The standard process for making a photobook goes something like this. You take your thousands or hundreds of photographs, and you whittle them down to the few dozen strongest ones, which you then proceed to put into an order based on the idea of the work. This method is well tested, and it works well with 99% of all photography. The reason for that is that in the world of photography, the main (mostly unspoken) idea is that photographs are special entities.

If you go to art school, say, to get your very expensive MFA, that’s what you’re being taught: focus on the single picture and try to make it as brilliant as you can. As I outlined earlier, this model is based on the idea that photography is an art form. Thus, it better conform to that world’s conventions. To a large extent, the art world has let itself be defined through commerce. And art dealers prefer unique, expensively made things because that’s what rich people like to possess.

But as Lewis Bush pointed out, photography is too interesting to be treated as art. Even if you still think of yourself as an artist, you might want to consider what this means. It might have consequences for how you see photographs — especially your own. A few years ago, I wrote about what this could mean. In hindsight, I feel that the article doesn’t quite convey the importance of what it tries to get at. (I tend to have this problem with my articles. It tells me that I’m still learning: moving my own goal posts. I’ll stop writing once I find that I’ve stopped learning.)

If you ditch what I called the precious-picture problem, you’re in a different world. To begin with, you’ll have to re-consider how you make your pictures and work with them. How do you edit work when you’re not merely picking the “strongest” pictures (whatever this might even mean)? And what exactly does the work communicate? What could a book look like?

An absolutely brilliant example of such an approach is provided by Anders Edström‘s Shiotani. As an object, the book is modestly sized and relatively hefty. Once you start looking at the book, you realize where that heft is coming from: there are hundreds of pages printed on a rather thin paper stock. But the book’s real heft is what it is doing. I’d find it hard to attribute regular photobook terms to it because if you’re looking for anything that’s common in other photobooks, it’s completely absent here.

From what I know, every form of art has its outlier creators that push the boundaries of their chosen medium by essentially exploding them. If you approach their work expecting to be faced with what you’re familiar with, you’ll inevitably be disappointed. And it’s likely that you will also find yourself bored because you’re not being given your regular kick, while the work demands to be seen on its own terms.

For example, if you watch Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker expecting a movie that follows Hollywood standards, you’ll be in for a huge disappointment. Somehow, nothing appears to be happening. Or rather, there are a few things that are happening. But you could essentially condense that action into five to ten minutes of movie. In much the same fashion, if you listen to a classical symphony expecting it to use the conventions of pop music, you’ll also be bored out of your mind. However, if you listen to a piece of free jazz or psychedelic black metal you’ll be just aghast: how the hell is this music? Where is the structure you’re so used to?

All of these examples have in common that they unfold on different time scales and, crucially, that they need to be experienced on their own terms. This very much holds for Shiotani as well. How do you look at a photobook with hundreds of pictures, in which seemingly nothing is happening at all? Well, you just do. You allow yourself to give in to it, because the rewards are incredible.

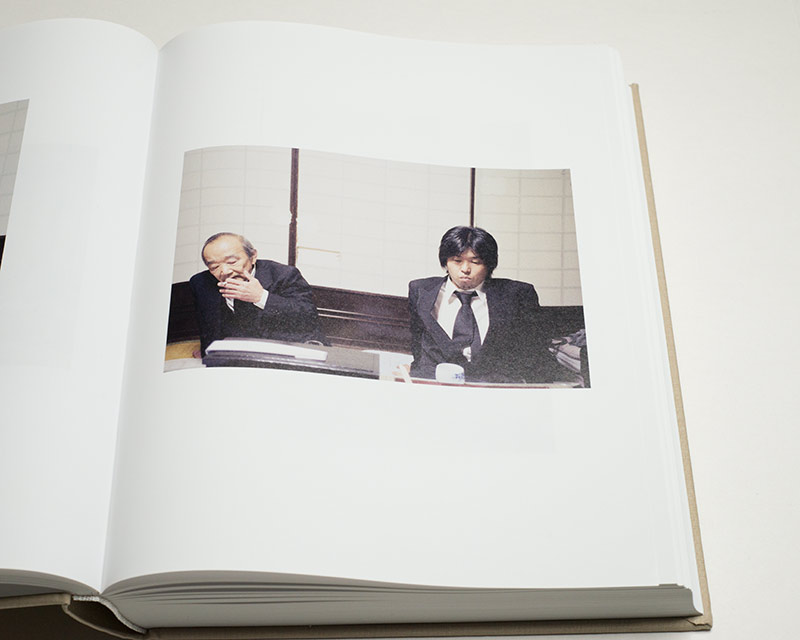

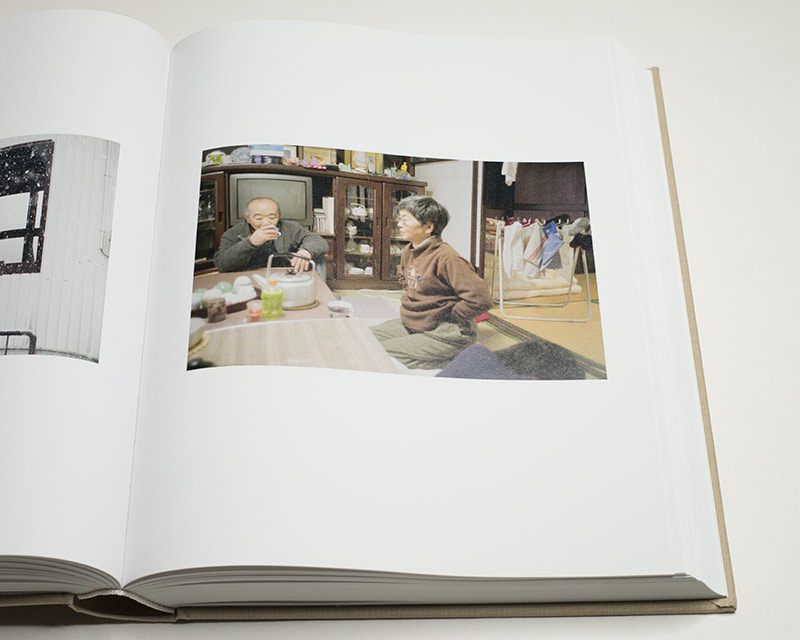

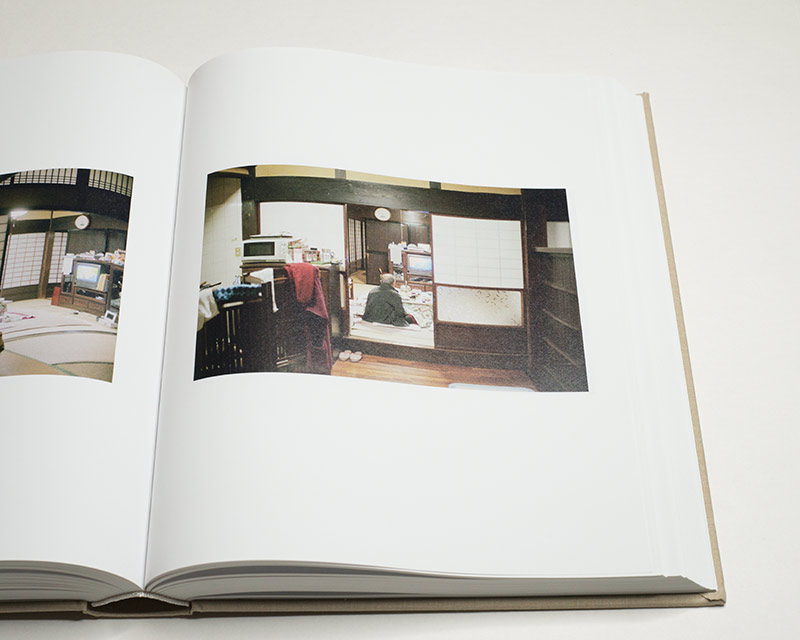

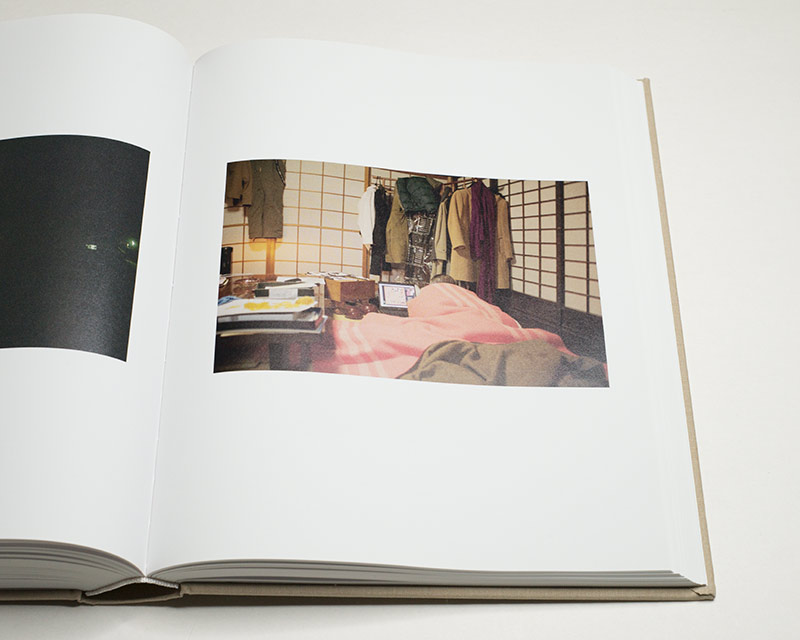

What exactly do you encounter in the book? There is a relatively small group of people, many of them elderly, that live in what looks like a traditional Japanese house somewhere in an impossibly nondescript countryside. The location lacks any of the visual attractions that you might think of in the case of Japan. The hills look perfectly pleasant. But there are no torii gates, elaborate rock gardens, or bamboo forests. If they exist somewhere nearby, they are not shown.

Shiotani, Google Maps tells me, is a hamlet to the northwest of Kyoto. On my smartphone, it is a red marker surrounded by green. When I zoom in, the marker remains even as the rest of the map starts to fill in with details. At the smallest level, it turns into a red outline around its name, with some Ono Dam slightly to the south and a Mt. Chorogatake to the north north east. Is this the correct Shiotani? A few Google Street view pictures have me convinced that indeed it is.

My guess is that almost all photographers I know would have a hard time taking a single picture in that location. It would seem that there is nothing to take a picture of. But where are all the pictures in the book coming from? That’s where it gets interesting. In a nutshell, with very few exceptions, none of the pictures shows a moment that’s worthwhile remembering. That is the book’s brilliance.

As you start moving through the book, you’ll slowly get rid of expectations of something happening, to instead become immersed in a world that cherishes its quiet moments, its being very mundane. This is, in other words, our own world — the one we too often try to get distracted from by looking at precious pictures or whatever else. Nothing is happening: there is a meal, and then there is another meal, someone gets up to exit the room, the seasons change, and every once in a while someone dies.

There’s a movie that’s connected to the book. I haven’t seen it so I can’t say anything about it. In all likelihood, the film will be doing some things that this book cannot — and vice versa. Films do their own things — there’s the sound, and there’s the pacing that the viewer cannot control (or rather is not supposed to control; obviously in the day of Netflix and streaming sites that insert advertising that idea has long gone out of the window).

The book brings a viewer closer because it needs to placed into their immediate vicinity — on a lap, a table. It demands more of the viewer because when you close it it’s still there. I’m thinking it’s the still-being-there that would have me prefer the book over the movie (that, again, I haven’t seen — I’m writing these sentiments out of my feelings). I want its intimacy.

In Shiotani, the mundane becomes extraordinary simply because of Edström’s refusal to give in to conventions. If most photobooks are made for a specialist audience, this one really will only appeal to people deeply devoted to them. I don’t see that as a problem, given that this particular book will probably end up in that very small category of truly groundbreaking photobooks. You could place it next to Kikuji Kawada’s Chizu or Lieko Shiga’s Rasen Kaigan. That is this book’s company.

Shiotani is an immersive masterpiece that derives its beauty from its makers’ refusal to work with art photography’s most cherished conventions. Daily life in a small Japanese hamlet becomes extraordinary because every little moment, every little thing is given attention by Anders Edström. As a viewer, you find yourself in the middle of life as it is experienced by a small group of Japanese people. Coming away from the book, you can’t help but look around yourself to wonder whether paying a little more attention might not yield equally unexpected results.

Very highly recommended.

Shiotani; photographs by Anders Edström; texts by Jeff Rian, C.W. Winter; 750 pages; AKPE; 2021