals the sources of what to a viewer might come across as a random selection of forms and surfaces.

This is a book the viewer needs to let wash over themselves in order to fully appreciate. It’s a book that rewards patience. It’s a book that will make the viewer want to re-examine the places walked past and the things passed by on a daily basis. It’s a book that will get them thinking about the things they see every day. The book could be described as an “exquisite corpse,” a book in which each page is assembled from images contributed by various artists who are given only a few guidelines and no instruction — except that all of those artists hadn’t been told where and how their “work” would be used.

It’s also a book that is likely to confuse many viewers, leading them to ask themselves “why am I looking at this?” And, yes, what is there to see in these grimy surfaces and materials? Sure, we can see things like the marks left by the someone’s hand, but is this really that interesting? From the perspective of an art critic, the answer is yes. But from the perspective of a lay viewer or someone casually interested in photography, it’s not clear. What seems clear is that many people are going to find the experience of looking at these photographs to be a very unpleasant one. And this might be the key to the experience. The images often are visually unpleasant. They’re full of dirt and grime, of neglect and cheapness: the dirt and grime, the neglect and cheapness of our lived environments.

In part, this work is critical in its attempt to challenge our expectations for how photographs are supposed to look, and it challenges us to look at our world in a different way. But at the same time, there’s not much here that’s political, or even all that provocative. Indeed, this work seems almost apolitical in its refusal to engage with its viewers. And yet if this work isn’t political, that doesn’t necessarily mean that it isn’t political. As noted above, one of the central elements of this work is its desire to frustrate and put off its viewers. And this can be seen as political (or at least anti-political) in that it refuses to pander to its audience. It refuses to provide them with easy answers or eye candy. Instead, it provides us with something much more difficult: a deeply frustrating experience that may well leave us feeling like we’ve wasted our time by looking at it.

If we indeed have wasted our time looking at these pictures (which, to make this clear, I don’t think we have), then that means we’re wasting our time looking at our lived environments. Where does this leave us? It is exactly that question that I believe Keppel wants us to deal with. There are no easy answers, but that is the point of the book. If we’re going to be living in these environments, then there needs to be some understanding of what they are. Whether that understanding comes from the designers, the builders, the artists, or the critics is another question. But to not have that question being asked is the problem in the first place. To not have that question being asked is to be ceding the ground to those who will ignore or abuse it.

To finish, I think it’s important to note why I care about this book. I’m a critic and a writer. I care about how people live and how they think about how they live. I’ve been a critic for so long that I’ve had to learn how to be a critic of myself. I care about these things so much that I do them for free. I care about these things so much that I’ve written a book on them and am currently working on another. I care about these things so much that I’ve failed a lot and suffered a lot of rejection as a result. I care about these things so much that even if none of it ever pays off professionally, I’ll keep doing it because it’s important to me and my family and my friends and my colleagues. In short, this book has made me better at what I do and it will continue to do so until it becomes irrelevant or until I’m dead.

Soft Copy Hard Copy; photographs and images by Stephan Keppel; 240 pages with poster; FW:Books; 2021

Production notes: As described in the very beginning, this article was generated in part with GPT-3, OpenAI’s large-scale language-generation model (using the “Da Vinci” engine). “Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3),” notes Wikipedia, “is an autoregressive language model that uses deep learning to produce human-like text.” In a nutshell, the algorithm gets trained with existing text (written by humans), and it then learns how such text operates, to be able to generate it on its own.

Given that GPT-3 essentially creates “copies” (however loose they are) of other materials, I thought it would be perfect for this particular book. That said, as a reader, you will want to keep the experimental nature of this article in mind.

GPT-3 operates on the basis of prompts. You supply it with (a) sentence(s) (or even just a word, which I didn’t do). And it will then generate text based on that (those) sentence(s). For the most part, I did this in an iterative manner. I would first write a sentence and let the machine generate text. My sole criterion for whether to accept or reject the result was based on whether it made sense in the context of the book. For example, whenever the AI started writing about something very different, that text was rejected (at times, the AI would produce what essentially looked like parts of standard press releases by gallerists or museums).

Once there was text that made sense as a continuation of my prompt, I would edit the text to make its style and voice fit my own, cutting out smaller parts that wouldn’t fit (or that were simply repetitive or superfluous), and at times adding little bits. Depending on how much text I ended up with, I would use the longer text as a prompt in its own right and look for further output. In general, a paragraph or a couple of paragraphs are the typical outcome of any such iteration. The AI would move too far from the book/topic afterwards. I those cases, I started a new paragraph with a new prompt.

I rejected all text that I felt would do a disservice to the discussion of the book or artist in question. Even though the AI attempted to insert first-person narration throughout, I removed all such parts (in part because their logic didn’t make any sense), with one exception that is very easy to spot.

In the end, this article effectively is a montage of iteratively constructed parts of AI-generated text, each one of which was initially prompted by me.

Before I started, I made the decision not to mark which parts of the text were written by me and which parts were generated by the AI. The idea of my editing was solely to make the text legible and not confusing (avoiding abrupt changes in narration, where such changes would simply be confusing). In the final text, about 75% of the text are text produced by GPT-3.

The generation of this article resulted in costs of $0.70 (for the use of the AI engine).

I’m deeply indebted to Nelis Franken for introducing me to GPT-3 and for his many attempts to make me understand the logic behind it. All inaccuracies in terms of the descriptions above are solely caused by the limitations of my own understanding of the machine.