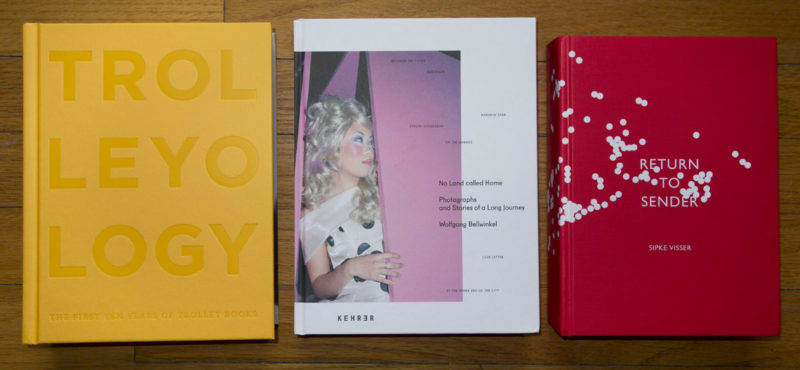

The three books I want to talk about today amount to a total of just under 1,300 pages. That’s not the reason why I decided to review them together, however. Each of these books offers something a little different, something that makes each book not your typical photobook. Seen together, these books could serve as reminders that the medium photobook is complex. There is quite a bit of variation, with many books deviating from being a very specific experience created from that one project of photographs.

Strictly speaking, Trolleyology isn’t a photobook. Instead, it’s a book about ten years of photobooks published by Trolley Books. And it’s about the man behind the publishing house, Gigi Giannuzzi, whose vision created and made Trolley. After Giannuzzi died of pancreatic cancer earlier this year, at way too young an age, in his obituary Sean O’Hagan described him as “a maverick, a radical and a legendary reveller,” noting “you invariably spent the night trying to keep up with him and his appetite for argument, alcohol and provocation” when running into him. That intense passion went into the making of the books shown and discussed in Trolleyology.

You can make a good photobook if you have a moderate amount of passion, but to make a great book you need a lot of passion, ideally a limitless amount.

Trolleyology could have easily become a tedious affair, listing one exciting book after the other. And it does list one exciting book after the other. But it has deftly avoided all tedium, bringing a lot of Giannuzzi’s passion and excitement to the presentation of these many books. For almost every book, you get to read a bit, often quite a bit of an inside story, part of the making of, the creation, the struggles, the fights, and the joy of having all that come together in the end result. There are reproductions of spreads and behind-the-scenes photographs, many of them.

With so many books about photobooks out now, many of them surveys based on countries, Trolleyology shows that you can in fact produce a book around photobooks that adds something new, that offers a different approach to looking at collections of photobooks. After all, photobooks reflect their makers’ visions, and a lot of those get lost when the books are filed away based on geographical or other criteria. There is a reason why the photobook has become such an exciting part of what photography has to offer. Talking more about what drives some of the most creative people to make photobooks can help us learn a bit more about them (and, possibly, ignite our own creative fires).

Wolfgang Bellwinkel‘s No Land Called Home approaches similar ideas, albeit using the perspective of a single photographer. Compiled from photographs shot over the course of 18 years, the book combines personal and assignment/editorial work, mixing it all up to produce one photographer’s view of, well, life. In addition to the photographs, you get segments of very short stories. You end up with something that doesn’t feel whole, something where there are threads that start and end, seemingly without being connected. But taken together, experienced together, there is a very definite story here, 18 years in the life of photographer, traversing the world, rarely staying in the same place for longer.

No Land Called Home is no book you can look at casually. Well, you can, but then you’re basically going to miss almost everything that is unfolding in its pages. Instead, not unlike William Vollmann’s The Atlas (which, curiously, I keep coming back to these days), the bigger picture emerges from the fragments. It’s a very difficult way of making a photobook: You basically have to hope that people will spend enough time with the book and the many pictures and stories, to see the pieces connect. And the pieces do not connect like in a puzzle. Instead, they connect like they tend to do in real life: Often not really fitting, but sticking to each other anyway.

Sipke Visser‘s Return to Sender is a very different beast: “For two and a half years I picked addresses randomly from google maps. I sent to those addresses a handwritten letter like the one on the right here and a photograph I had taken. All in all I sent out 500 letters, all over the United Kingdom and some to the US.” The photographs and resulting correspondences are included in the book. I don’t remember the last time I received a hand-written letter, let alone a letter from a stranger (of course, I’m excluding the automated junk mail that keeps arriving in my mailbox). Who still writes and sends letter? Or are all those people doing that the internet’s “silent majority”?

In any case, Return to Sender reverts the usual process of photobook making. Usually, you take your pictures, put them into a book (ideally with a lot of passion), and then you get your reactions once the book is out in the world. Sending your photographs out first is the exact opposite approach. Needless to say, it’s slightly inaccurate to compare these two approaches. But there is something endearing about reaching out to a stranger and hoping to get something back. Post a photograph on, say, Flickr or Facebook, and you can expect, well… You know what to expect. The difference an actual object makes becomes clear in the book. To see how many people reacted, and how they reacted, is quite amazing, and it could teach us something about our ideas of social interactions (alternatively, it could – should – teach us that the “social” in “social media” comprises just a very limited subset of the meanings included in the word).

Ratings explained here.